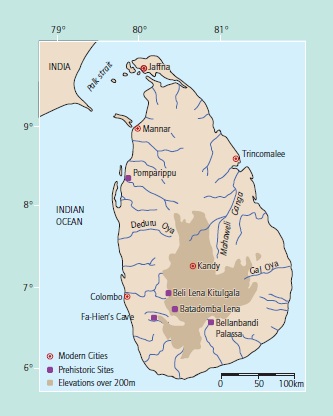

Human skeletal remains of Late Pleistocene antiquity were recovered from several caves and open-air sites in Sri Lanka during the last half of the 20th century. Fa Hien Cave is one of the largest on this island nation and is situated in the southwestern lowland wet zone of Katutara District, Sabaragamuva Province. In 1968, human burials were excavated by Dr. Siran U. Deraniyagala, of the government’s archaeology department, and 20 years later, with his assistant, W. H. Wijepala. These archaeologists dug in two areas at the center and rear of the cave, which yielded at the lowest level above the bedrock numerous stone non-geometric microlithic tools, charcoal from ancient hearths, and faunal and human skeletal remains. Radiocarbon dates obtained from charcoal at this first level and at deposits above it indicate that Fa Hien Cave was occupied over a long period of time: from about 33,000 to 4,750 years ago. This time frame embraces the Late Pleistocene and Early to Middle Holocene epochs. The human bones from all levels were removed from their burial deposits and transported to the Human Biology Laboratory at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, where they were examined by Dr. Kenneth A. R. Kennedy and a graduate student, Joanne L. Zahorsky.

The most ancient skeletal series consists of fragments from several individuals, including a child of 5.5 to 6.5 years of age, two infants, a juvenile, and two adults. Their bones are coated with red and yellow ochre. Cranial and postcranial bones indicate they are secondary burials; that is, following the death of these individuals, their survivors exposed their bodies to the elements. During postmortem decomposition, scavenging animals and climatic temperature changes reduced the bodies to bones. These were later collected and deposited in the graves from which the archaeologists exhumed them. Deposits nearer the present ground surface of the cave floor include skeletal remains of a child and a young adult female dated circa 6,850 and 5,400 years ago, respectively. These, too, are secondary burials, with the bones coated with red and yellow ochre.

Given the fragmentary condition of the cranial and postcranial bones from all of these human remains at Fa Hien Cave, laboratory examination focused upon the teeth, many of which are well preserved. Deciduous and permanent teeth were measured, and their mean crown diameters and robusticity values were compared with a large number of other prehistoric and modern human populations for which dental data have been published. Results of this study show that the dentition reveals relatively large molar tooth size for all specimens, the deciduous molars of infants and children being larger than deciduous molars of later prehistoric populations and modern humans. Since all of the teeth exhibited extreme wear on their occlusal surfaces, it appears that large tooth size was adapted to a coarse diet impregnated with grit and sand from grinding nuts, seeds, and grains in stone querns and other food preparation techniques. A trend toward tooth size reduction in hominids was a consequence of plant and animal domestication that began at the beginning of the Holocene epoch, but Sri Lankan populations continued a hunting-gathering socioeconomic lifeway until the beginning of its Historic period, around the 8th century BC.

Given the fragmentary condition of the cranial and postcranial bones from all of these human remains at Fa Hien Cave, laboratory examination focused upon the teeth, many of which are well preserved. Deciduous and permanent teeth were measured, and their mean crown diameters and robusticity values were compared with a large number of other prehistoric and modern human populations for which dental data have been published. Results of this study show that the dentition reveals relatively large molar tooth size for all specimens, the deciduous molars of infants and children being larger than deciduous molars of later prehistoric populations and modern humans. Since all of the teeth exhibited extreme wear on their occlusal surfaces, it appears that large tooth size was adapted to a coarse diet impregnated with grit and sand from grinding nuts, seeds, and grains in stone querns and other food preparation techniques. A trend toward tooth size reduction in hominids was a consequence of plant and animal domestication that began at the beginning of the Holocene epoch, but Sri Lankan populations continued a hunting-gathering socioeconomic lifeway until the beginning of its Historic period, around the 8th century BC.

Fa Hien Cave is important to archaeologists and human paleontologists because its earliest people were contemporaries with Cro-Magnon populations in Europe and other Late Pleistocene hominids of Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. But Fa Hien Cave is not the only prehistoric site on the island that has been excavated and yielded human skeletal remains.

Geometric microliths with human bones and teeth occur in the same southwestern sector of the island at the cave sites of Batadomba Lena (ca. 28,500 years ago) and Beli Lena Kitulgala (ca. 12,000 years ago), and at the open-air site of Bellanbandi Palassa (ca. 6,000 years ago). Sri Lanka has the earliest-dated microlithic stone tools in the prehistoric record, and on the adjacent Indian mainland, this technology does not appear in archaeological sites until the Early Holocene epoch. These stone tools are first present at about this same time in Europe, although geometric microliths have been recovered from Late Pleistocene sites in sub-Saharan Africa. Later cultural traditions of the Sri Lankan Iron Age flourished by the 7th century BC, with its hallmarks of iron weapons and implements, the construction of megalithic monuments, and unique ceramic vessels. It has been proposed that the aboriginal people of Sri Lanka, the Veddahs, show some cranial and postcranial anatomical similarities to the later microlithic-using inhabitants of the island.

References:

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (1992). The prehistory of Sri Lanka: An ecological perspective (2 vols.). Colombo, Sri Lanka: Department of the Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka.

- Kennedy, K. A. R. (2000). God-apes and fossil men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kennedy, K. A. R., & Deraniyagala, S. U. (1989). Fossil remains of 28,500 year-old hominids from Sri Lanka. Current Anthropology, 30, 394-399.

- Kennedy, K. A. R., & Zahorsky, J. L. (1995). Trends in prehistoric technology and biological adaptations: New evidence from Pleistocene deposits at Fa Hien Cave, Sri Lanka. South Asian Archaeology, 2, 839-853.