Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Mahatma), who is discussed in the anthropological literature for his adoption of nonviolent resistance (Satyagraha, the vindication of truth by infliction of suffering not on the opponent, but on oneself), which culminated in the “Quit India” movement against the British in Colonial India, is a modern example of the embodiment of classic Weberian charismatic authority. Satyagraha, developed by Gandhi as a way of life, has emerged more popularly as a political tactic, as in civil disobedience movements (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela). Combining spirituality with popular politics based primarily in interventions, Gandhi was able to rapidly ascend to the helm of nationalist politics in British India and by 1919 earned the title of Mahatma (“Great Soul”) from Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali/Indian writer).

Gandhi believed life emerged from a unity of being with no division between the spiritual and the practical. Ahimsa (nonviolence) had clear implications for political conflict, specifically violence used against oppression. Such violence Gandhi believed to be wrong and a mistake that would not end injustice, but rather work to inflame the prejudice and fear that fed oppression.

The genealogy of Gandhi’s political and spiritual thought developed during his years in South Africa (1893-1914), where he was hired as a barrister after his education in England. He drew inspiration from the Bhagavad Gita, the writings of Leo Tolstoy, John Ruskin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau. During his formative years as a sociopolitical activist, he developed concepts and techniques of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance. For Gandhi, Satyagraha emerged as both a creed and tactic and was enacted by declaring opposition to an unjust law, breaking the law, and willingly suffering the consequences.

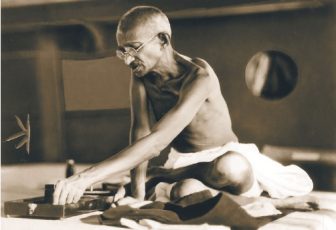

Upon returning to India, Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress, promoting the movement for independence through civil disobedience and fasting. Gandhi’s economic policy promoted the swadeshi movement, the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods, demonstrated by the advocacy for all Indians to wear khadi (homespun cotton cloth). In 1930, he led thousands of people to the sea to collect their own salt rather than pay salt tax (the Salt March).

Upon returning to India, Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress, promoting the movement for independence through civil disobedience and fasting. Gandhi’s economic policy promoted the swadeshi movement, the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods, demonstrated by the advocacy for all Indians to wear khadi (homespun cotton cloth). In 1930, he led thousands of people to the sea to collect their own salt rather than pay salt tax (the Salt March).

Recently, scholars have criticized Gandhian politics and rhetoric in four areas. In South Africa, Gandhi’s essays in the Indian Opinion have been cited as propagating racist colonial discourse. In contemporary India, he is held as an ideal citizen, based on his Hindu values, which create false and separatist ideals of citizenship for India. Critics also point to his economic policies, which, they argue, only helped the rich and made the poor even more disconnected from the larger national project. Gandhi is most heavily criticized for his stance against women. In his autobiographical statements, he talks about his relationship with his wife, which illustrates a view of women that is demoralizing, vilifying, and, ultimately, colonial.

Despite all criticism, M. K. Gandhi is well respected and remembered for the global legacy of his ideas in the disciplines of religion, philosophy and ethics, political science, economics, geography, and anthropology.

References:

- Chatterjee, P. (1993). Nationalist thought and the colonial world: A derivative discourse. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gandhi, M. K. (2001). The story of my experiments with truth: An autobiography (M. Desai, Trans.). Ahmedabad, India: Navajivan. (Original work published 1927).

- Rudolph, S. H., & Rudolph, L. I. (1983). Gandhi, the traditional roots of charisma. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.