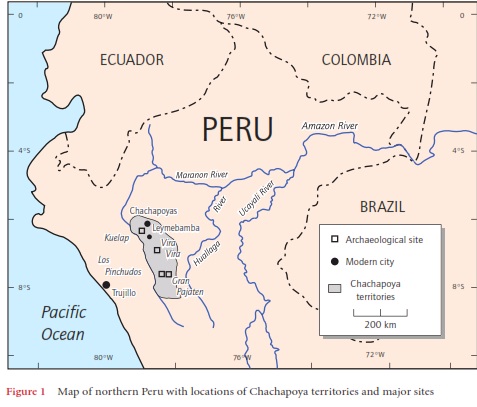

The Chachapoya Indians, often described in popular media as Peru’s ancient “Cloud People,” inhabited the Andean tropical cloud forests between the Maranon and Huallaga River valleys prior to their rapid cultural disintegration after the Spanish conquest in AD 1532 (see Figure 1). In anthropology and in the popular imagination, the Chachapoya represent the quintessential “lost tribe,” founders of a “lost civilization,” and builders of “lost cities” now abandoned and concealed by cold and rainy tropical cloud forests. In world archaeology, the Chachapoya resemble the ancient Maya and Khmer civilizations insofar as they challenge conventional anthropological wisdom regarding theoretical limitations on cultural development in tropical forest environments. The Chachapoya are most widely recognized for their distinctive archaeological remains. These include monumental clusters of circular stone dwellings 4 to 10 m in diameter and built on terraced, and often fortified, mountain- and ridgetops. The most famous include ruined settlements at Kuelap, Vira Vira, and Gran Pajaten, and elaborate cliff tombs like Los Pinchudos, Laguna de los Con-dores, and Revash, set high above mountain valleys. Chachapoya settlements typically yield few surface artifacts, but cliff tombs nestled in arid microclimates afford a rare glimpse of perishable Andean material culture, including preserved mummies, textiles, wooden statues, carved gourds, feathers, cordage, and even Inca string-knot records called quipu.

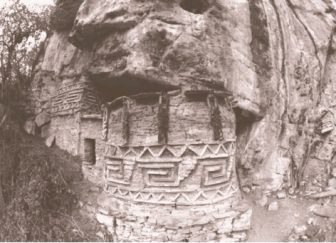

Both scholars and lay authors have attempted to reconcile the paradox of a cosmopolitan, urban, Chachapoya “civilization” seemingly isolated within Peru’s most remote and forbidding eastern Andean cloud forests. The fortified urban complex at Kuelap contains over 400 circular stone constructions sitting atop a 600 m stretch of prominent ridge top that its builders flattened and entirely “encased” with massive masonry walls up to 20 m high (see Figure 2). Buildings ornately decorated with stone mosaic friezes at Gran Pajaten and Los Pinchudos have been granted World Heritage status by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and are widely considered masterpieces of pre-Columbian monumental art (see Figure 3). These contradictions, coupled with the scarcity of historical documentation, have led to much romanticizing, mystification, and pseudoscientific speculation regarding Chachapoya cultural and “racial” origins. Even most scientific theories posit external origins for Chachapoya populations, based on the assumption that tropical montane forests cannot support dense populations and complex social and political structures. Such theories postulate that brief periods of cultural and artistic florescence were externally subsidized by the Inca state. The fall of the Inca is widely believed accountable for the demise of the Chachapoya and other dependent eastern-slope societies, and the rapid abandonment of regions now blanketed in montane forest. Only within recent decades are archaeologists beginning to construct a reliable Chachapoya culture history and to understand the economic and sociopolitical systems that evidently supported autonomous Chachapoya societies.

The name Chachapoya (often written as Chachapoyas or Chacha) is extrinsic, referring to the admin-istrative province established by Inca conquerors around AD 1470, and later described by Spanish chroniclers like Garcilazo de la Vega and Cieza de Leon. Scholars now use the term Chachapoya to refer to the people and Chachapoyas in reference to their pre-Hispanic homeland. The former appears to be an Inca-inspired amalgamation of a local tribal name Chacha with the Inca (Quechua language) term for “cloud,” puya. As such, cultural affiliation implied by Chachapoya is an artifice referring only to local populations grouped together by the Inca on the basis of cultural similarity for the purposes of administration. Archaeological research within the region corresponding to the Inca province reveals broadly shared cultural attributes that evidently reflect the emergence of a regional cultural identity predating the Inca conquest, perhaps by AD 900. Because scholars have been slow to recognize the degree to which cultural and demographic transformations wrought by Inca conquerors permanently altered indigenous social and political structures, they have used the term Chachapoya loosely to refer to pre-Inca, Inca period, and Spanish colonial period cultural identities that are quite difficult to disentangle. Colonial period cultural identities may be the least accessible. By the time of sustained Spanish contact in 1536, the Inca had already exiled large numbers of rebellious Chachapoya, and diseases introduced from the north, west, and east had begun taking a high toll. Chachapoya populations once probably exceeded 300,000 individuals, but by AD 1650, they had declined far in excess of 90%. Demographic collapse, coupled with a lack of sustained Spanish interest in a remote region with no indigenous labor pool, has left scholars with scant historical evidence with which to reconstruct Chachapoya language and culture.

The former appears to be an Inca-inspired amalgamation of a local tribal name Chacha with the Inca (Quechua language) term for “cloud,” puya. As such, cultural affiliation implied by Chachapoya is an artifice referring only to local populations grouped together by the Inca on the basis of cultural similarity for the purposes of administration. Archaeological research within the region corresponding to the Inca province reveals broadly shared cultural attributes that evidently reflect the emergence of a regional cultural identity predating the Inca conquest, perhaps by AD 900. Because scholars have been slow to recognize the degree to which cultural and demographic transformations wrought by Inca conquerors permanently altered indigenous social and political structures, they have used the term Chachapoya loosely to refer to pre-Inca, Inca period, and Spanish colonial period cultural identities that are quite difficult to disentangle. Colonial period cultural identities may be the least accessible. By the time of sustained Spanish contact in 1536, the Inca had already exiled large numbers of rebellious Chachapoya, and diseases introduced from the north, west, and east had begun taking a high toll. Chachapoya populations once probably exceeded 300,000 individuals, but by AD 1650, they had declined far in excess of 90%. Demographic collapse, coupled with a lack of sustained Spanish interest in a remote region with no indigenous labor pool, has left scholars with scant historical evidence with which to reconstruct Chachapoya language and culture.

The scale and magnitude of monumental constructions widely distributed across the northern cloud forest have led some to propose the existence of a unified, pre-Inca Chachapoya state or kingdom. Based upon its extraordinary scale, a few scholars have viewed Kuelap as the paramount Chachapoya political center. The settlement’s population has been estimated at approximately 3,000 prior to the Inca invasion. News media descriptions of Gran Vilaya (La Congona) and Gran Saposoa reported by explorer Gene Savoy as “metropolises” covering 120 and 26 square miles, respectively, are sensational exaggerations, as they con-join distinct sites with no obvious interrelationships. The documentary evidence portrays the Chachapoya as a patchwork of autonomous polities that frequently warred upon one another when not confederated against a common outside threat such as the Inca. Historical evidence further indicates a clear lack of political and even military unity during defensive and insurgent actions against the Inca and factional conflicts between local leaders after Spanish conquest. Because of scant documentary evidence, much of the burden for reconstructing Chachapoya culture has fallen to archaeologists. Inspection of the archaeological record likewise reveals regional variation in architecture, ceramics, and iconography. In terms of settlement design and details of building architecture, no two Chachapoya sites are identical.

The paltry ethnohistorical evidence for Chachapoya culture contained in major colonial period chronicles and scattered administrative and ecclesiastical records offers information of vari-able reliability. Scholars generally view Garcilazo de la Vega’s reproduction of Jesuit priest Blas Valera’s description of Chachapoya culture under Inca domi-nation as reliable. Spanish chroniclers typically describe the Chachapoya romantically as renowned for their fierce warriors and powerful sorcerers. Repeated references to Chachapoya women as “white,” “beautiful,” and “gracefully proportioned” have become fodder for racist theories. The explorer Savoy adds “tall and fair-skinned, with light hair and blue eyes” to buttress his assertion that the Chachapoya reside in mythical Ophir as descendents of Phoenician maritime traders and King Solomon’s miners. Unfortunately, such mis-information regarding Chachapoya origins and racial affiliations disseminated by charlatans and profiteers often sells more copy than scientific treatises, and it abounds on the World Wide Web. By styling themselves in the cinematic molds of Indiana Jones or Allan Quatermain, pseudoarchaeologists such as Savoy have built impressive private fortunes by attracting international media attention to periodic “discoveries” of sites well-known to villagers and archaeologists. Contemporary ethnohistorian Waldemar Espinoza’s more sober interpretation of Chachapoya culture is based upon analysis of some administrative documents, but he presents some conjecture as fact, and he does not reveal all of his sources. Jorge Zavallos, Duccio Bonavia, Federico Kauffman Doig, Arturo Ruiz Estrada, Alfredo Narvaez, Daniel Morales Chocano, Peter Lerche, Inge Schjellerup, Gary Urton, Sonia Guillen, and Adriana von Hagen are among other contemporary historians and anthropologists who have published significant interpretations of Chachapoya society and culture history. Today, archaeologists strive to document Chachapoya settlements and cliff tombs prior to the arrival of highland colonists, uncontrolled adventure-tourists, and looters, which are rapidly destroying the archaeological record. What follows is a brief outline of present scientific knowledge of the so-called Chachapoya distilled from ethnohistory and archaeology.

Location, Environment, and Territory

The Inca province of “Chachapoyas” encompassed approximately 25,000 sq km of mountainous terrain between the Maranon and Huallaga Rivers. This territory trended north and south from the lower Utcubamba river valley near 6° S. latitude, approximately 250 km to the modern boundary separating La Libertad and Huanuco departments at 8° S. latitude. From east to west, it begins in dry thorn forests in the Maranon canyon, near 78° 30′ W. longitude, and straddles moist montane, alpine, and wet montane rain forest ecological zones of the cordillera, to end somewhere in the lower montane rain forests of the Huallaga Valley, near 77° 30′ W. The deep Maranon river canyon provided a natural boundary to the west. The other boundaries, especially the eastern boundary, are much harder to locate precisely. Politically, Inca-period Chachapoyas covers portions of the modern Peruvian departments of Amazonas, San Martin, and La Libertad. Today, populations cluster between 2,500 and 3,000 m, where they produce staple grains, legumes, and tubers on deforested intermontane valley slopes, while periodically tending cattle in higher alpine valleys. Fruit, coca, and chili peppers are cultivated at lower elevations. In pre-Hispanic times, however, Chachapoya populations were much greater and concentrated above 3,000 m on prominent ridgetops along the Maranon-Huallaga divide or between 2,800 and 2,000 m on lower eastern slopes now cloaked in tropical forest.

In general, documentary sources and archaeological evidence still provide scant clues to identify pre-Inca cultural boundaries, which must have shifted frequently with changing social alliances and cultural identities. Enough data are accumulating to begin identifying cultural variability within Chachapoya territory. Documentary sources describe a major Inca and colonial period administrative boundary between northern and southern divisions that shifted between Leymebamba and Cajamarquilla (now modern Bolivar). Archaeologically studied population concentrations and settlement types can be grouped into three imperfectly understood divisions. The first is evident along the Utcubamba-Maranon River divide and throughout the upper Utcubamba watershed. It includes ancient settlements at Kuelap, Caserones (perhaps ancient Papamarca), and Pirka Pirka above Uchucmarca. The second division stretches from Bolivar, southward along the Maranon-Huallaga divide as far as modern Pias, and includes Gran Pajaten and Cunturmarca. Limited exploration of the Huallaga side of the cordillera suggests that this division’s demographic core may have lain on the now forested slopes. An apparently distinctive third division lies between Buldibuyo and Huancaspata, centering around the Parcoy and Cajas River tributaries of the Maranon River, and including the sites of Charcoy and Nunamarca. This third, southernmost area is often excluded from recent considerations of Chachapoya territory, but documentary evidence suggests that it was part of Chachapoyas as the Spanish understood it. Archaeologically, the latter two divisions are the least known. This tripartite grouping may be more apparent than real, as vast stretches of remote and forested terrain remain unknown to science. Even the best-known areas have been inadequately sampled.

The eastern Andean cloud forest habitat of the Chachapoya, often called the “Ceja de Selva” or “Ceja de Montana” (literally edge, or eyebrow, of the jungle), coincides with a major cultural boundary between highland societies participating in Andean cultural traditions and tropical forest lowlanders practicing Amazonian traditions. Geographers regard this sparsely inhabited region as the last forested South American wilderness. Indeed, the cloud forest represents an environmental transition of unparalleled magnitude. Much 20th-century literature depicts an equally rigid cultural dichotomy, split by the eastern “frontier” where Andean civilization ends and the “uncivilized” world of Amazonia begins. However, archaeologists have begun to recognize that the perceived dichotomy between civilized and savage worlds never existed prior to successive imperial conquests by the Inca and Spanish. The Chachapoya and many other poorly known eastern-slope societies left ample evidence of pre-Hispanic settlement in what was thought to be an “empty” wilderness with scattered pockets of highland colonists tending coca fields. Archaeological and ethnohistorical analyses of the so-called Andean frontier now acknowledge the presence of elastic, fluid, and sometimes ephemeral series of social boundaries at this major cultural interface, where interaction was constant. Such boundaries shifted in response to circumstances both local and regional, endogenous and exogenous, as societies in each region offered rare and desirable natural or manufactured commodities to societies in other regions throughout the prehistoric past. A vast amount of archaeological evidence of pre-Hispanic settlement and economic activity is masked today by thick forests, which capitalist ventures repeatedly fail to exploit successfully in any sustainable fashion.

Biological Origins

Biological data from skeletal populations recovered by archaeologists remain paltry but promise to shed light on persistent questions of origins. Preliminary analyses of skeletons from Laguna de los Condores, Laguna Huallabamba, and Los Pinchudos document rather typical Native American physiognomies that may reflect variation within the parameters of Andean populations. Not a shred of evidence supports the notion of “White” Chachapoya populations of European or Mediterranean descent. In fact, studies of DNA from mortuary remains at Laguna Huallabamba linked one cadaver to a living descendent in the nearby village of Utchucmarca, a case demonstrating biological continuity between ancient and modern populations not unlike Britain’s “Cheddar Man.” The problem of origins of the very earliest Andean populations currently remains an issue of contention among archaeologists. Archaeological excavations at Manachaqui Cave in southern Chachapoyas unearthed stone tools and radiocarbon evidence demonstrating human occupation at the edge of the cloud forest by the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, as early as anywhere else in the highland Andes. Although the Manachaqui sequence is not uninterrupted, it yields cultural remains evincing remarkable stylistic continuity through the late pre-Hispanic centuries of Inca imperialism. Of course, cultural continuity does not necessarily reflect biological continuity. Continued biometric research on Chachapoya skeletal samples should address competing hypotheses related to transregional migrations, population interactions, and the antiquity and continuity of human occupation on the eastern slopes of the Central Andes.

Cultural Origins

Anthropology discovered Chachapoyas with the arrival of Adolf Bandolier at the end of the 19th century, while the first scientific archaeology in the region was conducted by Henri and Paula Reichlen during the 1940s. Throughout the 20th century, archaeologists addressed the question of Chachapoya origins, and opinions became divided as they pointed to either highland or lowland sources. Until the mid-1980s, and archaeological fieldwork coordinated by the University of Colorado and Yale University in the United States and Peru’s Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, the notion that the Chachapoya Indians descended from late pre-Hispanic migrants from the neighboring highlands remained the predominant interpretation. Early radiocarbon dates from Gran Pajaten and Manachaqui Cave produced unassailable evidence that humans had occupied the montane cloud forests since 200 BC, and the greater eastern slopes by the end of the Paleo-Indian period. As data accumulate, the archaeology of Chachapoyas has begun to resemble that of other Central Andean regions, but the pre-Hispanic population density, the scale of landscape transformation, and the abundance of monument construction in this extremely wet and steep environment still defy intuition. The extraordinary architectural achievements at monumental sites like Kuelap and Gran Pajaten would garner world attention regardless of their geographical contexts. These characteristics, coupled with isolation from modern Peru’s coast-centered economy, add to the mystique that has nourished pseudoscientific speculation on Chachapoya origins. But it must be borne in mind that the abandonment of this populated region began with early colonial period demographic collapse and forced-relocation programs. It became permanent with the alteration of indigenous social formations and modes of production and the extinction of cultural memories.

The characterization of pre-Inca Chachapoya boundaries previously offered should introduce the reader to the complex problem of identifying the origins of cultural identities such as the Chachapoya. The Chachapoya “culture,” or cultural tradition, was comprised of practices and traditions that converged piecemeal and only crystallized when subjected to particular internal or external forces that remain to be identified. This time of ethnogenesis, when the Chachapoya first appear archaeologically as a regional tradition with shared architectural, ceramic, and mortuary styles, is to some extent an “artifact” of archaeological visibility. Radiocarbon dates suggest that Chachapoya practices of building circular stone dwellings on terraced mountain tops and interring their dead in masonry cliff tombs date to around AD 1000, while more tenuous evidence suggests one or two centuries of additional antiquity. At Manachaqui Cave, the origins of diagnostic Chachapoya-style coarse brown pottery with appliqué decoration and folded rims can be traced all the way back to 1500 BC, when pottery first appears in the Andes.

The ceramic sequence from stratified deposits excavated from Manachaqui shows gaps between 400 BC and 200 BC, and AD 700 and AD 1000, yet basic shapes and decorative norms persist from earliest times to the European conquest. The Chachapoya preference for promontory settlement locations probably dates to centuries between AD 200 and AD 400, when settlement patterns shifted to higher mountain- and ridgetops all along the eastern slopes. The shift likely reflects a new emphasis on camelid pastoralism at higher altitudes, adoption of llama caravan transport technology, and entry into broadened spheres of Andean interregional exchange. Diagnostic Chachapoya architecture, cliff tombs, and iconography still lack radiocarbon evidence to establish a precise developmental chronology. Hence, the full fruition of the complete constellation of cultural attributes that scholars have come to identify as Chachapoyas remains poorly dated. However, it is already clear that Chachapoya “culture” did not simply arrive from elsewhere, but instead developed locally through processes similar to those that governed the development of other, better-known Andean cultures.

Language

The identification of the pre-Inca, indigenous Chachapoya language or dialects would contribute important information to resolve issues of Chachapoya origins. Unfortunately, recognition of these has been obscured by the Inca imposition of Quechua between AD 1470 and AD 1532 as the imperial lingua franca. The demographic collapse of the 16th and 17th centuries further contributed to the virtual extinction of aboriginal languages in the region. Evidently, there was no ecclesiastical interest in recording local languages for indoctrinary purposes, and the only surviving evidence of Chachapoya languages consists of names of individuals and places appearing in historical and modern records and maps. Analysis of these by several specialists has yielded inconclusive results. Most intriguing are recent suggestions of relationships to Jivaroan languages, which are presently spoken in the forested lowlands to the northeast. A distribution overlapping lowland and highland foothill environments would not be unprecedented, since the ethnohistorically documented Palta and Bracamoro of the southeastern Ecuadorian Andes spoke Jivaroan dialects. It is possible, perhaps likely, that several unrelated languages were spoken across pre-Incaic Chachapoyas and that a widely used trade jargon blended elements of these with pre-Incaic north Peruvian highland Quechua and minority language groups like Culle. While this proposal is speculative, it would help account for the extraordinarily murky picture of historical linguistics emerging from the region.

Economy

Documentary sources offer little to suggest that Chachapoya subsistence strategies differed greatly from those of other highland Andean societies. Cieza de Leon’s observation that the Chachapoya kept substantial herds of camelids (llamas and alpacas) may reflect his surprise at finding these ubiquitous Andean herd animals in such extreme environments. Evidently, Chachapoya settlements were located to facilitate access to herds, as well as to fields for cultivating a typical mix of Andean staples, especially high-altitude tubers like potatoes, and maize, legumes, and squash from lower slopes. Remaining at issue is the question of whether the Chachapoya, or at least those “Chachapoya” populations settled deep in the eastern montane forests, were largely self-sufficient with regard to subsistence needs. The vast extent of terracing systems on eastern valley slopes attests to labor organization and agricultural production on a large scale. Although many scholars believe that such terraces were constructed for monocropping of maize and coca under imperial Inca direction, the emerging picture of the Chachapoya would instead suggest a long history of local economic and subsistence autonomy predating Inca hegemony. Of course, no Andean economy was ever entirely self-contained, as all societies relied to some degree upon interregional exchange of items crucial to the maintenance of domestic and political systems.

In the moist soils at Chachapoya archaeological sites, food remains do not ordinarily preserve well, but recovered samples of charred potatoes, maize, and beans support documentary evidence. Studies of floral and faunal remains from the subalpine rockshelter Manachaqui Cave (3,650 m), coupled with paleoecological data from sediment cores recovered at nearby Laguna Manachaqui, suggest that local populations intensified the cultivation of high-altitude grains, like quinoa, by 2000 BC. Remains of maize and beans likely cultivated at lower altitudes appear around 800 BC, and camelids enter Manachaqui’s archaeological record between AD 200 and AD 400. With the exception of the relatively late introduction of llamas and alpacas, these data exhibit a developmental sequence resembling those recovered from other Central Andean regions. Evidently, local populations did not adopt domesticated camelids as sources of meat and wool, as did Andean populations in neighboring regions. Instead, the appearance of camelids correlates with other evidence suggesting utilization of llamas as beasts of burden in broadening networks of Andean interaction.

Economic activities that lie at the heart of Chachapoya cultural development relate to the geo-graphically privileged location of these societies. Poised strategically between populations that anthropologists typically dichotomize as “Andean” and “Amazonian,” the Chachapoya supplied a crucial link in long chains of interregional communication and exchange. Because of its unusually deep penetration into the Central Andes, archaeologists have long believed that the Upper Maranon River valley west of Chachapoyas served as a major “highway” for migrations and trade throughout Andean prehistory. However, the role of the upper Maranon may be overrated, as its canyon is narrow and steep and the river is only seasonally navigable by balsa rafts through the canyon above the mouth of the Utcubamba River. By land, entry to the Central Andes from the northeastern lowlands can be gained only by traversing the populated ridgetops of Chachapoyas. By river, greater penetration of the Central Andes could be gained by canoe navigation up the Huallabamba River into the heart of Chachapoyas or by navigating the southward course of the Huallaga River as far as Tingo Maria in Huanuco Department. The latter route bypasses Chachapoyas, but also bypasses most of northern Peru. Scattered references to paved roads and Inca outposts in the forested Huallabamba valley further indicate that this was a major gateway to the Central Andes. During the mid-16th and 17th centuries, Chachapoyas was the jumping-off point for expeditions to Amazonia in search of mythical El Dorado. Ethnohistorical analyses describe the lowland Cholones and Hivitos Indians as trade partners living along the middle Huallaga. Products typically traded across the eastern slope would include feathers, wax, honey, stone and metal axes, coca, cotton, wool, vegetal dyes, hardwoods, slaves, medicinal herbs, and a host of products that do not ordinarily preserve in archaeological sites.

Although the Chachapoya are renowned as inhabitants of a remote and isolated region, the archaeological record attests to intensive interaction through extensive exchange networks stretching toward all points of the compass at one time or another. Evidence of long-distance interaction is evident in projectile point and pottery styles shared across considerable distances from earliest times. Studies at Manachaqui Cave reveal that exchange relations with populations to the north and east were particularly important prior to AD 200, when Chachapoya populations intensified their trade relationships with Central Andean societies in Cajamarca, Huamachuco, and the Callejon de Conchucos. Cajamarca trade ware and small amounts of Huari pottery attest to uninterrupted participation in Central Andean exchange networks through Inca times, when even coastal Chimu pottery finds its way into Chachapoya tomb assemblages. However, it was the trade linkages with lowland neighbors in the Huallaga Basin that the Inca coveted to the extent that they conquered, and reconquered, the Chachapoya at great expense. Extensive Inca constructions at sites like Cochabamba and Cuntur Marca reflect the importance of these localities as major entryways to the eastern lowlands. Chachapoyas is remote only to the degree it is isolated from Peru’s national infrastructure. The archaeological evidence demonstrates that Chachapoya societies occupied an enviable position at one of South America’s most important pre-Hispanic crossroads.

Sociopolitical Organization

Very little is known with certainty regarding indigenous Chachapoya sociopolitical organization, and especially the basis for “Chachapoya” cultural identity prior to Inca conquest. Documentary evidence attests to unification of autonomous, small-scale polities with the imposition of Inca authority and its attendant political, economic, and religious infrastructure. In the context of empire, the Chachapoya amounted to an ethnic group, which, like other such Andean groups, was recognized by particular clothing and headwear. Current interpretations depict pre-Incaic Chachapoyas as a patchwork of “chiefdoms,” or curacazcos in Andeanist parlance, led by local chiefs, or curacas. These, in turn, were based upon Andean kin-based corporate groups called allyus specific to certain settlements, or local clusters of settlements. The small circular dwellings typical of the Chachapoya suggest nuclear family habitations and bilateral descent. Virilocal residence patterns have been suggested. Espinoza’s use of the medieval Spanish term behetias to describe Chachapoya polities may seem inappropriate as a concept borrowed from the Old World. However, it may be more accurate than “chiefdom” in characterizing political systems in which leadership status could be achieved as well as ascribed. Some pre-Inca Chachapoya polities may have indeed been “rank societies,” conforming to the classic “chiefdom” model. However, a graded series of leadership statuses, including the kind of ad hoc and situational varieties described by Espinoza, likely characterized some Chachapoya communities. Archaeological evidence should speak to this problem, but neither chiefdomlike site hierarchies nor elite housing have been positively identified. Both documentary and archaeological evidence make clear that the Chachapoya were far more fractious and unruly than the Central Andean Wanka and other “classic” Andean chiefdoms.

After Inca conquest around 1470, imperial administrators installed a nested hierarchy of curacas and lower-level lords overseeing tributary units portioned in accordance with the Inca decimal accounting system. The Inca divided the new Chachapoya province into several hunos (groups of 10,000 tribute payers each), split into northern and southern divisions. Following the European conquest, a great deal of litigation occurred in Leymebamba in 1574, where local lords installed or displaced during decades of imperial machinations vied for legitimacy under the viceroyalty. The Inca had been forced to reconquer the rebellious Chachapoya at least twice, and repeated changes in political authority exacerbated factionalism, which further hinders ethnohistorical identification of pre-Inca political structures. A permanent state of political instability was the unintended result of consolidating local populations that subsequently forged a united resistance to Inca imperial authority. The resulting ethnogenesis of a unified Chachapoya group actually fortified an insurgent movement that leapt at the first opportunity to ally itself with Pizarro’s Spanish forces against the Inca.

Religion

Documentary and archaeological sources render a picture of Chachapoya ayllus venerating ancestors, which they interred in “open” sepulchers built into cliff faces. Los Pinchudos, Laguna de los Condores, and Revash provide examples of mausolea where prominent kin groups maintained access to mummies and consulted with the dead on earthly matters. From these promontories, the ancestors “oversaw” community lands dotted with sacred landmarks central to memories of the mythical past. Mountains, prominent rocks, trees, and other natural features in the landscape could embody ancestor spirits that bestowed water and fertility upon the land. Ayllus looked to lakes, springs, and caves as places where their original “founding” ancestors emerged. A less typical Chachapoya mortuary practice was the enclosure of individual seated cadavers in conical clay capsules arrayed in rows along cliff faces. The most famous of these purunmachus are found at the site of Karajia, where the clay sarcophagi exhibit modeled heads and faces and elaborate red-painted decorations. Mortuary ritual included the painting of pictographs, usually large red concentric circles, on the rock above tombs. In short, the Chachapoyas landscape was animated with local ancestors, prompting Inca efforts to superimpose imperial symbolism through landscape modifications and new constructions. In this way, they legitimized their presence in Chachapoyas territory and exerted a measure of ideological control.

Although the details of Chachapoya mortuary practices are unique, local religious beliefs were evidently not unlike those of other Andean cultures. The Chachapoya were purportedly unified in their belief in a common deity, which, if true, may reflect construction of regional Chachapoya cultural identity through the metaphor of common descent from a single apical ancestor. Chroniclers mention the local worship of serpents and the condor as principal deities. The serpent is the single most prevalent image in Chachapoya iconography, appearing in pottery and architectural embellishments. Details of other local deities and cyclical rituals performed to propitiate agriculture remain unknown. Apparently, the Chachapoya did not build temples dedicated to indoor ritual, although outdoor spectacles and feasts certainly took place in central plazas. Excavations in prominent buildings at the sites of La Playa and Gran Pajaten did yield quartz crystals, rare metals, and other evidence for ritual activities, perhaps within elite habitations, but no similar evidence has yet been reported elsewhere in Chachapoyas. Chronicles pro-vide an inordinate number of references to powerful sorcerers, or “shamans,” in this region. The importance of Chachapoya shamanism likely has local roots and probably relates to the accessibility of herbs, narcotic plants, and esoteric knowledge at a major gateway to the Amazon lowlands where the greatest shamans reputedly dwelled. However, social and political chaos during the colonial period probably led to widespread increase in the hostile sorcery witnessed by the Spaniards.

Art and Expressive Culture

Chachapoya art and iconography as we know it present themes of war, male sexuality, and perhaps shamanic transformation into alter egos, such as felines. Much expressive culture surely relates to ancestor veneration and agricultural propitiation, but such interpretations rely heavily on indirect evidence. The Chachapoya are most widely known for their stone carving and architectural skills, yet they have been described by chroniclers as among the greatest of Andean weavers. Still, Chachapoya textile arts remained virtually unknown until archaeologists rescued approximately 200 mummy bundles in 1997 from ongoing looting at the cemetery at Laguna de los Condores. The extraordinary preservation at the cliff cemetery now permits experts to unravel the details of Chachapoya weaving techniques and iconography. Designs on textiles, pyro-engraved gourds, and other media typically include representations of serpents, felines, and other fanged creatures, and feline-human hybrids. Anthropomorphic wooden sculptures accompany the dead at the Laguna and hang from ingenious wooden hinges beneath the eaves of mausolea at Los Pinchudos. Because of preservation conditions, wooden sculpture remains unknown elsewhere in the Andean highlands. An obsession with human heads, most frequently carved in stone and incorporated into building masonry, may represent concern for ancestors or trophy heads taken in war. These are among the most significant finds in a growing corpus of artistic media that promises to shed new light on Chachapoya culture. Unfortunately, the problem of looting at Chachapoya tombs is expanding, and sustained scientific archaeology in the cloud forest is a difficult and expensive enterprise.

References:

- Church, W. (1994). Early occupations at Gran Pajaten. In Andean Past, 4, 281-318. (Latin American Studies Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY)

- Schjellerup, I. (1997). Incas and Spaniards in the conquest of Chachapoyas (Series B, Gothenburg Archaeological Theses No. 7). Göteborg University, Sweden.

- von Hagen, A. (2002). Chachapoya iconography and society at Laguna de los Condores, Peru. In H. Silverman & W. Isbell (Eds.), Andean archaeology II: Art, landscape and society (pp. 137-155). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.