The antiquity of humans in the New World had been a controversy during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Insight into just how long ago the incursion of people into the Americas occurred came in 1927, when lanceolate projectile points were found with the remains of extinct bison near Folsom, New Mexico.

Then, in 1932, similar but distinctive stone points were found at Dent, Colorado, this time associated with the mammoth. These artifacts appeared to be related to the Folsom points, both of them bearing axial channels (“flutes”) at their bases for hafting. The Dent points were different, however, in being larger and thicker and having proportionally shorter axial channels and coarser flake scars. Clearly, humans were in North America by at least the late Ice Age.

In the mid-1930s, Dent-type points were found near Clovis, New Mexico, at a site called Blackwater Locality No. 1, beneath an unconformity (a break in the vertical deposition sequence). Above the unconformity were Folsom points. This stratified sequence showed that the Dent-type artifacts (thereafter referred to as “Clovis” points, for the nearby town) were older than the Folsom points. Clovis points, or points closely resembling them, are now known from most of North America. They, and the other artifacts found with them, have come to represent a cultural complex that bears the same name.

Clovis is the oldest clearly defined culture known in North America, with radiocarbon dates concentrating in the range of 11,200-10,900 years BP (before the present) (though a few sites have yielded dates three to four centuries older). Its most characteristic artifact, the Clovis projectile point is lanceolate (axially elongate with roughly parallel sides curving to a point), with a concave base, and one or more elongate axial flakes removed from each side of the base, presumably to facilitate hafting to a shaft. The edges of the lower sides and the base were commonly blunted by grinding, in order to avoid severing the binding. The artifact was made remarkably thin through a process called “overshot flaking” (outre passé), which involved removing a flake from one side of the artifact clear across to the other side. These points, or ones closely resembling them, occur in North America from the East to the West Coast, and from the Canadian plains to central Mexico and possibly even Panama. The Clovis lithic industry is also typified by blades, end scrapers, side scrapers, pièces esquillées, and gravers. Burins, while present, are generally rare, and microblades are absent.

While the Clovis fluted projectile point is distinctive, it does show a degree of variation. This is strikingly illustrated by eight points found at the Naco site in Arizona. They were associated with a mammoth skeleton and are believed to reflect a single hunting event. The points differ markedly in length (approx. 11.6 to 5.8 cm), though less so in width and in the profile of the edges. One of the longest Clovis points known is a 23.3 cm chalcedony artifact from the Richey-Roberts Clovis Cache, at East Wenatchee, Washington State.

Clovis blades, most common in the southeastern United States and the southern Great Plains, are large, triangular in cross section, and thick toward the distal end. No microblades have been found at Clovis sites.

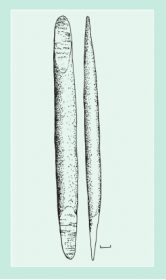

The use of bone, ivory, and antler as raw material for toolmaking was an important aspect of Clovis technology. From these were made what have been interpreted as awls, punches, choppers, scrapers, scoops, fleshers, and points. Osseous rods with beveled, cross-scored ends are known from sites widely distributed throughout the United States. Some of them have been interpreted as foreshafts, short cylinders to which points were bound and that, in turn, were inserted as needed into the socketed end of the main spear shaft. It has also been suggested that these beveled osseous rods served as levers for tightening the ligature of a hafted tool as it was used to slice.

While most Clovis osseous tools appear to be expedient, a clearly formal tool, probably made from mammoth long-bone cortex, appears to have served as a wrench for straightening spear shafts (similar to devices used by Eskimos). It is shaped as a ring with a long, straight handle extending from it. The inner edges of the ring are beveled. A shaft 14 to 17 mm in diameter would be the best fit for the ring, concordant with what would be expected to haft the fluted points found in the area. This artifact, from the Murray Springs site in southeast Arizona, was found with Clovis points near a mammoth skeleton.

Because it was first recognized and characterized in that region, the Clovis complex sensu stricto is best known in the western United States. As researchers move outside this area, however, defining a true Clovis site becomes more difficult. The term has been used informally to include whatever sites have yielded Clovis-like projectile points. As was demonstrated by the eight Naco points, however, there can be variation in the form of points from a single site. On the other hand, points from widely separated localities can be remarkably similar. Also, the very broad geographical distribution of apparent Clovis points spans a wide range of environments and of associated floras and faunas.

The fluted points themselves show stylistic variation that within a given region has been interpreted as reflecting changes over time. In the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada, for example, the Gainey type of point most resembles the western Clovis point, while the Barnes and Crowfield types are thought to be later styles.

Another criterion that may be useful is the presence of Pleistocene megafauna, especially proboscideans (mammoth, mastodon), since the type Clovis occurrence is associated with animals (especially mammoth) that disappeared from that area at the same time that the Clovis complex was replaced by Folsom. In Michigan, the northern limits of early Paleo-Indian fluted points and of fossil proboscideans nearly coincide along an east-west demarcation midway up the Michigan peninsula, the so-called Mason-Quimby Line.

Discoveries at the Hiscock site in western New York, however, show that use of this association for such interpretive purposes requires caution. While Clovis-like Gainey points co-occur here with abundant mastodon bones, some of which were used to make tools whose radiocarbon dates are coeval with Clovis, there is no clear evidence that these people were hunting mastodon. On the other hand, there is evidence that they were retrieving bones found at the site and using them as raw material for toolmaking. Thus, the man-beast relationship may not have been “personal,” and the chronological separation between the people and the megafauna is difficult to gauge.

While there had been a long-standing belief that the Clovis people were the first humans to enter the New World, the last few decades have cast some doubt on this. A scattering of sites in North and South America have yielded radiocarbon dates associated with non-Clovis cultural remains that predate Clovis. Monte Verde, in Chile, contains evidence of human presence somewhere within the range of 12,000-12,500 radiocarbon years ago. Mammoths may have been butchered near Kenosha, Wisconsin, and a tortoise in Florida at around the same time. Radiocarbon dates in cultural contexts, reaching back to 16,000 years BP, have come from the Meadowcroft rockshelter in southwest Pennsylvania. It seems likely that there were humans in the New World some time prior to Clovis, though the paucity of their traces suggests the populations were quite small and scattered.

Clovis Lifeways

Several aspects of Clovis life are reflected by the varied archaeological sites attributed to this culture.

Habitation or campsites were small in comparison with those of the Folsom complex (which succeeded Clovis on the Great Plains). Hearths are represented by depressions less than 3 m in diameter and up to 20 cm deep, containing charcoal. These hearths were not lined with rocks. The presence of well-drained soil and nearby water seem to have been desirable traits for habitations. For example, at the Aubrey site (northeast Texas), a Clovis camp was situated on sandy soil, 1 m above an adjacent pond.

With regard to water, the Hiscock site (western New York) is instructive. This locality featured active springs during the late Pleistocene, and the abundance of bones indicates that animal life here was plentiful. Yet while archaeological artifacts demonstrate the presence of Clovis (or Clovis-contemporary) Paleo-Indians at the site, there is no evidence of significant habitation. This may be due to the fact that Hiscock was a mineral lick, and probably not an appropriate source of drinking water.

There are a few very large, artifact-rich habitation sites that appear to have been occupied repeatedly and/or for extended periods of time (the Gault site in Texas, the Arc site in New York). These are suggestive of places where several bands would come together periodically, a practice that may have been important for the long-term survival of wandering, sparsely distributed human populations.

At sites where prey animals were killed and butchered (or sometimes perhaps scavenged), butchering tools were resharpened on the spot, leaving concentrations of debitage. The Murray Springs site (Arizona) contains a mammoth and a bison kill, along with a hunting camp. A partial mammoth long bone and a tooth found in the camp links it with the mammoth remains. Refitted impact flakes matched with damaged projectile points similarly link the bison kill site with the camp.

Quarry workshops were sources of rock suitable for toolmaking (typically chert), where the raw material was reduced in size and shaped to make it more portable. There were also “bone quarries” (the Hiscock site) where bones, teeth, and antlers were sufficiently abundant to be gathered as raw material for tools.

Clovis people valued chert, obsidian, and other aphanitic rocks that were attractive and of high quality. Many lithic tool collections reflect raw materials obtained from multiple sources within several tens of kilometers of each other, and sometimes from 300 km and even more distant. A point from the Kincaid Shelter site in central Texas was made from obsidian obtained 1,000 km away, in central Mexico. Of course, it is uncertain to what extent the origins of these various rocks reflect mobility of the people and how much is attributable to serial trading. Nevertheless, the frequent occurrence of raw material from distant sources has generally been taken as evidence of a nomadic way of life for the Clovis people.

Concentrations of stone and bone tools, commonly in good condition and sometimes of remarkable aesthetic quality, have been found at several sites (the Richie-Roberts Clovis Cache in Washington State). These have been interpreted as caches, representing either spiritual offerings or emergency stocks left by nomadic people for retrieval in emergencies.

The wide dispersion of their projectile points, and the fact that they are made from chert that was sometimes obtained from distant sources, suggests that the Clovis people were nomadic hunters. When a Clovis site contains animal remains, proboscidean bones are commonly among them, and in the “typical” western Clovis sites (Naco, Dent, Blackwater Locality No. 1, Murray Springs), these belong to mammoths. Clovis people also used mammoth bones to make tools. Hence, the Clovis have been thought of as mammoth hunters.

The exploitation of mastodon on a similar scale by Clovis hunters has been less widely accepted, with only a few sites providing evidence for predation on this species.

Mammoth and mastodon appear to have occupied different habitats (mammoth favoring more open land such as plains and tundra, mastodon being more associated with wooded areas), so it was thought this led to a preference for mammoth hunting. Beginning in the 1980s, however, there have been reported mastodon skeletons in the Great Lakes region in which marks on the bones and peculiarities in the distribution of skeletal elements in peat bogs (former ponds) strongly implies that the animals had been butchered.

Most of the putatively butchered mastodons were young and middle-aged males, animals in the prime of life. Significantly, virtually all of them had died between midautumn and early winter. This nonrandom pattern suggests hunting rather than scavenging. Among modern elephants, males are excluded from the security of the herd around the time when they reach sexual maturity. If this was the case with mastodons (an uncertain proposition, since mastodons were not true elephants, as were mammoths), the pattern suggests that Clovis hunters stalked isolated males as winter approached, knowing that they would have spent the summer and fall storing up fat and other nutrients. Following a successful hunt, they would butcher the carcass and store those parts not used immediately in the bottoms of cold ponds to secure them from scavengers and decomposition. They could be retrieved during the winter for food resources. It has also been suggested that the hunters had filled mastodon intestines with sediment and used them to anchor the meat to the floor of the pond. Mammoth bone piles at Blackwater Locality No. 1 (New Mexico) and Colby (Wyoming) have also been interpreted as winter meat caches. An aggregation of large boulders at the Adkins site (Maine) has been asserted to be a meat cache, though no bones were found associated with it.

It is not clear how a Clovis hunter would have used a spear in a hunt. While spear-throwers (atlatls) dating from the Archaic are known from dry caves in the western United States, none have been found in a Clovis archaeological context. Nevertheless, impact fractures on some Clovis points at the Murray Springs bison kill area indicate sufficient force to suggest they were propelled. Experiments on fresh carcasses from an elephant cull in Zimbabwe demonstrated that a spear tipped by a Clovis point can inflict a lethal wound with the aid of an atlatl. Thrusting with a spear could have done the same, although less reliably. Needle-sharp ivory and bone points, found in Florida underwater sites, may have been useful as lances for reaching the heart. Simple stone tools have proven effective experimentally in performing butchery tasks, and concentrations of chert debitage at kill sites show that stone tools were resharpened and sometimes reshaped during processing.

Most mammoth kills in the West were in low watering places, such as springs, ponds, and creeks. A skilled elephant tracker today can harvest a wealth of information about individual animals and their condition from their trackways, the composition and condition of their dung, and other evidence. It seems reasonable that Clovis hunters would have developed and used similar skills in hunting the proboscideans, which were evidently an important component of their subsistence.

Clovis or early Paleo-Indian hunters seem to have used the local landscape to their advantage. At the Vail Site (Maine) there is a camp and nearby kill and butchery sites. These lie near the narrowing of a river valley, which could have concentrated migrating caribou herds, affording an opportunity for ambush. Similarly, at the end of the Pleistocene, the Hiscock site, in western New York, lay on the edge of a 3-km-wide emergent area that formed a corridor breaching a 153-km-long belt of ponds and wetlands. The site itself was a salt lick and contains abundant bones of mastodon and caribou, as well as early Paleo-Indian tools. This location may have been a reliable area for monitoring the passage of herd animals.

Dogs appear to have been present at late Paleo-Indian localities in the western United States (Folsom component of the Agate Basin site, eastern Wyoming). It seems reasonable, then, that they accompanied Clovis bands, perhaps assisting in their hunts.

Animals other than proboscideans were also hunted by Clovis people. Bison were one of the prey animals at Murray Springs. This site also includes a possible horse kill. Bear and rabbit bones, some of them calcined (burned), occur in hearth areas at the Lehner site (Arizona). Similarly, calcined bones of caribou, hare, and arctic fox were associated with a pit feature at the Eudora site (southern Ontario). Fish bones were found in a hearth at the Shawnee-Minisink site (Pennsylvania).

How large was a Clovis band? The eight Clovis points at the Naco site (Arizona), associated with a single mammoth, are thought to represent one kill or possibly a mammoth that escaped a hunt and succumbed later to its wounds. Four to eight hunters may have been involved in this hunt. If they constituted 20% of their band, then a band size of 20 to 40 people would seem reasonable.

It is assumed that Clovis people traveled primarily by foot. If they had dogs, these animals may have been used, as by later American Indians, to help carry or otherwise transport items, but there is no surviving evidence to support or negate this.

The presence of Paleo-Indian sites on what would have been islands at that time strongly suggests that these people were able to make some sort of water-craft when the need arose. Certainly, some Old World Pleistocene people (Australian aborigines) lived on lands that could have been reached only by boat or raft, so the technology for making watercraft was likely understood by Clovis people.

Little remains to attest to Clovis aesthetic sensibilities. This is rather surprising, as there is a rich artistic legacy in Late Pleistocene archaeological sites of central and eastern Europe, with which the Clovis culture otherwise seems to have a remarkable number of links (see below). Sculptures and cave paintings, as found in Europe, have not been found at Clovis sites. What have been found are simple beads. A roughly cylindrical bone bead was found in the Clovis component of Blackwater Locality No. 1. One from the Hiscock site, in New York, was made from a crudely rounded piece of gray sandstone, about 8.5 mm in diameter and 6 mm thick, pierced by a lumen just under 2 mm wide. This lumen, which must have been produced by a very fine stone spike, was drilled about three quarters of the way through the piece of sandstone, and then finished from the other side to avoid rupturing the bead. Other beads from Paleo-Indian sites are made from bone as well as stone, although not all date from Clovis times. Presumably, these were worn on cords of animal hide or plant fiber.

Other examples of Clovis artistry are inscribed linear designs and patterns on various hard materials. A bevel-based ivory point from an underwater site in the Aucilla River (Florida) has a zig-zag design engraved along its length on one side. A bevel-ended bone rod from the Richey-Roberts Clovis Cache (Washington State) bears a zipperlike series of short, transverse lines along most of its length. While this latter pattern may have been aesthetic or symbolic, it might also have been functional, for example, to prevent a winding cord from slipping along its axis. Several limestone pebbles with complex patterns of inscribed, intersecting lines were found at the Gault site in central Texas.

Clovis people seem to have devoted much of their aesthetic attention to the manufacture of their fluted biface points, some of which are remarkably large and made from attractive stone. In some cases, the stone was obtained from a considerable distance and may have been valued for its appearance.

Religious beliefs of the Clovis people are hinted at by a small number of discoveries. At the Wilsall (Anzick) site in Montana, the crania of two juvenile humans, one of them stained with red ocher (a form of the mineral hematite), were found with ocher-stained Clovis age artifacts. Because the site’s stratigraphy had been extensively disturbed before it could be properly excavated, the relationship of the two crania and the artifacts was uncertain. The stained cranium proved to be 10,500 to 11,000 radiocarbon years old, a reasonable fit with the artifacts. (Later radiocarbon dating showed that the unstained bone was 8,000-9,000 radiocarbon years old, and thus fortuitously associated with the older cranium.) Ocher staining has been found in conjunction with burials at widespread prehistoric sites in the Old World, suggesting that this may have been a burial with artifacts left as an offering.

Evidence of the ritual destruction of lithic artifacts was found in southwestern Ontario, at the Caradoc site. Although the artifacts reflect a Paleo-Indian culture later than Clovis (the estimated age of these items is somewhere between 10,500 and 10,000 radiocarbon years BP), it seems reasonable to hypothesize such behavior among earlier Paleo-Indians. Apparent caches of lithic tools at a number of Clovis sites, especially the one associated with the possible burial at the Anzick site, suggest that these people attributed significance beyond the simply utilitarian to the stone implements they crafted. At Caradoc, at least 71 artifacts had been deliberately smashed. The tools were mostly made of Bayport chert from the Saginaw Bay area of Michigan, about 175 to 200 km from the Caradoc site.

Clovis Origins

Where did the Clovis culture originate? Its roots may lie among Aurignacian and Gravettian hunters, who were in Eastern Europe beginning 24,000 to 26,000 years ago, using mammoth for food and for materials to produce tools, art, and even houses. The environment in which humans interacted with these animals and other megafauna, called the “Mammoth Steppe,” extended into eastern Siberia and picked up again in central North America. A number of archaeological links between the eastern European Upper Paleolithic cultures of the Mammoth Steppe and the Clovis culture have been cited: bifacially flaked projectile points with thinned bases, bevel-based cylindrical bone points, knapped bone, grave goods with red ocher, blades from prismatic cores, end scrapers, unifacial flake tools, bone shaft wrenches, bone polishers, hearths in shallow depressions, and circumferentially chopped and snapped tusks. The percussion bulb was removed from a Murray Springs (Arizona) flake tool by pressure flaking, a common feature in the Old World Late Paleolithic.

At Mal’ta, near Lake Baikal (southeastern Siberia), was found an 18,000-year-old burial of two children with red ocher and cylindrical bone points. Though it is much older, this material is strikingly similar to what was found at the Anzick Clovis site in Montana.

Fig.1 – Bone rod with roughened bevel at one end and point at the other. Bar scale = 1 cm.

Fig.1 – Bone rod with roughened bevel at one end and point at the other. Bar scale = 1 cm.

Most researchers have looked to northeast Asia as the region from which humans first entered the New World and Alaska as the place of their initial arrival. Since much of the earth’s water was transferred from the ocean basins to continental and alpine glaciers during the last glacial maximum, the sea level dropped dramatically. An area of exposed sea floor joined eastern Siberia and Alaska into a vast region called Beringia, whose greatest areal extent existed between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago. The steppe-tundra of Siberia and its fauna expanded into this region and were presumed to be followed by human hunters.

Archaeological evidence shows that people arrived in eastern Beringia (central Alaska) sometime between 12,000 and 11,000 radiocarbon years BP. Once they had occupied this region, however, when did they enter central North America? Until recently, it was thought that the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets of North America separated as early as 25,000 years ago, providing access to the south via an ice-free corridor. More recent evidence, however, indicates that such a corridor did not exist until about 11,000 BP, and that the glacial mass would have blocked inland access from Beringia to the unglaciated southern regions. On the other hand, the presence of land mammal fossils (such as brown bear and caribou) along the northwest coast of North America indicates that this area was ice-free back to at least 12,500 years BP. This has led some researchers to favor a coastal route, using watercraft, for entry into the south.

Two toolmaking traditions have been found at Late Paleolithic sites in Beringia. One is based on wedge-shaped cores and microblades, which are believed to have been set into grooves carved along the sides of elongate pieces of bone or antler to produce sharp-edged projectile points and other tools. This tradition is found in China and northeast Asia, and it reached Alaska and the northwest coast (where it is called the “Denali complex”) by about 12,000 years BP. Microblades, however, have not been found at Clovis sites, and Denali is generally not considered closely related to Clovis.

A second industry that included bifaced projectile points and large flakes struck off of cylindrical cores (the Nenana complex) existed in the central Alaskan region of Beringia around 12,000 to 11,500 years BP. This tradition thus preceded and may have slightly overlapped Clovis, and it has characteristics from which its proponents believe the Clovis tool industry could indeed have been derived.

The Mill Iron site of southeast Montana, a possible Clovis contemporary, contains unfluted, concave-based points. Nenana bifaced projectile points in Alaska are also unfluted. The fluted Clovis point, then, may have developed south of the continental ice sheet in the mid- to late 11,000s BP, rapidly spreading from coast to coast and into Central America. It has been suggested by some researchers that this innovation originated in southeastern North America, where fluted points are unusually abundant and varied, possibly evolving from the Suwanee-Simpson point.

On the other hand, some researchers have pointed to striking similarities between Clovis and the Upper Paleolithic Solutrean and Magdalenian complexes of northern Spain and southern France, which together date to 21,000 to 11,000 years BP. Solutrean points, while unfluted, share other traits with the Clovis form, including the use of overshot flaking. Core blade technology is also similar, and there is even a counterpart to the Murray Springs Clovis shaft wrench. While the European complexes predate Clovis, proponents of a relationship claim that artifacts from putative pre-Clovis North American sites (Meadowcroft in Pennsylvania; Cactus Hill in Virginia) do have Solutrean features.

These researchers envision the first North Americans as having come west across the Atlantic, perhaps along the edge of the North Atlantic ice pack.

The Environmental Context of Clovis

The Clovis culture was contemporary with some of the most dramatic environmental changes—in climate, hydrology, flora, and fauna—since the Sangamon Interglacial. The oldest Clovis dates may coincide with, or slightly predate, the end of the Intra-Allerod Cold Period (IACP), at a time of reversion to the general warming of the Bolling-Allerod Interstadial. This brief warm period (lasting roughly 200 years) brought with it widespread drought in the Western United States and possibly east of the Mississippi River as well. The large proglacial and pluvial lakes that had formed during rapid melting of the ice sheets were greatly reduced in size, and water tables fell. The dryness is reflected in a 140-cm-deep cylindrical well at the Blackwater Draw site (New Mexico) dug during Clovis times. When the water tables finally rose again in the Southwest, the Clovis complex was gone, as was the Pleistocene mammalian megafauna (with the exception of Bison antiquus). This return to wetter conditions is taken to reflect the beginning of the Younger Dryas Cold Period, about 10,900 or 10,800 radiocarbon years ago. The Clovis culture was now replaced by Folsom bison hunters on the Great Plains.

While this scenario may hold for the western states, Clovis sites occurred in such a wide variety of environments that the end of the culture was almost certainly a complex affair, leaving much yet to be learned by archaeologists.

References:

- Boldurian, A. T., & Cotter J. L. (1999). Clovis revisited. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum.

- Collins, M. B. (1999). Clovis blade technology. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Fiedel, S. J. (1999). Older than we thought: Implications of corrected dates for Paleoindians. American Antiquity 64, 95-115.

- Gramly, R. M. (1990). Guide to the Paleo-Indian artifacts of North America. Buffalo, NY: Persimmon Press.

- Haynes, G. (2002). The early settlement of North America: The Clovis era. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Soffer, O., & Praslov, N. D. (1993). From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic-Paleo-Indian adaptations. New York: Plenum Press.