To classify the languages of the world, it is of foremost importance to first decide what constitutes a “language.” Most classification schemata involve spoken languages—alive, endangered, and extinct. The estimated number of spoken languages varies from 3,000 to 10,000, and there are languages spoken by a few societies that are still unidentified. There are some languages that have different names in different cultures, and there are some that have no names. There are languages that are classified as “major” because they are used by numerically large populations of people (for example, English, Polish). There are languages that are used between and among many societies as contact languages besides their individual native or national languages. Sometimes a society will use the term dialect synonymously with language, and sometimes a name is used to refer to a language group as well as to a single language. If one takes into account that some languages have writing systems or can be identified only historically as written forms, and that some languages have sign forms or are strictly sign languages, the method of classification becomes even more complicated.

Families, Branches, and Languages

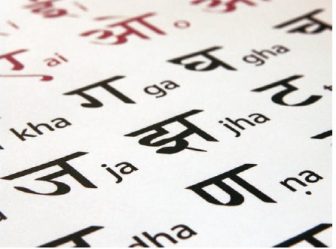

One systematic approach to language classification separates spoken languages into “families” by tracing each language to its possible origin or the geographic place(s) where it was historically documented to have branched off of a parent language. The family system of classification began with philologists theorizing and grouping languages first into the Indo-European family. It is believed that the languages in this group are derived from a parent language, “Proto-Indo-European,” that may have been spoken before 3000 BCE. As indicated in the name, the languages in this family were generated throughout Europe and parts of southern Asia. The Indo-European language family branches off into superordinate categories (for example, Germanic), to subordinate categories (for example, East Germanic, West Germanic, North Germanic), and finally to languages (for example, English, Dutch).

One systematic approach to language classification separates spoken languages into “families” by tracing each language to its possible origin or the geographic place(s) where it was historically documented to have branched off of a parent language. The family system of classification began with philologists theorizing and grouping languages first into the Indo-European family. It is believed that the languages in this group are derived from a parent language, “Proto-Indo-European,” that may have been spoken before 3000 BCE. As indicated in the name, the languages in this family were generated throughout Europe and parts of southern Asia. The Indo-European language family branches off into superordinate categories (for example, Germanic), to subordinate categories (for example, East Germanic, West Germanic, North Germanic), and finally to languages (for example, English, Dutch).

In 1997, David Crystal listed 29 world language families in the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language as well as languages that are termed “isolates” because linguistic analyses of these languages do not show features that are common in any specific schema of the existing families (for example, Basque, Australian Aboriginal).

Criteria for Language Classification

Early philologists and historical linguists of the 18th and 19th centuries explored the similarities and differences between specific target linguistic structures in particular spoken languages and subsequently tried to determine the possible ways in which the languages developed. These early researchers provided a basis for their successors to create language classification systems. The objects of special interest in comparative linguistics are phonology, morphology and words, and syntax.

Purposes for Classification

Scholars have attempted to classify languages with particular purposes in mind. The first purpose is to have a record of all the world’s languages, but there are other reasons for classification. One of these purposes is for the demonstration of cultural and cross-cultural patterns given that native languages and commonly spoken languages have previously been classified linguistically.

In 1997, Philip Parker provided a detailed statistical analysis of more than 460 language groups in 234 countries to illustrate issues connecting linguistic cultures to nine areas of concern (such as economics, cultural resources, demography) with key variables for each area (railways, water, telecommunications). His analyses are especially valuable for the development of nations, especially those designated as Third World countries.

Along a similar vein, scholars have attempted to classify languages according to their use between and among cultures and across nations. Such an endeavor is particularly challenging because there are historic dimensions as well as current cross-cultural variables that need to be characterized in the documentation.

Language Change and Extinction

Another reason for classifying languages is to understand language change, the extinction of languages, and the rebirth of languages. Stephen Wurm and Ian Heyward produced two successive editions of an atlas that identifies world languages that are endangered to greater and lesser degrees as well as those that are at the brink of extinction. At the beginning of the 21st century, researchers around the world consider the situation of language death to be an especially serious one. In Papua New Guinea, for example, there are approximately 820 local languages, and the national language is a Creole, Tok Pisin. Although the government has a positive attitude toward language diversity in New Guinea, by 2001 there were 75 languages in threatening circumstances and 16 extinct languages.

Reasons for concern regarding language extinction include the influence of dominating or dominant languages that cause adaptations to minority languages. In places where trade occurs with major nations of the world, native language speakers may adopt and adapt their own languages to accommodate communication. Currently around the world, there are Creole languages that have become the vernaculars of a number of language communities, and this has been at the expense of previously existing languages.

The Persistence of Spoken Languages

Although there is much concern regarding looking for trends in the endangerment and extinction of languages, there is a hopeful side to classification as well. Certainly, researchers must be pleased when they can take a language off the endangered list or when they can see language growth.

In Togo, a tonal language, Ewe, is one of two indigenous languages that are spoken by more than 4 million people there and in adjoining Ghana. It is a primary language for use in the government, in education, and in mass media. Ewe also has a written form, and there is a body of literature written in Ewe. Togo has a commission to devise Ewe words for technological terms. Felix Ameka recently explained that Ewe is very important for life in West Africa but that the population is in regular contact with English, French, and other indigenous languages in the region. Yet it appears that the people’s efforts to stabilize the identity and use of Ewe are showing results.

References:

- Campbell, G. L. (2000). Compendium of the world’s languages (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Comrie, B. (Ed.). (1990). The world’s major languages. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Crystal, D. (1997). The Cambridge encyclopedia of language (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Davis, J. (1994). Mother tongue: How humans create language. Secaucus, NJ: Carol.

- Garry, J., & Rubino, C. (Eds.). (2001). Facts about the world’s languages. New York: H. W. Wilson.

- Parker, P. M. (1997). Linguistic cultures of the world: A statistical reference. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Wurm, S. A., & Heyward, I. (2001). Atlas of the world’s languages in danger of disappearing (2nd ed.). Paris: UNESCO.