Variously known as “life crisis” ceremonies, rites of passage, or by the French term rites de passage, this complex of practices includes birthing, coming of age, commencement exercises, marriage, ordination, recruitment into secret societies or military formations, accession to high office, and mortuary processes. In all known human societies, rituals of status transition are highly organized and consume considerable material resources and social energy.

For nearly a century, anthropological approaches to rites of passage have been profoundly influenced by Van Gennep’s classic proto-structuralist model of the “tripartite” structure of these commonly occurring rituals, a formulation that has shown remarkable resilience and longevity in the intellectual history of the discipline. According to Van Gennep, and as famously developed by Victor Turner, such rites commence with the radical separation of the person or persons being transformed, often marked through special adornment, locale, or comportment. The subject then enters into a special interstitial or intermediate state—in Turner’s terms, “betwixt and between” conventional social statuses or categories—in which he or she is neither student nor graduate, child nor adult, unmarried nor married, layman nor priest, heir-apparent nor king. During this “liminal period,” the person undergoing ritual transformation is often subject to special prohibitions and precautions; he or she may be apprehended as especially pure, sacred, stigmatized, or polluted and may be subjected to pain, humiliation, and heightened risks. The person undergoing such a transformative rite is often, in effect, reduced to a subordinate or fluid state subjected to collectively imposed refashioning. This in-between period is often characterized by paradoxical or dramatic reversals of ordinary behavior, often involving real or symbolic violence, exaggerated humor, and carnivalesque elaboration of the lower half of the body; one needs, in effect, to step outside of normal society and socialized frameworks in order to alter one’s social position. In the final stage of reaggregation, during which basic principles of social life are celebrated or reinvigorated, the subject is reintegrated into normal life, usually into a different (often higher-ranked) social role than that occupied before the rite.

Initiation rites, among the most highly elaborated rites of passage, often emphasize the detachment of the initiate from his or her prior links to childhood and exclusively domestic realms by incorporating images of birth and death; they often involve the physical isolation of initiates, often according to principles of strict gender segregation, as well as practices of physical incision, quite literally “cutting” earlier bonds by rupturing the body’s surfaces. Often, initiatory cutting is directed towards the organs of generation (the male foreskin, or, less commonly, the female clitoris or labia), signaling, in part, that sexual pleasure and libidinal drives are henceforth to be subordinated to larger, collectively regulated projects of social and symbolic reproduction. Such rites may, at the manifest level, intensify categorical distinctions between human and animal, as well as male and female, while at other levels blurring or transcending these contrastive schemes.

Initiation rites, among the most highly elaborated rites of passage, often emphasize the detachment of the initiate from his or her prior links to childhood and exclusively domestic realms by incorporating images of birth and death; they often involve the physical isolation of initiates, often according to principles of strict gender segregation, as well as practices of physical incision, quite literally “cutting” earlier bonds by rupturing the body’s surfaces. Often, initiatory cutting is directed towards the organs of generation (the male foreskin, or, less commonly, the female clitoris or labia), signaling, in part, that sexual pleasure and libidinal drives are henceforth to be subordinated to larger, collectively regulated projects of social and symbolic reproduction. Such rites may, at the manifest level, intensify categorical distinctions between human and animal, as well as male and female, while at other levels blurring or transcending these contrastive schemes.

Their tripartite sequence, the extraordinary qualities of the liminal phase, and the bodily symbolism of radical transformation render rites of passage highly appropriate for dramatizing transformations in persons other than the rite’s formal subjects. Those organizing, performing, or attending the ritual often take on certain liminal, interstitial qualities during the ceremony and undergo significant (if subtle or backgrounded) transformations and shifts in status. Rites of passage are thus nearly always collective enterprises that proceed upon multiple tracks, establishing important connections and distinctions among varied persons and groups beyond the proximate, central foci of ritual attention.

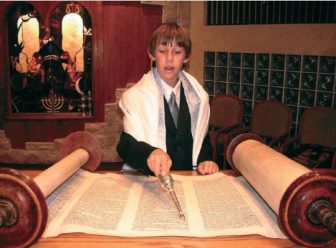

For example, the rites of christening or bris (the Jewish circumcision), while manifestly directed towards transforming the moral and spiritual status of the infant, also confirm or help establish important shifts in other persons’ conditions, especially in the generations of the child’s parents and grandparents. The parents are established in front of the family and the religious community as persons of tradition, substance, and faith. Grandparents from both sides of the family are, if possible, prominent at a christening, and often exhibit considerably warmer, less formal relations with one another than they did at the wedding. At the Jewish bris, the paternal grandfather often holds his grandson as the foreskin is excised, evoking a line of patriarchal authority that in principle stretches back through the generations to the original covenant between the Lord and His chosen people. In this ambiguous liminal position, holding his male flesh and blood under the knife, the grandfather takes on aspects of the early patriarchs themselves, recalling Abraham’s abortive sacrifice of Isaac and Moses’ role as the first circumciser. In this sense, the bris is equally a rite of passage for the grandfather and his grandson, who emerge from it confirmed respectively as patriarch and novice within the family and the wider community; as a reenactment of the mythic forging of the covenant between Yaweh and his chosen people, each bris also celebrates the collective solidarity of the Jewish community.

At the end of the life cycle in modern American society, the funeral orchestrates another set of complex social and temporal relationships. The dead person may be thought of as moving from initial separation (through special treatment, including embalming), into the ambiguous liminal status of funeral corpse, to a final state of integration into the domain of the dead (signified by burial or cremation). This close attention to the dead body not only manages the deceased’s social transition out of the living world, but separates the mourners as a collective social unit out of ordinary life, placing them into an ambiguous interstitial space and time. They wear special somber clothes, adopt a solemn demeanor, and may even be expected to view or kiss the corpse, before the coffin lid is closed and the service begins. At the rite’s conclusion, they are collectively reintegrated into ordinary life, often through actions such as food consumption and lively conversation at a reception, that emphasize the renewal of life.

The ultimate consequence of the funeral’s double tripartite structure is an achieved marked separation between the categories of life and death. Paradoxically, this ritual distance enables subsequent moments of communion between the living and the dead, as in visits to the cemetery, which are often tied to key moments in the annual calendar, such as Christmas, Memorial Day, or Mother’s Day.

In an important reformulation of previous approaches, Terry Turner argues that the intermediate or liminal phase of such rites is characterized not so much by “anti-structure,” as by a kind of hyper-structuration, enabling a kind of regimenting or reconceptualization of the opening and closing phases of the ritual process. The associated cognitive and affective transformations may not necessarily be immediately accessible to the putative subjects of initiation rites (who may primarily experience terror, discomfort, and disorientation during the ceremony itself); indeed, the underlying structural logic of the key transformations may only become apparent to actors later in the life cycle, as they initiate subsequent cohorts or generations.

Precisely because rites of passage have such profound implications for the reproduction of social formations as well as for the refashioning of individual selfhood, these ritual complexes are often subject to intense political struggle and may emerge as arenas through which history is actively made. Nguni state formation in the early 19th century, for example, was predicated on the suppression of circumcision lodges through which local lineages reproduced themselves, in favor of higher-order recruitment into cross-cutting military regiments. Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, a closing oration in an extended mass mortuary process, occasioned the collective reimagining of American democracy, catalyzing and codifying an extended historical transformation that is still being played out to this day. North American society in the early 21st century is gripped by bitter debates over gay marriage, an issue arguably capable of determining the course of national elections. At stake in the organization and evaluation of rites of passage, it would appear, are the constitutive principles upon which human collective life is founded, contested, and potentially remade.

References:

- Turner, V. (1967). Betwixt and between: The liminal period in rites de passage. In The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu ritual (pp. 93-111). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Turner, T. (1977). Transformation, hierarchy and transcendence: A reformulation of Van Gennep’s model of the structure of rites of passage. In S. Moore & B. Myerhoff (Eds.), Secular ritual (pp. 53-70). Amsterdam: Van Gorcum.

- Van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.