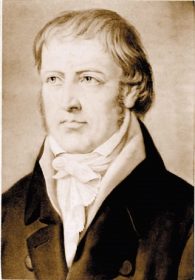

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was born on August 27, 1770, in Stuttgart, Germany, and died on November 18, 1831, in Berlin. He was born into a family of Swabian civil servants. In 1783, his mother, Christine Luise Hegel, nee Fromm (1741), died. After successfully completing his school exams at Gymansium illustre, he started studying at the famous Tuebinger Stift in autumn 1788. He took courses in philosophy, classics, and mathematics, and received an MA in philosophy, which was regarded as equivalent to a doctorate at other universities in 1790. From 1790 to 1793, he studied for and passed a further exam in theology.

Among his friends and fellow students were Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and Friedrich Hölderlin. It has to be noted that Hegel was ponderous and precocious, and he was referred to as “the old man” when he was still a student. Throughout his life, he remained clumsy, and he was a poor public speaker. After successfully finishing his studies in autumn 1793, he started working as a private tutor (Hauslehrer) in Bern, Switzerland, where he remained until 1796. From January 1797 until 1800, he lived as a private tutor in Frankfurt am Main. An inheritance enabled him to give up his post as a tutor, and he moved to Jena in the beginning of 1801, where his friend Schelling as a successor of Fichte lectured in philosophy.

In summer and spring 1801, Hegel wrote a thesis (Habilitation, postdoctoral qualification, necessary condition for lecturing in Germany, connected to the venia legendi) on the orbits of the planets (De orbitis planetarum), which comprises only about 25 pages and which he defended on August 27, 1801. In the same year, he also published his first philosophical work, Differenz des Vichteschen und Schelling sehen Systems der Philosophie. Schelling and Hegel frequently cooperated and edited a philosophical journal (Kritisches Journal der Philosophie), which was, however, discontinued after Schelling left Jena in 1803. In 1805, Hegel was appointed as a sort of associate professor (außerordentlicher Professor) by Goethe, who was the acting secretary of state.

During his time in Jena, Hegel wrote his first main work, Die Phaenomenologie des Geistes (1807), and he also fathered an illegitimate son with his landlady, Christiana Charlotte Burkhardt, nee Fischer (Jena), who before had two children by two other lovers. As a result of financial problems, he gave up his position in Jena and became first the editor of the Bamberger Zeitung (1807), and then the headmaster of a high school in Nuremberg (1808). There, he married Maria Helena Susanne von Tucher, who was 22 years his junior. Together they had two sons. A daughter died shortly after being born, and there were two miscarriages. While Hegel taught in Nuremberg, he wrote Die Wissenschaft der Logik (1812-1816, 2 vols.). In 1816, he accepted the offer to teach at the University of Heidelberg, and while he was there, his work Encyclopaedie der philosophischen Wissenschaften came out (1817). In 1818, he accepted the offer of the chair in philosophy at the University of Berlin, which was formerly occupied by Fichte. His work Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts came out in 1820. He died on November 18, 1831, in Berlin, during a cholera epidemic. The first edition of his complete works was published from 1832 to 1845. Although this edition was very influential, it is not very reliable.

Theory

The three most fundamental realms of Hegel’s philosophy are the realms of logic, nature, and spirit. Even though he distinguishes between nature and spirit, these realms are connected within a monist metaphysics. His understanding of logic is also different from our understanding of logic as it is taught in symbolic logic courses. Logic, according to Hegel, is the science of reason, and reason is both a human as well as an ontological ability, in the same way, as according to Heraclitus, the world is governed by the Logos, and we human beings grasp this by means of our Logos. Within the discipline of logic, Hegel presents his theory of categories. Hegel distinguishes between subjective and objective logic. Objective logic deals with notions such as “being,” “nothingness,” “becoming,” “cause and effect,” “necessity,” and other abstract notions. He bases his analysis on the assumption that to each category, there is another one opposed to it, which upon closer inspection reveals that it is part of the meaning of the original category. Subjective logic, on the other hand, is concerned with the theory of notions, judgments, and inferences. Within his discipline of logic, Hegel also presents his dialectical method, which he himself often refers to as speculative method, which represents a very difficult if not problematic aspect of his philosophy, since one of the premises of this method is that all things are in themselves contradictory. The dialectical movement starts from something, then via the negation of that, something comes to something else, whereby the something else may not be nothing, and via a further negation, or absolute negation, reaches a further beginning. This movement is often described as leading from thesis to antithesis and then synthesis; however, this is not how Hegel described the method. It is one of the tasks of logic to get to know the realms of nature and spirit, as the absolute idea that encloses these two realms is the main topic of logic. As his highest definition, Hegel puts forward the absolute as spirit. However, as the absolute is an all-inclusive process, it as a whole is not only spirit but also nature.

In his philosophy of nature, Hegel is concerned with forces, laws, and types. The realm of the spirit is divided up into the realm of the subjective, objective, and absolute spirit. The subjective spirit comprises anthropology, and psychology, the objective spirit, law, and morality, and the absolute spirit, art, philosophy, and in particular religion. The realm of nature is linked to causality and the realm of spirit to freedom. Nevertheless, according to Hegel, these two opposite realms are united in a monistic metaphysics. It might help to know that his metaphysics bears some similarities to the neoplatonic systems, in which the one, the hen, which is the origin of everything, flows over and brings about nous, the realm of the spirit, and physis, the realm of nature.

In his philosophy of nature, Hegel is concerned with forces, laws, and types. The realm of the spirit is divided up into the realm of the subjective, objective, and absolute spirit. The subjective spirit comprises anthropology, and psychology, the objective spirit, law, and morality, and the absolute spirit, art, philosophy, and in particular religion. The realm of nature is linked to causality and the realm of spirit to freedom. Nevertheless, according to Hegel, these two opposite realms are united in a monistic metaphysics. It might help to know that his metaphysics bears some similarities to the neoplatonic systems, in which the one, the hen, which is the origin of everything, flows over and brings about nous, the realm of the spirit, and physis, the realm of nature.

Hegel applied his basic insights to various topics. He was also concerned with history. In his philosophy of history, Hegel gives an overview of the whole of world history from early civilizations to the French Revolution and his own times. Thereby, he interprets history by means of his own basic concepts as, according to Hegel, everything in history happened for a certain purpose and had a specific meaning and significance: “The history of the world is none other than the progress of the consciousness of freedom.”

“True history,” according to Hegel, begins in early Persia, where the ruler justified his position by reference to a general spiritual principle instead of accepting it just as a natural fact. This represents the beginning of the growth of the consciousness of freedom. When the Persian Empire attempted to expand its realm and defeat the Greek city-states, and the city-states of ancient Greek won, the focus of world history was also passed on. In Ancient Greece, some people, the citizens, were free, whereas in the oriental world, only one, the leader, was free. This shows that the idea of freedom then was still a limited one. In addition, the Greeks and the Orient people lacked the concept of individual conscience, according to Hegel, which was supposed to be the reason why, for example, the Greeks did not distinguish between individual and common interests. Freedom was still incomplete type then.

With Socrates, who took up the command of the Greek God Apollo, “Man, know thyself,” a strong force that went against the order of the Athenian state entered history. Although Socrates was sentenced to death, the principle of individual thinking remained active, and it brought about the downfall of Athens. The Roman world represents the next stage of world history, as it consisted in a collection of many different types of peoples, held together by the absolute power of the state, which represents the natural world. There was a constant tension between the natural world and the individual wills. As a consequence, human beings recognized their own spirituality, and in that way the natural world became less important and the Christian religion came about. Christianity is special because it is based on Jesus Christ, a person who is both a human being and the Son of God. He is supposed to reveal that all human beings participate in God or are made in the image of God. It is not the natural world to which humans belong, but the spiritual. This step represents the negation of the main focus of the natural world. The next step took place in the Germanic world, as there within the Reformation, it was recognized that it is not sufficient to solely concentrate on one’s spiritual life but that it is necessary for living an appropriate religious life, if one adapts the natural world to the needs of free spiritual beings.

The Enlightenment and the French Revolution with their focus on the rights of man are seen as the next and almost last step in the unfolding of freedom. The significance of the French Revolution lies in the fact that it passed on the right principles to other nations—again, Hegel had Germany particularly in mind. The idea of freedom is present only in a state in which both subjective freedom, which consists of the convictions of all the individuals, and objective freedom, which encloses laws and a rationally organized state, are realized and responsible for governing the state. Only then, the history of the world will have reached its goal. Although Hegel does not explicitly say so, it seems that Germany of his own time came pretty close to such a conception.

References:

- Beiser, F. C. (Ed.). (1993). The Cambridge companion to Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hegel, G. W. F. (1979). Phenomenology of spirit (A. V. Miller, Trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor, C. (1977). Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.