The Mbuti Pygmies, referred to as BaMbuti or Bambuti, are an ancient group of hunters and gatherers living deep in the heart of Africa’s Ituri Forest in what is today the Congo. It is speculated that they might be the earliest inhabitants of Africa. Often referred to as the forest people, the Mbuti, whose height rarely exceeds 4 feet 6 inches, have been mystified and romanticized by outsiders since the first written accounts provided by Egyptians around 2500 BC. Some have viewed the Mbuti in a utopian light, noting their egalitarian political and social structure, absence of warfare, sacred rituals, and close-knit social relationships with each other as well as their environment.

African Pygmies

There are a number of pygmy groups throughout Africa, such as the Twa and the Tswa, but it is the Mbuti who form the largest single group of pygmies and have retained their traditional culture for much longer than other pygmy groups. The Mbuti are divided into three primary linguistic-geographical groups—the Efe, the Aka, and the Sua—as a result of adopting the language of those villagers with whom they came into contact. Although there are some marked distinctions among these groups (e.g., some hunt with nets, whereas others hunt with bows and arrows or spears), they nonetheless share many similarities regarding polity, religion, family life, rituals, formalized relationships with villagers, and a current trend toward assimilation with outsiders as globalization encroaches on their previously isolated home.

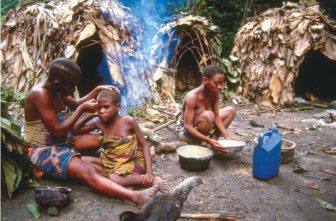

“The Mother and Father”: The Ituri Forest

The Ituri rain forest located in Africa’s Congo lies just north of the equator and covers approximately 70,000 square kilometers (43,496 square miles), an area roughly the size of the state of Wisconsin. It is a world of filtered sunlight under a dense canopy of trees that typically reach 100 feet, with some climbing to 200 feet, leaving the forest shaded, cool, and moist. A single, often impassable dirt road was built during the 1930s and cuts through the forest from east to west, isolating it from much outside influence. To outsiders, the Ituri is a dark and menacing place inhabited with malevolent spirits. Villagers are engaged in an incessant battle with the forest that threatens to overtake their fields. The Mbuti, on the contrary, view the forest as a parental deity deserving love and praise in return for providing them with all they need. For this reason, the Mbuti call themselves bamiki bandura (the children of the forest). The forest provides them with materials for shelter (geodesic dome-shaped huts made of saplings and covered with waterproof mongongo leaves), clothing (cloth made of bark and decorated with plant dyes), and food. The forest is the foundation of the Mbuti culture and shapes elements such as sociopolitical structure, economic production, and religion.

The Band

Hunters and gatherers live in small, mobile, politically autonomous groups known as bands. All members of a band are related to one another either directly or indirectly. Each of the Mbuti bands is dispersed over a large territory with a very low population density. As of 1958, there were only an estimated 40,000 Mbuti in the entire Ituri. The band has a territory that is geographically isolated from other bands and is able to provide sufficient resources for its inhabitants. In addition, fluidity of band membership helps to ensure appropriate band size to prevent outstripping resources while providing the group with enough people to hunt. Band members can move to other bands temporarily or permanently as they see fit. Ties of kin through marriage provide one type of link to other bands. Marriage is exogamous (band members are to marry outside of their own band), and so any individual’s parents will come from two separate bands. Band size is also variable depending on factors such as seasonal variation in game and hunting style. During times of plenty, such as the honey season, Mbuti bands may break into smaller units while hunting is temporarily suspended. In general, band size is larger for net hunters than for bow and spear hunters.

Economic Production and Gender

Although techniques vary, all Mbuti traditionally have met their subsistence needs by hunting and gathering. The Mbuti make use of up to 100 species of plants and more than 200 species of animals, but the bulk of their diet consists of a smaller number of preferred plant and animal species. Women gather and men hunt, but men often gather while on the hunt if they see food that is especially good to eat, and women—especially among the net hunters—are a vital part of a successful hunt.

Among net hunters, men and women participate cooperatively in the hunt using strong nets made of a forest vine (nkusa) that average approximately 1 meter high and 30 to 100 meters long. Men form a large semicircle linking the individual nets, while women close in the other half of the semicircle driving game into the nets. Once an animal is caught in the nets, a man will spear it to death. Because they lack ways in which to store meat over a long period of time, excess meat is traded with villagers for plantation goods, but to hunt too excessively is thought to displease the forest.

Among bow hunters such as the Efe Mbuti, cooperation is also required for a successful hunt, but women do not participate directly in the hunt. Groups that bow or spear hunt do not generally capture as many animals in a hunt but require fewer participants. For this reason, bow and spear hunting bands generally average roughly 6 huts, whereas net hunting requires roughly 15 huts.

Regardless of the way in which a group hunts, securing food requires an average of only 4 hours per day four or five times per week. All meat is shared among the group members, but gathered foods, being more abundant and readily accessible, are kept primarily within the nuclear family.

Other jobs are also divided by gender as well. Men weave and repair hunting nets. Women weave the gathering baskets, cook, and build the family’s hut. However, gender divisions of labor are not strictly maintained. There is no shame in a man cooking, and bachelors often cook for themselves. It has been suggested that women’s contribution to subsistence explains their relatively equal status to men. Women have an equal voice in decision making and control powerful ritual knowledge.

Frequent trade with neighboring villagers may obscure the fact that the Mbuti need only the forest for their subsistence. Beyond a desire for luxury items, they require no outside materials for their survival. In exchange for meat, villagers provide the Mbuti with items such as metal cooking pots and cups, metal spear tips, and plantation foods. Plantation foods, far from being a necessity to the Mbuti, are not as healthy as forest foods. This is especially the case for consumables such as palm wine and tobacco. Even metal spear tips are not essential for a successful hunt and are often replaced by fire-hardened wooden spears.

Frequent trade with neighboring villagers may obscure the fact that the Mbuti need only the forest for their subsistence. Beyond a desire for luxury items, they require no outside materials for their survival. In exchange for meat, villagers provide the Mbuti with items such as metal cooking pots and cups, metal spear tips, and plantation foods. Plantation foods, far from being a necessity to the Mbuti, are not as healthy as forest foods. This is especially the case for consumables such as palm wine and tobacco. Even metal spear tips are not essential for a successful hunt and are often replaced by fire-hardened wooden spears.

Polity

The Mbuti have no chiefs or political leaders to threaten the solidarity of the group. Although knowledge and skills of particular band members may be called on during times of need, there is no formal leader. In that cooperation by all members is essential for survival, group consensus is vital and the only political unit is the band itself. Division of the band into age groups further prevents centralization of power by dispersing responsibilities and decision-making authority. Decisions are made jointly, with the welfare of the band placed over that of any particular individual. The worst crime is to sacrifice the safety or welfare of the group. The ultimate punishment is the threat of ostracism from the band. Social inequalities are prevented in that the Mbuti do not individually own property, material possessions (beyond a hunting net or a particular cooking pot), or other resources.

Birth, Marriage, and Death

Birth for the Mbuti begins much as the rest of life will continue, that is, in a hut made of the forest surrounded by members of the band. A woman generally gives birth in her hut with the assistance of female kin. Sometimes a baby will be sprinkled with juice from vines, which are then tied around the baby’s wrist with a piece of wood from the forest. This helps to make the baby strong in that he or she is part of the forest. All men and women of the generation of the parents will help to raise the child, and all children his or her age will be considered brothers and sisters.

Marriage for the Mbuti is more or less monogamous and begins when a man and woman begin to live in the same hut, eating and sleeping together as a married couple. A man must seal the betrothal by demonstrating his hunting ability to the woman’s parents. However, the marriage will not be official until the birth of the first child, and until that time the marriage may be easily dissolved.

Death is yet another transition for the Mbuti. Life ends in the same style hut and on the same type of sleeping mat into which the individual was born. The men dig a shallow grave in the hut and then collapse the roof on top of the body. There is a period of ritualized grieving where loved ones will mourn loudly, but this ends quickly so as not to offend the forest. The group then moves to a new camp. It is thought that the spirit of the deceased will join the spirits of other deceased Mbuti who live in the forest as they had lived in life, only invisible to those still alive.

Rituals and Religion

Unlike their village neighbors, the Mbuti do not practice witchcraft, sorcery, or magic, but they do have a rich tradition of ritual and religion. There are two central rituals of Mbuti culture: the molimo and the elima. The elima is a formal ritual to mark a young woman’s first menses. This is a time of sexual freedom that may ultimately lead to her selection of a future marriage partner. All of the young women who have recently received their first menses will move to a special elima hut with a group of their close girlfriends. Here they are taught the elima songs as well as aspects of motherhood and sexual relationships. Far from being seen as a time of female pollution, the Mbuti view this as a joyous occasion marking a girl’s transition to womanhood and thus motherhood. Sexual freedom is not, however, without some rules and limitations. The girls go out by day whipping boys as an invitation to the elima hut that evening, where they must fight their way through the girls’ mothers and other older women to gain access to the hut. If a particular suitor is deemed unfit for any reason, he will likely be barred access. It has been speculated that girls practice a natural form of birth control in that there have been no known accounts of pregnancy resulting from the elima ritual. At the end of the ceremony, the girls will take their place in Mbuti society as adult women.

One of the most important rituals for the Mbuti involves awakening and rejoicing the forest to restore order during times of death, prolonged periods of poor hunting, and other crises that threaten the social solidarity of the group. The molimo is both a tube-shaped instrument (capable of making a wide range of sounds) as well as a ceremony. The instrument is kept hidden from women and children and is brought out only at night for the duration of molimo festivals.

The molimo ceremony lasts approximately a month, and everyone cooperates by providing food and fire for the molimo hearth. Vigorous hunting during the day is followed by equally vigorous singing and dancing by the men at night. Men sing and dance throughout the entire night accompanied by the haunting sounds (often in imitation of the leopard) of the molimo trumpet. Dancing reaffirms the age group bonds at the same time that it affirms belief in the continuity of life and the band despite death. Women and children are secluded from the ceremony at night until the end of the ritual, at which time an old woman dances through the molimo fire, scattering it. This is to portray women as both givers and destroyers of life. The men quickly repair the fire. This dance reenacts the time when women originally possessed the molimo before men stole it. Both men and women are, therefore, regarded as central for a productive forest life. Regardless of the purpose for holding a particular molimo, the goal is to restore harmony by awakening and rejoicing the “mother and father” forest.

Contact With the World Outside of the Forest

The Mbuti’s most enduring contact with the world outside of the forest is the relationship with villagers. It might appear that the Mbuti are subservient to villagers in that they are dependent on villagers for plantation foods, metal objects, and even for the substance of their culture. The villagers even refer to themselves as owners of the Mbuti. However, the behavior of the Mbuti when they are in the village mimics that of villagers only superficially and is quickly abandoned once they are in the forest. For example, in the village the Mbuti have a “chief” who negotiates with villagers, but this individual has no authority over the band once the Mbuti are in the forest. The owner of one Mbuti might wish to marry “his” pygmy to a pygmy of another owner to create political and economic alliances. The Mbuti feign acceptance of this marriage solely so that they may enjoy the marriage feast that must be provided by the couple’s “owners.” However, once the Mbuti are back in the forest, the band does not consider the couple to be married.

The Mbuti participate in other village rituals such as the nkumbi (circumcision ceremony). Villagers believe that a boy must be circumcised to become a man and to be able to join the ancestors on death. Villagers involve the Mbuti in this ceremony so that they too will be able to go to the place of the ancestors and thus serve them on death. The Mbuti do not share the beliefs of the villagers, but they participate to gain the villagers’ necessary respect. For the Mbuti, it will be many years after the ceremony before the circumcised boys will be considered as adults. A result of the nkumbi is the bond of brotherhood between an Mbuti boy and a village boy who are paired through the nkumbi ritual. They are expected to trade with each other for life.

Current Trends and the Future of the Mbuti

It is tempting to view the Mbuti as a pristine group of exotic “others” yet untouched by modernity. However, significant contact first began some 300 to 500 years ago as agriculturists moved closer to the Mbuti, bringing new technologies and beliefs. Immigration of agriculturalists was followed by the Arab slave trade and colonialism.

During the colonial period, the Belgian administration enforced an increase in agricultural production of villagers with stiff penalties. Chiefs desperately sought “their” Mbuti to help them with the production. The Belgian government put much pressure on the Mbuti to leave the forest and to resettle as agriculturalists. At this time, the Mbuti remained able to escape into their forest world, but the seeds had been sewn for widespread change.

After the colonial period, the newly independent government of Zaire continued policies of forced resettlement but did so to emancipate the Mbuti, allowing them to contribute to the national economy by farming. They were to be given citizenship and thus subject to taxation. Model villages were constructed to teach Mbuti how to be farmers. Unaccustomed to sedentary life, many became ill and died from contaminated water, nutritional deficiencies, and heat stroke.

By the early 1990s, the effects of globalization were becoming even clearer. The Okapi Faunal Reserve was created to protect the Mbuti and their traditional way of life by, for example, forbidding poaching of animals such as elephants and leopards. Civil wars and the erosion of political control of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, however, made enforcing these laws impossible. The forest has increasingly been cleared for agriculture, logged, and mined for its valuable natural resources such as coltan, a metallic element used in electronics. Such exploitation results in the loss of game and in pollution of the territory. No longer able to hunt and gather, the Mbuti are often compelled to work for cash wages, for the first time introducing sources of material inequality in the band.

The rich cultural traditions and lifestyles of the Mbuti are threatened as their forest foundation is increasingly destroyed. Many Mbuti youths today do not know of the elima, and they hunt excessively for surplus to sell. Previously sacred rituals not to be performed outside of the forest, such as molimo songs, have been brought into the villages. The future of the forest people described more than 3,000 years ago by the Egyptians hangs in the balance as the reach of globalization and modernization continues to expand.

References:

- Duffy, K. (1976). Pygmies of the rain forest. Santa Monica, CA: Pyramid Film & Video.

- Duffy, K. (1984). Children of the forest: Africa’s Mbuti Pygmies. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland.

- Duffy, K. (1986). The Mbuti Pygmies: Past, present, and future. Anthroquest, 34.

- Putnam, A. (1955). Eight years with Congo Pygmies. London: Hutchinson.

- Schebestsa, P. (1933). Among Congo Pygmies. London: Hutchinson.

- Schebesta, P. (1936). My Pygmy and Negro hosts. London: Hutchinson.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1965a). The Mbuti Pygmies: An ethnographic survey. New York: Natural History Press.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1965b). Wayward servants: The two worlds of the African Pygmies. New York: Natural History Press.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1968). The forest people. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Turnbull, C. M. (1983). The Mbuti Pygmies: Change and adaptations. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.