The nation of Fiji contains a large group of islands known as an archipelago. Officially titled the Sovereign Democratic Republic of Fiji, the archipelago contains 330 islands that sprawl over 501,800 square miles in the world’s largest ocean, the Pacific. The people of Fiji inhabit about one third of the islands within the archipelago. The two largest islands, Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, and the remaining small islands surround the Koro Sea.

Fiji divides Melanesian and Polynesian islands, with low coral atolls to the east in Polynesia and mountainous volcanic islands to the west in Melanesia. Although the islands of the archipelago form a bridge between the eastern and western South Pacific cultures, Fiji is considered part of the Melanesian Islands. The islands are further divided, in fact, by the International Date Line, which runs across the 180-degree meridian, dividing yesterday from today.

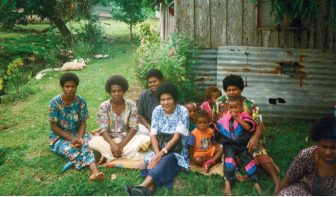

While most people of Fiji are Indian or Fijian, some are Polynesian, European, or Chinese. Migrant communities have maintained their ancestral heritage, religion, customs, and culture. Once feared for their cannibalistic practices, these islanders have been welcomed back into the world community and look forward to a future of economic and social prosperity.

Archeological evidence has shown that peoples first settled in Fiji in the late 2nd millennium BC. A legendary Melanesian chief called Lutunasobasoba led the first settlers, perhaps from Southeast Asia through Indonesia, to Fiji. Melanesian settlers to Fiji were initially fisherman who lived in coastal areas. When they migrated inland, in approximately 500 BC, they developed into agricultural settlements. Population rates and feudalism then increased. In around AD 1000, Polynesians invaded Fiji from Tonga and Samoa, and both cultures would establish a long-term presence in Fiji. The various tribes established a hereditary chief, who was responsible for finding solutions to everyday problems. They enjoyed absolute rule and were considered sacred, not to be touched by ordinary people.

In 1643, a Dutch navigator, Abel Tasman, explored the islands of Vanua Levu and Taveuni. His description of the treacherous Fiji waters kept curious explorers away for almost 150 years. In the 18th century, British explorers would venture close enough to find additional islands that still maintained their mixed Melanesian-Polynesian populations. The Melanesians dominated the windward sides of the islands. The Polynesians controlled the interiors. A complex society with chiefs still existed.

In the early 19th century, trade attracted Europeans. By the 1830s, Fiji was overwhelmed with sailors from Australia, New Zealand, China, and the United States. They sought and most often depleted the island’s supplies of sandalwood and sea cucumbers. This trade gave Fijians access to tobacco, metal tools, clothes, and guns. Early Europeans would teach Fijians enough about firearms to soon enable intertribal warfare that would divide the islands.

In the early 19th century, trade attracted Europeans. By the 1830s, Fiji was overwhelmed with sailors from Australia, New Zealand, China, and the United States. They sought and most often depleted the island’s supplies of sandalwood and sea cucumbers. This trade gave Fijians access to tobacco, metal tools, clothes, and guns. Early Europeans would teach Fijians enough about firearms to soon enable intertribal warfare that would divide the islands.

By the end of the 18th century, Fiji was divided into several small kingdoms, and the Fijian chiefs were noticing more constant tribal warfare. Ratu Ebenexer Ser Cakobau was a notable native Fijian chief, who held a shaky and sometimes disputed title of “King of Fiji.” He supported the messages being spread by the arriving missionaries, and in 1854, he converted to Christianity. Cakobau and the chiefs under his command were becoming increasingly alarmed with tribal division and constant war. He tendered offers ceding the rule of Fiji to Great Britain. In 1874, knowing that only a strong government could restore order and save Fiji, they tendered a second offer to cede the nation, and Great Britain accepted. Since Britain never fought for or conquered the islands, the relationship between Britain and Fiji was always respectful and productive. The British government encouraged a continuance of most Fiji customs and laws.

Although most customs were preserved, missionaries and the British government worked hard to suppress some Fiji practices. Cannibalism was noted from the time Europeans and missionaries first arrived on the shores of Fiji. To the early Europeans, it was a repulsive custom and one of the reasons so many explorers and missionaries stayed clear of the archipelago. The Fijians had practiced it from around AD 500 until the late 19th century. They believed that eating a person destroyed the person’s spirit. Prisoners of war and shipwrecked sailors were brought to the village, sacrificed to the local gods, cooked, and then eaten on behalf of the gods. The custom fell out of practice after years of pressure by the missionaries and British government.

In modern-day Fiji, village land is owned through kinship. When a man dies, his possessions are passed on to his brothers. The brothers then leave this wealth to their eldest sons when they pass. All villagers are expected to contribute to the community or village.

References:

- Lasaqa, I. (1984). The Fijian people: Before and after independence. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- NgCheong-Lum, R. (2000). Fiji. New York: Times Publishing Group.

- Scarr, D. (1984). Fiji: A short history. Laie, Hawaii: Institute for Polynesian Studies, Brigham Young University, Hawaii Campus.