Kwakiutl is the name given to the people of one of the tribes of British Columbia who know themselves as the Kwakwaka’wakw, and have five dialects to their Kwak’wala language that stems from the Wakashan phyla. The Kwakiutl are concentrated on the northern end of Vancouver Island, and have constructed a communal lifestyle, for the most part, living on the fringes of the boreal forests. The Kwakiutl developed knowledge of the taking and use of salmon and cedar. From the plentiful cedar, the Kwakiutl made clothes, houses, ceremonial regalia, baskets, storage and serving utensils, canoes for transportation, and totem poles (some of the tallest in the world) carved to display family crests in demonstrations of lineage and status.

The Kwakiutl are best known for their Winter Ceremonials called T’seka, the potlatches where they competed with wealth, and the Hamat’sa, or Cannibal Dancer initiation rituals. When Europeans arrived in the northwest Americas, mercantilism was promoted and consequently affected every part of tribal lifestyle including clothing, food, transportation, hunting and cooking gear, and the symbols of value within the pot-latch. As the ceremonial value or prestige of goods was transformed, the Kwakiutl became infamous for their potlatch wars and related activities. In 1884, the Canadian government enacted a law prohibiting the practice of the potlatch; in 1921, Indian agent William Halliday began arresting potlatch attendants, with sentences to prison for not less than two months. The potlatch artifacts that were confiscated were placed in museums and/or sold. In 1951 the law against the potlatch was removed.

During the generations subjected to “civilization,” some of the culture and the Kwak’wala language fell into disuse.

Lifestyle

Salmon was a food source that not only sustained the villagers through the winter, but also played a role in establishing social technologies that created a people who used salmon and other surplus foods like dried halibut in feasts, coupled with oratory edifying of the known cosmology, which assisted in forming a “moral universe” society. This philosophy both honored and demonstrated a kinship with all life, earthly and supernatural. Much like the Koyukon in Alaska, the Kwakiutl also follow the respectful etiquette of returning the bones of the salmon to the sea after eating, a procedure showing respect to the fish in order to seek favor and to ensure the perpetuation of abundant salmon runs and harvests. In addition to salmon, halibut, and other fish, Kwakiutl subsistence included a variety of berries and crustaceans, supplemented by hunting and digging edible roots. Dried salmon, halibut, and deer were stored in large amounts to ensure survival through the winter, with winter feasting in mind.

The cedar was of inestimable value to the Kwakiutl, as all parts were utilized: bark, roots, wood, and withes. Wood was the base element for shelter, transportation, totemic displays, and bentwood boxes that held valuables such as blankets, masks, and copper shields. Cedar products were made not only for survival, but also as prestige items used in feasts and pot-latches. To obtain the tree that would be best for a long house or canoe required skill in detecting the soundness of a tree; but most important, it required the prayers and intuitiveness to be drawn to the right tree, as the Kwakiutl believed it is the tree that offers itself.

Similar to their northern neighbors, the Haidas and Tlingits, the Kwakiutl were a society of established rank of strict stratification, from the chief at the top, through various ranks from high, middle, and low caste, and then debtors and captured slaves. The complexities of Kwakiutl life included etiquette that was strictly followed, such as the correct procedure of placing food in one’s mouth, how to chew, and other ways to avoid vulgarities. Name, rank, and property were claimed and given during potlatch times. Property consisted of dances, songs, and history of origins; supernatural ancestors; and masks. Feasts could be held for weddings, memorials with a memorial pole, welcoming, naming of children, and for winter ceremonies. Formal invitations and strict protocols were observed at festivities, not the least of which involved refusing an invitation until the fourth time it was extended. In a competitive potlatch, canoes might be burned, copper shields broken or “drowned,” blankets destroyed, and even slaves killed. In Kwakiutl antiquity there were few potlatches given, for these were costly affairs requiring several years to accumulate enough gifts for payments.

European Contact

New prestige items produced through modern European technology made their way through the barter system into the villages, metamorphosing within the Kwakiutl’s spiritual and daily activities. Before Hudson Bay blankets replaced fur pelts in the value system, only the elite could give pelts during a feast due to the special value of the pelt, which was not only the coat of an animal, but also had a spiritual significance representing the power and spirit of the animal. There were strong beliefs throughout the northwest coast tribes that animals also had villages, and without their coat of fur or feathers, they would appear as humans. Fur trade with the Europeans brought the much-coveted “modern” conveniences such as metal, pots and pans, china, clothing, fabric, as well as beads and blankets. Difficult questions had to be answered to adapt the conversion of pelts to the common Hudson Bay blanket, but by the time Boaz met the Kwakiutl in 1886, there was already an established value system surrounding exchange with these blankets of newly bestowed value.

Potlatches captured the imagination of newcomers to the Kwakiutl area, and they became highly controversial among missionaries such as Thomas Crosby, who experienced culture shock in discovering the customs such as dancing. Crosby expressed the horror of witnessing a man cutting himself during a dance, but also explained how a chief felt that a “white man’s dance” of holding another man’s wife while dancing was worse. The barter marriage among the Kwakiutl brought the most criticism from outsiders. Although the marriages for young girls were a sham, existing only to build the status of the girl and ending when the young lady reached her first menses, the practice prompted those such as Reverend Alfred James Hall and his wife to have Girl’s Homes built, where girls could live until they were at least 16 years old. The media’s interest in the potlatch and barter marriages bordered on sensationalism, which brought even more discontent among the settlers and citizens of Canada. Missionaries were given the task to “civilize” the Kwakiutl and other tribes of the northwest.

Ban of the Potlatch

A law prohibiting the potlatch finally passed in 1885, but alterations to this law were necessary for the courts to be able to act on it. Indian agent William Halliday aggressively sought to destroy the potlatch by the indictment and sentencing of its participants, as well as by the confiscation of any potlatch paraphernalia and statements from the accused that they would never potlatch again. In response, people concealed potlatch locations and camouflaged the distribution of gifts and property under the guise of Christmas or other types of gift-giving events, as well as separating the events of dancing and gift giving in order to stay within the law. In 1951, the Canadian Indian Act was revised (sans anti-potlatch laws).

Kwakiutls Today

The Kwakiutl have succeeded in gaining restoration of some of their confiscated treasures and have built two museums to house them: the Kwakiutl Museum and the U’mista Cultural Centre. Since English had become the dominant language, tribes like the Kwakiutl have been attempting to bring their language back.

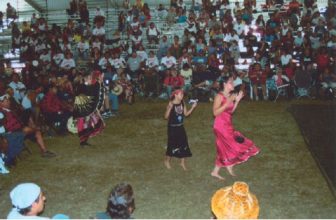

Today the potlatches are not only reestablished, but are even increasing in popularity. New canoes are being carved, not just for artistic enjoyment, but also for use in canoe races at festivals and the new trend of canoe voyages. Today, Kwakiutl canoe teams can be seen training along the coastline, preparing for an annual event inclusive to all northwest coastal tribes that draws pullers (paddlers) from as far as the coast of British Columbia to Washington. Stops are made along the many villages up and down the northwest coast; a different final destination is set each year with a potlatch greeting the pullers when they arrive.

The Kwakiutl have been a historic presence along the northwest coast, with their world-famous pot-latching and Hamat’sa secret societies. Today they are translating that traditional role into a positive, contemporary one by sharing their culture internationally through art, stories, language, and history; thereby instilling pride in their tribe and communities and giving them international prominence.

References:

- Anderson, M. & Halpin, M. (Eds.), (2000). Potlatch at Gitsequkla: William Beynons 1945 field notebooks, Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

- Boaz, F. (1975). Kwakiutl culture as reflected in mythology. Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint.

- Crosby, T. (1907). Among the An-Ko-Me-Nums. In C. Lillard (Ed.), Warriors of the North Pacific (pp. 63-124). Victoria, Canada: Sono Nis Press.

- Dietler, M., & Hayden, B. (Eds.). (2001). Feasts: Archaeological and ethnographic perspectives on food, politics, and power. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Jonaitis, A. (Ed.). (1991). Chiefly feasts: The enduring Kwakiutl potlatch. Seattle: University of Washington Press; New York: American Museum of Natural History.

- McFeat, T. (Ed). (2002). Indians of the North Pacific coast: Studies in selected topics. Seattle: University of Washington Press.