Eoliths are chipped flint nodules formerly believed to be the earliest stone tools dating back to the Pliocene (in modern terms, a period dating from 2 million to 5 million years ago). These were regarded as crudely made implements that represented the most primitive stage in the development of stone tool technology prior to the appearance of Paleolithic tools, which show definitive evidence of standardized design and manufacture by humans. Given their crudeness, eoliths were considered barely distinguishable from naturally fractured and eroded flints. This led to heated debates between prehistorians and geologists at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries about whether or not eoliths did indeed represent human artifacts.

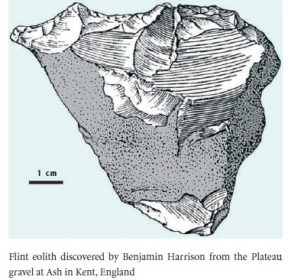

Benjamin Harrison, an amateur archaeologist and naturalist, collected the first eoliths in 1885 while exploring the Chalk Plateau of Kent in southern England (see figure). With the publication in 1891 of Harrison’s discoveries by the eminent scientist Sir Joseph Prestwich, eoliths were widely accepted as the earliest known stone tools. A previous report of primitive stone tools from the Miocene of France by Abbé L. Bourgeois in 1867 had already been discounted. The term eolith (from the Greek eos + lithos, “dawn stone”) was first coined by J. Allen Brown in 1892. Further discoveries of eoliths were made during the early years of the 20th century by J. Reid Moir below the Red Crag of East Anglia, England, and by A. Rutot and H. Klaatsch in continental Europe. The occurrence of eoliths in Western Europe provided confirmation that humans had occupied the region prior to the oldest known fossil finds. This was important evidence that helped contribute to the acceptance of the fossil remains from Piltdown in southern England as early human ancestors. These latter finds were described in 1912 as a new species of extinct human, Eoanthropus dawsoni, but were later found to be a hoax.

Benjamin Harrison, an amateur archaeologist and naturalist, collected the first eoliths in 1885 while exploring the Chalk Plateau of Kent in southern England (see figure). With the publication in 1891 of Harrison’s discoveries by the eminent scientist Sir Joseph Prestwich, eoliths were widely accepted as the earliest known stone tools. A previous report of primitive stone tools from the Miocene of France by Abbé L. Bourgeois in 1867 had already been discounted. The term eolith (from the Greek eos + lithos, “dawn stone”) was first coined by J. Allen Brown in 1892. Further discoveries of eoliths were made during the early years of the 20th century by J. Reid Moir below the Red Crag of East Anglia, England, and by A. Rutot and H. Klaatsch in continental Europe. The occurrence of eoliths in Western Europe provided confirmation that humans had occupied the region prior to the oldest known fossil finds. This was important evidence that helped contribute to the acceptance of the fossil remains from Piltdown in southern England as early human ancestors. These latter finds were described in 1912 as a new species of extinct human, Eoanthropus dawsoni, but were later found to be a hoax.

In 1905, the French archaeologist M. Boule published one of the earliest critiques of the authenticity of eoliths, claiming that it was impossible to distinguish between intentional chipping of flints by humans and damage caused by natural phenomena. This view was substantiated by S. Hazzledine Warren, based on his experiments and observations, which demonstrated that eoliths can be matched exactly by stones chipped as a result of geological processes, such as glacial movements. The debate continued into the 1930s, but support for the artifactual nature of eoliths in Europe waned with the accumulation of a wealth of evidence from geology and archaeology to show that eoliths are consistent with rocks that are naturally fractured, as well as the discovery of undoubted simple stone tools of late Pliocene age in Africa (i.e., Oldowan tools) associated with the earliest members of the genus Homo.

References:

- Klein, R. G. (1999). The human career: Human biological and cultural origins (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Oakley, K. P. (1972). Man the tool-maker. London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History).