Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard was a British social anthropologist known for his ethnographic work among the various tribes of Africa. Evans-Pritchard was born in England in 1902. He studied at the Exeter School, Oxford, and the London School of Economics, under Charles Seligman. In 1945, Evans-Pritchard was appointed reader in anthropology at Cambridge University. In 1946, he was appointed professor of anthropology at Oxford, following the departure of A. R. Radcliffe-Brown. He continued as professor and fellow of All Souls College until his retirement in 1970. The following year, he was knighted.

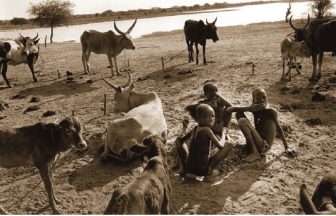

Evans-Pritchard was a significant figure in the development of British social anthropology. First, and foremost, Evans-Pritchard was a brilliant ethnographer, who carried out fieldwork among the Azande and Nuer of the southern Sudan. His field notes contained detailed descriptions of every aspect of life, ranging from religion to political organization to kinship relations. Evans-Pritchard argued that to fully understand another culture, anthropologists must accurately translate and understand the concepts of another unfamiliar culture. This, he argued, was often accomplished by learning another culture’s language and using concepts relevant to that group instead of the anthropologist’s own culture. Many of his ethnographies, including The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People (1940), Kinship and Marriage Among the Nuer (1951), and Nuer Religion (1952), were written with these ideas in mind.

In contrast to other anthropologists, Evans-Pritchard argued that anthropology was not a natural science, but was most closely aligned with humanities. In an article titled “Social Anthropology: Past and Present” (1950), he argued that anthropology is closely related to history due to similarities in theory and method.

During the 1950s and 1960s, much of his research was focused on the study of religion. In Theories of Primitive Religion (1965), he argued against prior notions that religion was constructed for sociological and psychological reasons. Instead, he argued that this idea was biased toward the views of the anthropologist, since quite often they were unable to accurately understand the concepts behind another culture’s motivations. This was most readily demonstrated by his juxtaposing of the religious views of believers and nonbelievers. For a nonbeliever, the cultural beliefs of others are often explained as a result of sociological, psychological, or existential phenomena. These phenomena are often seen as unreal and have limited behavioral consequences.

During the 1950s and 1960s, much of his research was focused on the study of religion. In Theories of Primitive Religion (1965), he argued against prior notions that religion was constructed for sociological and psychological reasons. Instead, he argued that this idea was biased toward the views of the anthropologist, since quite often they were unable to accurately understand the concepts behind another culture’s motivations. This was most readily demonstrated by his juxtaposing of the religious views of believers and nonbelievers. For a nonbeliever, the cultural beliefs of others are often explained as a result of sociological, psychological, or existential phenomena. These phenomena are often seen as unreal and have limited behavioral consequences.

Believers view religion in terms of their reality and the ways in which they should relate or organize their daily activities around these ideas. They generally develop concepts and social institutions that help them to relate these phenomena to reality and deal with the consequences that result from undesirable situations.

Evans-Pritchard continued to work on his ethnographic notes until his death on September 11, 1973. Decades later, his ethnographies remain classic texts that inform us about the non-Western populations of the world.

References:

- Bohannan, P., & Glazer, M. (1988). High points in anthropology. New York: Knopf.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1937). Witchcraft, oracles, and magic among the Azande. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1940). The Nuer: A description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1951). Kinship and marriage among the Nuer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1956). Nuer religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.