The discovery in 1927 near Folsom, New Mexico, of distinctive stone projectile points in unambiguous association with bones of extinct Late Pleistocene bison provided the first widely accepted evidence for a human presence in North America greater than a few thousand years and initiated the field of Paleo-Indian studies in American archaeology. The discovery also inspired the notion that PaleoIndians were specialized big game hunters. The points were named “Folsom points,” and the Folsom point makers were named the “Folsom culture.” Folsom points are one of the most widely recognized point types, possibly in the world, but certainly in North America.

In 1927, in their second season of excavations at the Folsom bison kill site, investigators under the direction of the Colorado Museum of Natural History’s Jesse D. Figgins and Harold J. Cook discovered fluted projectile points embedded in the ribs of a Bison antiquus skeleton. B. antiquus was thought to have gone extinct by the end of the Pleistocene, although the exact age of that event was not known until the 1950s, when radiocarbon dating placed it at about 10,000 years ago. In 1928, Harold Cook used the term “Folsom culture” to refer to the people who made and used the artifacts. By linking technologically distinctive points with extinct fauna in a deeply buried (2-3 m) sedimentary layer, the Folsom site provided a rough base upon which archaeologists could begin building a cultural-historical synthesis of North American prehistory.

The American Museum of Natural History conducted additional excavations at Folsom in 1928 under the direction of vertebrate paleontologist Barnum Brown. After the three seasons of fieldwork, investigators had found remains of about 30 bison, along with at least 14 Folsom points. Discovery of the Folsom site was soon followed by the first excavations of a Folsom bison kill- and camp site near Lindenmeier, Colorado. Here, the Bureau of American Ethnology’s Frank H. H. Roberts excavated remains of 13 B. antiquus, along with hundreds of Folsom points and hundreds of other stone tools, such as scrapers.

The American Museum of Natural History conducted additional excavations at Folsom in 1928 under the direction of vertebrate paleontologist Barnum Brown. After the three seasons of fieldwork, investigators had found remains of about 30 bison, along with at least 14 Folsom points. Discovery of the Folsom site was soon followed by the first excavations of a Folsom bison kill- and camp site near Lindenmeier, Colorado. Here, the Bureau of American Ethnology’s Frank H. H. Roberts excavated remains of 13 B. antiquus, along with hundreds of Folsom points and hundreds of other stone tools, such as scrapers.

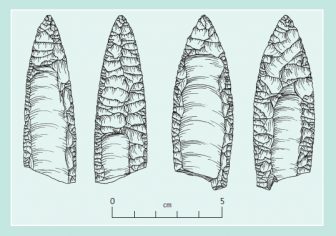

Folsom points (University Museum catalog numbers 36-19-19 and 37-26-13) from Clovis, NM. From Boldurian and Cotter (1999: Figures 38 and 39). Drawings by Sarah Moore. Reproduced with permission of Anthony T. Boldurian and John L. Cotter.

The technology and morphology of Folsom points are very distinctive and are expressed with incredible consistency over a wide geographic area. Folsom points are lanceolate in shape, thin, finished with pressure flaking, very finely made, usually have ground basal and lateral margins, and are distinctive in having a long and proportionally wide channel flake removed from both faces running from the base nearly to the tip, giving them a “fluted” appearance.

Besides the finished points, the fluting process also results in distinctive point preforms and channel flakes; all three are diagnostic artifacts unique to Folsom. Occasionally, a Folsom point is found with only one face fluted. Many Folsom point assemblages, especially near Midland, Texas, also contain unfluted points that are virtually identical to the fluted Folsom points in terms of shape, size, and technology. These points are called “unfluted Folsom points,” or “Midland points,” after the site where they were first documented. Much less common are points made on flakes that were shaped into a roughly symmetrical lanceolate form by minimal unifacial or bifacial marginal retouch. These points have been termed “flake points” or “pseudo-fluted” points.

Besides the finished points, the fluting process also results in distinctive point preforms and channel flakes; all three are diagnostic artifacts unique to Folsom. Occasionally, a Folsom point is found with only one face fluted. Many Folsom point assemblages, especially near Midland, Texas, also contain unfluted points that are virtually identical to the fluted Folsom points in terms of shape, size, and technology. These points are called “unfluted Folsom points,” or “Midland points,” after the site where they were first documented. Much less common are points made on flakes that were shaped into a roughly symmetrical lanceolate form by minimal unifacial or bifacial marginal retouch. These points have been termed “flake points” or “pseudo-fluted” points.

Other flaked-stone tools in Folsom point assemblages include end- and side scrapers, finely pointed gravers, and ultrathin bifacial knives. Rare bone artifacts include eyed needles, beads, and decoratively incised items. Other uncommon artifacts include grinding stones, stone abraders, anvil stones, worked hematite, and even jet beads. Folsom stone tools are made almost exclusively from very high quality raw materials, much of it procured at significant distances. For example, the source of one of the end scrapers at the Lindenmeier site in northern Colorado is approximately 1,000 km to the south in central Texas.

Only a small fraction of Folsom sites have been radiocarbon dated. Uncalibrated radiocarbon dates from nine sites span a 700-year period from 10,980 to 10,250 radiocarbon years before present (rcybp). Calibrated radiocarbon dates from these same sites are older and span a slightly greater time range of 12,950 to 12,000 years before present. When Folsom points are associated with faunal remains, bones of B. antiquus are invariably present. The radiocarbon dates and consistent faunal associations support a Late Pleistocene age for otherwise undated Folsom sites.

Thousands of Folsom points from more than 1,500 sites have been documented. The geographic distribution of Folsom points is primarily on grasslands of the prairie and plains of west-central North America. This distribution reaches from Alberta and Saskatchewan to Chihuahua and southern Texas, and from eastern Oregon and eastern Arizona on the west to Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, western Indiana, and the eastern parts of Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas on the east. Physiographic

provinces included in the Folsom range are the Columbia Plateaus, Northern and Southern Rocky Mountains, Wyoming Basin, Colorado Plateaus, Basin and Range (including eastern Great Basin section), Great Plains, and Central Lowland.

Folsom points (Texas Memorial Museum catalog numbers, clockwise from upper right, 937-18, 937-27, 937-59, 937-28, 937-12) from Clovis, NM. From Sellards (1952: Figures 25). Drawings by Hal Story. Reproduced courtesy of University of Texas Press.

Folsom points (Texas Memorial Museum catalog numbers, clockwise from upper right, 937-18, 937-27, 937-59, 937-28, 937-12) from Clovis, NM. From Sellards (1952: Figures 25). Drawings by Hal Story. Reproduced courtesy of University of Texas Press.

Folsom sites include camps, bison kills and butchery sites, and stone quarry workshops. Sites of all kinds tend to be small in size and in the number of artifacts they contain; Lindenmeier is a notable exception. The numbers of bison represented in kill sites also tend to be small (on the order of 5 to 8), although one site, Lipscomb, in Texas, contained the remains of over 50 bison.

Folsom culture is generally thought to have been characterized by a highly mobile lifestyle necessitated by a reliance on bison for most food, clothing, and shelter needs. Folsom culture is viewed as analogous to highly mobile historic-era Plains Indian cultures that hunted seasonally migratory bison herds. This view is supported by the consistent presence of B. antiquus remains in sites that contain any faunal remains and by typically small sites with artifact assemblages characteristic of a mobile settlement strategy. Some researchers have questioned this view based on several grounds, including the frequent presence of species other than bison (for example, pronghorn, deer, and rabbit) at many Folsom bison kill sites and concerns over potential biases in the archaeological record due to better preservation and visibility of bison bones compared with those of smaller animals. But the existing faunal evidence and the correlation of Folsom site locations with bison habitat appear to support a central role for bison in Folsom subsistence and settlement.

As of the end of 2004, older and younger Paleo-Indian skeletal remains are known, yet none are documented for Folsom. It is generally accepted that Folsom point users descended from earlier Clovis point users.

Other important Folsom sites include Clovis (also known as Blackwater Draw) and Rio Rancho in New Mexico, Mountaineer and Stewart’s Cattle Guard in Colorado, Bobtail Wolf in North Dakota, Shifting Sands in Texas, and Cooper in Oklahoma.

References:

- Amick, D. S. (Ed.). (1999). Folsom lithic technology: Explorations in structure and variation (Archaeological Series No. 12). Ann Arbor, MI: International Monographs in Prehistory.

- Boldurian, A. T., & Cotter, J. L. (1999). Clovis revisited: New perspectives on Paleoindian adaptations from Blackwater Draw, New Mexico. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, University Museum.

- Clark, J. E., & Collins, M. B. (Eds.). (2002). Folsom technology and lifeways (Lithic Technology Special Publication No. 4). Tulsa, OK: University of Tulsa Department of Anthropology.

- Holliday, V. T. (1997). Paleoindian geoarchaeology of the southern high plains. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Wilmsen, E. N., & Roberts, F. H. H. Jr. (1978). Lindenmeier, 1934-1974: Concluding report on investigations (Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology No. 24). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.