Polynesia is a geographical triangle in the Pacific Ocean with Hawaii, New Zealand, and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) as its three points. Starting about 65 million years ago, ongoing volcanic activity began forming the Cook Islands of Polynesia between Fiji and Tahiti. The resultant archipelago consists of 15 major islands, six of which are the worn emergent peaks of now-extinct volcanoes (Mauke, Atiu, Mangaia, Mitiaro, Rarotonga, and Aitutaki); islets, or Hotus; sand-cays on coral reefs; and atolls. Rarotonga is the largest and youngest of those volcanoes forming the Cook Islands. It is located almost 3,000 statute miles directly south of Kauai, the oldest major island of the Hawaiian archipelago. Radiometric dates of lavas indicate that Rarotonga started emerging during the Plio-Pleistocene Age, about 2.8 million years ago. Today, this dormant and eroded volcano has a core surrounded by Pleistocene sands and gravels.

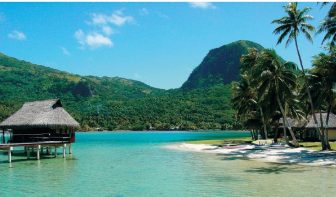

Rarotonga is an elliptical island whose impressive prehistoric-like landscape consists of towering razor-back volcanic ridges of central mountains covered with rich tropical vegetation (sea winds keep Rarotonga cool). This mountainous area is deeply dissected by steep valleys and numerous streams. The rich lowlands are studded with coconut and banana plantations. White beaches stretch along the southern shore of this pristine and peaceful island, but the distant roar of ocean breakers is a constant reminder of both the creative and destructive forces of nature.

One of the geological landmarks of Rarotonga is The Needle (Te Rua Manga), although this unique 300-foot rock outcrop is dwarfed by the higher igneous horizon of this volcanic island landscape. A short, pleasant hike inland along the Avatiu stream, with butterflies and ubiquitous mynah birds as companions, and then a long, strenuous climb up a steep, root-covered mud path will take the adventurous intruder through breathtaking forests of tropical greenery and, finally, to a close-up sight of The Needle in all its primeval splendor.

One of the geological landmarks of Rarotonga is The Needle (Te Rua Manga), although this unique 300-foot rock outcrop is dwarfed by the higher igneous horizon of this volcanic island landscape. A short, pleasant hike inland along the Avatiu stream, with butterflies and ubiquitous mynah birds as companions, and then a long, strenuous climb up a steep, root-covered mud path will take the adventurous intruder through breathtaking forests of tropical greenery and, finally, to a close-up sight of The Needle in all its primeval splendor.

During the past few thousand years, Rarotonga may have welcomed to its shores many brave migrating peoples who came first from the Tongan Islands and then from all over the Pacific Ocean. Not surprisingly, the first discoverers of this island are remembered only through legends and myths.

Centuries ago, seafaring Maori warriors from the islands of Tahiti, Samoa, New Zealand, and elsewhere navigated the ocean on rafts or in outrigger canoes. Using a canopy of stars as their compass, they voyaged throughout Polynesia, eventually discovering the Cook Islands and then the Hawaiian archipelago. No doubt these migrations helped to limit the detrimental kin intermarriages within small communities on these isolated islands.

After waves of early arrivals, the lofty mountains and fertile shores of Rarotonga welcomed their final and definitive visitors from Tahiti during the 13th century. These fierce but cunning Maori warrior clans settled in over 20 tribes, or Iwi, scattered throughout three geographical districts of the island. The Ma-ori of Rarotonga are tall and robust, with black hair, dark eyes, and medium-brown skin. They have a friendly disposition, living close to the land and enjoying music and dance. For hundreds of years, Rarotonga was inhabited only by these nonliterate settlers, who explained their origin and interpreted this world in terms of magic religious beliefs and an oral tradition.

Rarotonga legend has it that in 1350 CE, seven canoes full of Maori warriors from the Takitumu village set sail from the eastern Ngatangiia Harbor for New Zealand. Actually, they would have had to finally depart from the southwest coast at the mouth of the Maungaroa Valley. Their goal, which they achieved, was to colonize New Zealand. This historic site at Takitumu is now marked by seven symbolic stones.

Those ancient inhabitants of Rarotonga spoke a distinct Maori dialect that had evolved out of a prehistoric Eastern Oceanic language. Nevertheless, this dialect linked them to the other cultures of Polynesia. Today, however, this original Maori language is becoming lost to a modern dialect.

Mixing facts with myths and values, Cook Islands legends reflect both the social history and cultural heritage of the early Maori inhabitants. Unfortunately, the oral tradition that preserved these stories is on the decline. To date, only a few of those numerous tales have been recorded for posterity; many such legends may be lost forever.

Nevertheless, one can now read about the evil hag Katikatia, who enticed children into her Rarotonga cave and then ate them; the giant Tamangori of Mangaia, who also loved to eat human beings; those mighty warriors who stole Maru, the highest Rarotongan mountain, and sailed with it back to their flat island of Aitutaki; and the magical origin of the first Polynesian wild hibiscus tree from the grave of the old sage Papa Manu (and, consequently, the discovery of making fire by rubbing together two sticks from this ‘au plant).

The ancient Maori of Rarotonga built an inland road (Ara Metua of Toi) around most of the island so that their dwellings, fields, human burials, and sacred places were protected from hurricanes and cyclones. Even so, periodic famines and frequent intertribal wars threatened their existence.

Maori communities had a sociopolitical hierarchy, with the warrior class positioned just below the royal family but above the common workers and slaves, who were taken prisoner in hand-to-hand warfare. Tribal members practiced exogamy and polygamy while acknowledging patrilineal descent. Land was the property of the tribe. Maori implements were made of stone, bone, or wood. Typical of tools from volcanic islands, adzes made from island basalt were used for cutting wood, for example, in the making of canoes. On Rarotonga, such tools were used more than 1,000 years ago. Weapons were made only of stone or wood, as these people never discovered metallurgy.

Food is of great value to the Maori, who practice terrace farming. As horticulturists, they plant yam, taro, kava, and the sweet potato, or Kumara. They also enjoy an island of beautiful flowering plants: hibiscus, gardenia, bougainvillea, poinsettia, and the mountain orchid. Pigs and fish figure prominently in the Rarotongan diet. Swimmers in the bountiful ocean must beware of stone fish, reef shark, and the deadly cone shell Conus geographus.

The animistic Maori ancestors worshipped many gods. They believed that these gods took temporary residence in material emblems during magico-religious ceremonies, thus demonstrating the significant relationship between their artworks and their beliefs. Furthermore, both gods and human spirits could reside in fish, birds, insects, reptiles, and other life forms. Each god had magical power, or Mana, to adjudicate over particular things.

In this pantheon of spiritual beings, Tangaroa was the supreme god of all creation. As such, he was the lord of plants, fish, fertility, human behavior, and the weather. His image was present throughout most of the Polynesian islands, although in various forms. In fact, his carved statue was even secured to the front of fishing canoes for good luck. Today, the image of Tangaroa appears on the dollar coin of the Cook Islands.

At Rarotonga, both infanticide and cannibalism were customary until the introduction of Christianity in 1823. Revenge in times of war was the major motive for Maori cannibalism. Usually black-tattooed warriors partook of such sacrificial feasts, but the tribal high chief never ate human flesh and workers did so infrequently, for example, during times of famine.

These early Maori believed that after death, a person’s immortal soul, or Wairua, went to reside in Te Reinga, a heaven located under the sea. All brave warriors could look forward to an enviable afterlife in the House of Tiki.

Interestingly enough, explorer James Cook never discovered Rarotonga. In 1789, mutineers from HMS Bounty were the first Europeans known to have seen this island. Twenty-four years later, Captain Theodore Walker merely sighted Rarotonga while sailing from Tahiti to Australia. But the following year, skipper Philip Goodenough went ashore to Avarua. In 1823, with his friend Papehia, the English missionary John Williams from Raiatea brought Christianity to Rarotonga. The Gospel was preached, Maori hymns were composed, churches and schools were built, and the first complete edition of the Holy Bible in Rarotongan Maori reached the island from England in 1852.

Some missionaries used fear, force, and unethical means to convert the Maori to Christianity; they also provoked wars and brought foreign diseases to the island. Nevertheless, most of the Rarotongans quickly replaced Tangaroa with Jesus and were even happy to abandon cannibalism. A former cannibal, the Rarotongan tribal high chief Tepou became one of the earliest converts to Christianity. In a relatively short period of time, Christianity took a firm hold. Today, the Takamoa Theological College at Avarua, founded in 1837, still prepares missionaries for religious work throughout the South Seas.

The coming of Christianity also resulted in the almost total loss of Maori beliefs and customs. The converts burned their wooden idols, discarded their weaponry, and forgot their oral tradition. However, more than 200 different archaeological sites have now been discovered, including over 70 Marae (special gathering places of magico-religious and sociopolitical significance to the early Maori) found on the southern slope of flat-topped Mt. Raemaru, in Maungaroa Valley. These numerous inland sites indicate that a much larger Maori population once existed on this island before the coming of Christianity. Today, Raymond Pirangi (himself a descendant of a tribal high chief, or Ariki) is painstakingly clearing the entrance to the lower Maungaroa Valley so that tourists and scholars may visit its archaeological sites and learn more about the ancient Maori culture.

Along the ancient inner road is the coral and lime palace of Pa, a high chief of the Takitumu tribe. Built above road level, this royal structure indicated the central place of this Maori settlement. The villagers themselves lived in rectangular coconut-palm-thatched houses that kept their occupants both cool and dry. Like early communities, these Takitumu people lived safely inland until the missionaries arrived and built a church on the outer road near the harbor. Only then did the converted natives abandon their own site and move to the coast.

Also of archaeological importance is the Arai-Te-Tonga Marae, which is located inland from Muri Beach and is over 200 years old. This special site of stones designates a place where worshipping Maori held feasts with offerings and rituals for the ancient gods. The largest stone is a basalt pillar from the island of Raiatea, linking the Cook Islands to Tahiti. Likewise, this site functioned as a royal court, or Koutu, where the investiture of a tribal high chief, or Ariki, took place. A community of huts and fields once surrounded this sacred spot. About 10,000 people now inhabit Rarotonga, and its harbor town of Avarua welcomes tourists from all over the world. On Sunday, devout Rarotongans attend Mass or other religious services. Men wear white shirts and ties, while women dress in their finest black-and-white outfits with elaborate straw hats. The religious ceremonies include both thunderous songs of the Maori past and beautiful Christian hymns of today in an intense mixture of two cultures.

References:

- Tara’are, T. A. (2000). History and traditions of Rarotonga (R. Walter & R. Moeka’a, Eds.). Auckland, NZ: Polynesian Society.