Hominoids are the superfamily to which apes and humans belong. Hominoids are distinguished from cercopithecoids (Old World monkeys), the catarrhine group to which they are most closely related, in having primitive nonbilophodont molars, larger brains, longer arms than legs (except in humans), a broader chest, a shorter and less flexible lower back, and no tail. Many of these specializations relate to a more upright posture in apes, associated with a greater emphasis on forelimb-dominated vertical climbing and suspension.

Hominoids can be classified into two families: the Hylobatidae, which includes gibbons and siamangs, and the Hominidae, which includes the great apes and humans. The gibbons and siamang (Hylobates) are the smallest of the hominoids (with average body weights ranging from 5-11 kg), and for this reason, they are sometimes referred to as the “lesser apes.” The 12 or so species are common throughout the tropical forests of Asia, ranging from southern China to the Indonesian islands. They are remarkable in having the longest arms of any primates, being 30% to 50% longer than their legs. This is related to their highly specialized mode of locomotion, called brachiation, in which they progress below branches using only their forelimbs to swing from support to support. Gibbons are specialist fruit eaters, while the larger siamang incorporates a higher proportion of young leaves in its diet. Hylobatids live in monogamous family groups, in which males and females are similar in size (unlike most catarrhines). Both sexes defend a territory, mainly through complex vocalizations or songs (with male and female pairs of most species producing a duet), which serve to advertise their presence to neighboring pairs. Siamangs have large specialized throat sacs that they inflate during calling. As in Old World monkeys, hylobatids sit upright on branches to sleep, resting on their ischial callosities (i.e., sitting pads on the buttocks), rather than sleeping in nests like great apes.

Hominoids can be classified into two families: the Hylobatidae, which includes gibbons and siamangs, and the Hominidae, which includes the great apes and humans. The gibbons and siamang (Hylobates) are the smallest of the hominoids (with average body weights ranging from 5-11 kg), and for this reason, they are sometimes referred to as the “lesser apes.” The 12 or so species are common throughout the tropical forests of Asia, ranging from southern China to the Indonesian islands. They are remarkable in having the longest arms of any primates, being 30% to 50% longer than their legs. This is related to their highly specialized mode of locomotion, called brachiation, in which they progress below branches using only their forelimbs to swing from support to support. Gibbons are specialist fruit eaters, while the larger siamang incorporates a higher proportion of young leaves in its diet. Hylobatids live in monogamous family groups, in which males and females are similar in size (unlike most catarrhines). Both sexes defend a territory, mainly through complex vocalizations or songs (with male and female pairs of most species producing a duet), which serve to advertise their presence to neighboring pairs. Siamangs have large specialized throat sacs that they inflate during calling. As in Old World monkeys, hylobatids sit upright on branches to sleep, resting on their ischial callosities (i.e., sitting pads on the buttocks), rather than sleeping in nests like great apes.

The great apes include the orangutan (Pongo) from Asia and the gorilla (Gorilla) and chimpanzees (Pan) from Africa. These were formerly included together in their own family, the Pongidae, to distinguish them from humans, who were placed in the Hominidae.

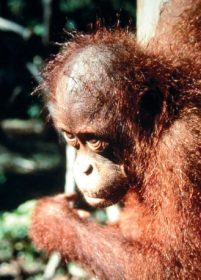

However, recent anatomical, molecular, and behavioral evidence has confirmed that humans are more closely related to the great apes, especially the African apes, and for this reason most scientists now classify them together in a single family, the Hominidae. The orangutan is restricted to the tropical rain forests of Borneo and Sumatra. Traditionally, the Bornean and Sumatran populations, which are morphologically and behaviorally quite distinct, have been separated as subspecies, but there is growing support to recognize them as two separate species, Pongo pygmaeus and P. abelii. They are large (35-80 kg) arboreal primates that climb cautiously through the trees using all four limbs for support. When they descend to the ground, they move quadrupedally, with clenched fists, or bipedally, with the arms raised for better balance. Orangutans subsist mainly on ripe fruits, but they do eat a variety of leaves and small animal prey. Modified sticks are used as simple tools by Sumatran orangutans to extract honey, insects, and seeds as food sources. As is typical of other great apes, they lack ischial callosities and build simple nests to sleep in at night. Adult male orangutans are about twice as heavy as females, and the sides of their faces are adorned with huge fatty flaps. Orangutans are the least sociable of the hominoids and tend to lead solitary lives. Males aggressively defend their territory from other males, which encompasses the ranges of several female consorts. The male long call, a series of reverberating grunts, which can be heard at a distance of 1 km, serves to attract receptive females.

There are two species of chimpanzees, the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and the bonobo or pygmy chimpanzee (Pan paniscus). The common chimpanzee is widely distributed in the forests and

woodlands stretching across equatorial Africa, while the bonobo is restricted to the tropical rain forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Bonobos differ from the more familiar common chimpanzee in having a more slender build, with longer limbs (despite their name, they are not smaller than common chimpanzees); the face is black with pink lips, the hair on top of the head is parted in the middle, breasts are more protuberant in adult females, and they are more adept at walking bipedally. Both species feed and build their nests in trees, but they mostly travel on the ground. Chimpanzees have an eclectic diet of fruits, leaves, insects, and small vertebrates. Common chimpanzees also include meat in their diet, which they obtain by hunting small to medium-sized mammals, especially colobus monkeys. Tool-using behaviors are common, and more than a dozen simple tool types have been identified. Differences in tool use and other behaviors between populations of common chimpanzees have led some researchers to interpret these as cultural traditions. Examples include termite fishing in Tanzania and the use of rocks to crack nuts in West Africa. Chimpanzees are gregarious and sociable, and they live in large multimale-multifemale communities (20-200 individuals), which divide into smaller subgroups (3-15 individuals) for foraging. Common chimpanzees have a hierarchical social structure, in which males maintain their dominance through intimidating displays and overt aggression; they have been known to kill members of other communities. Bonobos are much less aggressive and are able to reduce tension within the group through more intensive use of sexual behavior.

Homo Antecessor

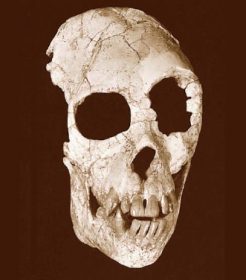

Homo antecessor is the designation given a fossil hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain, defined in 1997 by Bermudez de Castro, Arsuaga, Carbonell, Rosas, Martinez, and Mosquera, in Science magazine. The name antecessor is the Latin word meaning “explorer,” “pioneer,” or “early settler.” Assigning this name, they emphasized that these hominids belong to the first population as yet known in the European continent. The fully modern mid-facial morphology of the fossils antedates other evidence of this feature by about 650,000 years. The midfacial and subnasal morphology of modern humans may be a retention of a juvenile pattern that was not yet present in Homo ergaster. Consequently, Homo antecessor may represent the last common ancestor for Neandertals and modern humans.

Homo antecessor is the designation given a fossil hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain, defined in 1997 by Bermudez de Castro, Arsuaga, Carbonell, Rosas, Martinez, and Mosquera, in Science magazine. The name antecessor is the Latin word meaning “explorer,” “pioneer,” or “early settler.” Assigning this name, they emphasized that these hominids belong to the first population as yet known in the European continent. The fully modern mid-facial morphology of the fossils antedates other evidence of this feature by about 650,000 years. The midfacial and subnasal morphology of modern humans may be a retention of a juvenile pattern that was not yet present in Homo ergaster. Consequently, Homo antecessor may represent the last common ancestor for Neandertals and modern humans.

From 1994 to 1996, nearly 80 human fossil remains were recovered from level six (Aurora stratum) of the Pleistocene cave site of Gran Dolina (TD), Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain. These remains were found in sediments located about 1 m below the Matuyama-Brunhes boundary. In 1997, Bermudez de Castro and his colleagues described the TD6 fossils and defined a new species, which exhibits a unique combination of cranial, mandibular, and dental traits. Midfacial topography shows a modern pattern and infraorbital surface with true canine fossa. The supraorbital torus is double-arched. The superior border of the temporal squama is convex, and there is the presence of a styloid process. The mylohyoid groove extends anteriorly nearly horizontal and courses into the mandibular body, the thickness of which is clearly less than that of H. ergaster and Homo habilis s.s. There is an absence of alveolar prominence at the M1 level.

The extramolar sulcus is narrow. The lateral prominentia is smooth and restricted to the level of M2. The design of the inner aspect of the corpus is similar to that of European Middle Pleistocene fossils. Mandibular incisors are buccolingually expanded with respect to H. habilis s.s., but postcanine teeth are smaller and within the range of H. ergaster, Homo erectus, and Homo heidelbergensis. The maxillary incisors are shovel-shaped. The mandibular canine is mesiodistally short.

The holotype is a fragment of right mandibular body with M1, M2, and M3 (ATD6-5) and an associated set of teeth from the same individual. Holotype and paratypes are provisionally housed in the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain. The final repository of the fossils is the Museo de Burgos, Spain.

References:

- Bermudez de Castro, J. M., Arsuaga, J. L., Carbonell, E., Rosas, A., Martinez, I., & Mosquera, M. (1997). A hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: Possible ancestor to Neandertals and modern humans. Science, 276, 1392-1395.

- Carbonell, E., Bermudez de Castro, J. M., Arsuaga, J. L., Diez, J. C., Rosas, A., Cuenca-Bescös, G., Sala, R., et al. (1995). Lower Pleistocene hominids and artifacts from Atapuerca-TD6 (Spain). Science, 269, 826-830.

- Fernandez-Jalvo, Y., Diez, J. C., Bermudez de Castro, J. M., Carbonell, E., & Arsuaga, J. L. (1996). Evidence of early cannibalism. Science, 271, 277-278.