Located in modern southern Iraq, the ancient site of Ur (Arabic: Tall el-Muqayyar) grew from a modest agricultural village to one of the most important cities of Mesopotamian civilization. Popularly known as economic and religious center from the fifth millennium to the first millennium BCE.

Although several archaeologists had worked there briefly before him, the excavations of British archaeologist C. Leonard Woolley, between 1922 and 1934, produced the bulk of our knowledge on ancient Ur. Woolley’s deep soundings revealed that a 25-acre city was founded during the Ubaid period (fifth millennium BCE), one of the earliest periods of Mesopotamian urbanism. Following the Ubaid settlement, Woolley encountered a sterile deposit of waterborn sediments he believed was evidence for the Biblical flood story in Genesis 6:9; today, scholars agree that the Euphrates river deposited these sediments during periods of seasonal flooding.

Starting in the fourth millennium, during the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods, a cultic precinct was established that would remain in use throughout Ur’s history. The earliest temple was set on an artificial platform and decorated with colored cones set into the mudbrick walls. Burials associated with the prehistoric periods were excavated both in formal cemeteries and under house floors.

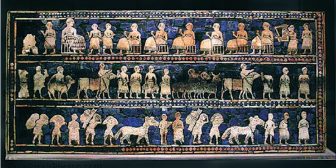

Beginning in the Early Dynastic period (29002350 BCE), Ur became one of several city-states in ancient Sumer whose history is preserved in excavated cuneiform tablets. A new temple was built above the previous temple with planoconvex bricks, a hallmark of early Dynastic building styles. Adjacent to the temple precinct, Woolley excavated what he described as the Royal Cemetery, a necropolis where approximately 2,000 graves were interred between 2600 and 2100 BCE. Lady Puabi was buried in a vaulted chamber within a well-preserved tomb (800), wearing extravagant jewelry of gold and lapis lazuli. Puabi was interred with attendants— musicians, guards, and servants—who apparently drank poison moments before the tomb’s closing. Such instances of mass graves are rare in Mesopotamia, but speak to the power and wealth of Ur’s royal family.

Beginning in the Early Dynastic period (29002350 BCE), Ur became one of several city-states in ancient Sumer whose history is preserved in excavated cuneiform tablets. A new temple was built above the previous temple with planoconvex bricks, a hallmark of early Dynastic building styles. Adjacent to the temple precinct, Woolley excavated what he described as the Royal Cemetery, a necropolis where approximately 2,000 graves were interred between 2600 and 2100 BCE. Lady Puabi was buried in a vaulted chamber within a well-preserved tomb (800), wearing extravagant jewelry of gold and lapis lazuli. Puabi was interred with attendants— musicians, guards, and servants—who apparently drank poison moments before the tomb’s closing. Such instances of mass graves are rare in Mesopotamia, but speak to the power and wealth of Ur’s royal family.

Starting in 2100 BCE, Ur became the capital of a unified Mesopotamian state. During what is known as the century-long Ur III period, the city’s kings added to the preexisting temple precinct, erecting a temple dedicated to Nanna, the moon god and patron of the city, atop an enormous ziggurat. Cuneiform tablets dating to the Ur III period attest to the city’s elaborate bureaucratic practices and its extensive trade relations with societies on either side of the Persian Gulf.

The Ur III period ended when the neighboring Elamites destroyed Ur in 2000 BCE; the city never regained the status it held during the preceding millennium. The city remained occupied despite its decline in importance, and Babylonian and Assyrian kings renovated Ur’s temple precinct from time to time. The city was finally abandoned around 400 BCE.