Rome and its vast literature and civilization formed the point of departure for scholarly investigation during the 19th century beginnings of anthropology, archaeology, and sociology. At the time, university admission required the knowledge of both Latin and Greek. This educational practice had begun during the Renaissance and was only dropped during the mid-1960s in Europe. For many, Greek and Roman civilizations were the first “alien” civilizations encountered.

The history of Rome and its empire covers over a thousand years. From obscure, mythical beginnings, Rome went on to rule the ancient world. Its political power and cultural influence reached beyond its well-defended borders and were supported by the way Roman society was organized and by its (initially) generous treatment of its allies. Between approximately 600 BCE and 200 BCE, a long-running struggle took place between the patricians and the plebs, and a republic of sorts emerged, which lasted in name until 44 BCE, when a battle for ultimate power arose among the patrician generals. Rome became an empire that relied on military strongmen to defend its interests and to pursue the expansion of its territory to support the center. In the fifth century CE, the western Roman Empire fragmented under the joint pressures of barbarian invasions and internal economic weakness.

Roman Social History

Rome was situated at an important river crossing approximately 17 miles inland from the mouth of the Tiber, and thus was in a position to control trade into the back country. The city had a mixed population of locals and foreigners from its very beginnings.

The common inhabitants of Rome were originally divided into three tribes (either related to the root “tres”—three—or thought to derive from “trifu,” a term used on some second century BCE bronze tablets found in Umbria, where it appears to mean “community”). Later, more tribes were created to accommodate the inhabitants of the incorporated territories, those where Roman citizens had settled or whose original population had been incorporated as citizens. There were always four tribes for the city of Rome, and, ultimately, 31 “rustic” ones. Every citizen had to belong to a tribe, and personal names would be ordered as follows: first or given name; then the family name or, in the case of patricians, the name of the gens (clan); next the name of the father; then the name of the voting tribe; and last, a cognomen, frequently an optional nickname. The standard example is always Marcus (preanomen) Tullius (his gens) Marci filius (son of Marcus) Cornelia tribu (voting tribe) Cicero (cognomen). Later, these cognomina became more popular than the first or given names, and during the empire even the plebs began to use them.

Roman citizens were also divided according to wealth into a classis (group or class; plural: classes); the two classes were those who could afford to arm themselves and the rest, who could not. During the fifth century, at the time of the Middle Republic, this rough division was refined into five classes: three that functioned as heavy infantry, and two as skirmishers. During the Late Republic, the division into classes was also used for tax purposes. Until 167 BCE all individuals had to pay tributum or direct taxes, an amount that could vary from year to year according to the needs of the state. After that date, all citizens, inhabitants of Italian coloniae or Italy itself, were exempt: the wealth that came from the provinces, which were under direct government of the Roman state, was sufficient.

Decisions about which class one belonged to were in the hands of two patrician censors (later plebeians were eligible as well), who conducted a census every four or five years. Those who were too poor to contribute in any way to the well-being of the state were called “proletarians” because the only thing they provided was their proles, or offspring. The classes similarly served to assign people to voting groups that made up the original assembly, the comitia centuriata. The majority within each group decided the vote for that group. The voting system in Rome was more complex than described here, but it appears to have been weighted in such a way that the aristocracy could outvote the plebs and the old the young. During the Late Republic and imperial times, the censors also judged people’s morals and could remove those they objected to from the voting rolls. Censuses were conducted not only in Italy but also in the provinces and colonies.

The plebs consisted of all those who were not of patrician descent. Originally, members of the plebs were not allowed to hold religious positions and were excluded from the senate and magistracies and forbidden to intermarry with patricians, but they did have to serve (if they could afford it) in the army. During the Conflict of the Orders, a period of approximately 200 years, the plebs organized itself, and set up a parallel government on various occasions. Secessio, where the entire plebs of Rome would leave the city, occurred several times: gained were inviolability for its officers, the tribunes, and a host of other benefits and laws as well as political equality with the aristocrats for the wealthier among them. Eventually, the rights and officers were absorbed into the larger structure of the government of the populus Romanus.

It is calculated that slaves made up approximately 10% of the population of Italy; most slaves were prisoners of war, or had been kidnapped by pirates raiding the Mediterranean seaports. Owning slaves was a symbol of wealth: some owners had several thousand, others just had two or three. A child of a free man and a slave woman would be free, and many Romans would promise freedom to their slaves after a certain number of years of work. Freedmen would receive (limited) citizenship, and some rose to high positions in imperial times. Slaves could be used for agricultural work, crafts, teaching, mining, or gladiator fights, and could be secretaries, administrators, and so on. In such capacities they worked alongside citizens. The state owned a large number of slaves for public works.

The population of Rome during the first century CE consisted of about 1,000,000 inhabitants, who were mostly supported by the subsidies provided by rich members of the elite, eager to buy votes. Panem et circenses, bread and games, were a real phenomenon. The many religious holidays provided plenty of opportunity for handouts. Of all games, the gladiatorial ones were the most famous. The games originated in Etruscan funeral practices, and remained popular in Italy and in its colonies until they were forbidden in 325 CE They involved vast expense, and emperors vied with each other in outspending their predecessors: a clear case of conspicuous consumption and influence buying. The contestants often were slaves, prisoners of war, condemned criminals, or citizens who had sold themselves for a fee. The gladiatorial games were held in the Forum during the republic, and later in the Colosseum, which could hold up to 55,000 spectators.

There were many other ludi (games) as well: chariot races, for instance, were held in the Circus Maximus, which could contain up to 150,000 spectators and provided permanent tiered seating. Many of the ludi were held on religious holidays, whose number increased from about fifty in republican times to close to 180 in the fourth century CE Gambling and betting on the different teams was common, as were fights among the fans and factions. Other ludi are the ludi scaenici, or theatrical performances, which began during the mid-fourth century BCE Initially, performances consisted of mimes and pantomimes, with some musical accompaniment. Later, plays (comedies, tragedies) could be performed anywhere, but they were often connected with temple festivals; temporary seating and stages would be set up. Only in the first century BCE were permanent theaters constructed. Ludi scaenici were often paid for by the state and the presiding magistrates. Women and children could attend, but were seated separately from the men. On days of festivals, the courts would be closed, certain agricultural chores were restricted, and some workers would get the day off.

The Roman Family and Roman Religion

The term familia could mean “the household”: it would include all those who lived in a house, including the slaves. Freed slaves would take the name of the person who had freed them and continued to belong to the familia. Roman family structure favored the male line: the paterfamilias and all his close bloodline were called agnati (sing. agnatus). A woman who married into a family became agnata as well. She could avoid this fate by spending three nights of the year elsewhere, in which case she continued to be a member of her own father’s line, and her property would remain her own. Cognati (cognatus) were all those linked by blood; adfines were those one was related to by marriage. The paterfamilias held power over his entire household and could order the death of his children, forbid marriage, or order divorce. Unless a father released his son from patria potestas, the son would remain dependent on his goodwill.

Roman patricians worshipped their male ancestors and had masks representing them hanging in their houses. These masks were worn by actors during important religious events in the family, or during funeral processions en route to the pyre. The lower classes also practiced cremation, the custom in most of Western Europe from approximately the third century BCE until the middle of the second century CE, when the Hellenistic custom of burial took over. The poor often belonged to “funeral clubs” that helped defray the expense. The spirits of the dead were believed to go to the underworld; those refused entrance would wander the earth. Relatives would visit graves and bring offerings of food or small gifts.

Roman patricians worshipped their male ancestors and had masks representing them hanging in their houses. These masks were worn by actors during important religious events in the family, or during funeral processions en route to the pyre. The lower classes also practiced cremation, the custom in most of Western Europe from approximately the third century BCE until the middle of the second century CE, when the Hellenistic custom of burial took over. The poor often belonged to “funeral clubs” that helped defray the expense. The spirits of the dead were believed to go to the underworld; those refused entrance would wander the earth. Relatives would visit graves and bring offerings of food or small gifts.

The Roman household had its own protective spirits, the Lares and Penates, who were worshipped in the home. The state had its own set. In general, it can be said that the Roman religious pantheon very closely mirrored the Roman family: an all-powerful father (Jupiter) and a close set of cognati. Later, when Greek culture became more influential, the Greek pantheon was “translated” into the Latin one, and characteristics of the gods were adjusted. Once the Middle East was conquered, the emperors found it to their advantage to claim divine descent and demanded to be worshipped the way Eastern potentates were worshipped.

This created problems at home, not so much among the plebs as among the other patrician families, and among the adherents of new cults, such as Christianity.

Originally, education of young aristocrats took place at home; both mothers and fathers were involved. But during the late second century BCE Romans began to feel the need for a more thorough education: the conquest of Greece no doubt had much to do with this. Greek teachers and slaves (to teach) were in high demand, and during the first century BCE all children of patricians (some girls, as well) grew up bilingual. From an early age patrician boys were trained in oratory—after the Greeks arrived, in rhetoric, a more systematic approach to giving speeches and arguing with political opponents. Young men would “finish” their education by studying a few years in Athens or in Alexandria, which was also Greek-speaking. Or, if they wanted, they could study law in Berytus (Beirut), which had a flourishing law school after the first century CE. They could also stay in Rome and attend law school there. With Greek culture came the Greek approach to life and its pleasures, and many conservatives railed against the graeculi (the Greeklings). The first century BCE witnessed the growth of Latin literature: much of what is read and studied today was produced during that period or shortly thereafter.

Roman Administration

Rome’s expansion was successful due to its administrative organization. Once it had conquered an enemy, this enemy could become an ally on very generous terms, or else, the city would be razed to the ground. The creation of colonies began in the fourth century BCE, first on Italian soil, later anywhere else. The colonists had their own magistrates and organization, retained their Roman citizenship, and were expected to perform military duties if required. Local patricians also received privileges and developed loyalty to Rome. During the time of the emperors (beginning ca. 50 BCE) the system was expanded beyond the borders of Italy, and colonies were established as far away as Germany, Spain, Britain, north Africa, and the Middle East.

Of old, the senate played an important part in governing Rome; the senators’ power, however, was frequently limited. The origins of the senate are obscure, and it is not certain that it was made up entirely of patricians from the beginning. To be a member one had to own a certain acreage. The number of senators varied over the centuries from 300 to almost a thousand in the mid-first century BCE. The son of a senator would also be a senator, of course, but the highest magistratures went to those who had earned the right to them. High status was conferred, not inherited, and a military career was the surest way to glory and success. Another way was to become an expert in Roman law—especially during the last four centuries of the empire. During republican times, former magistrates became members of the senate for life, and thus controlled most aspects of government, making financial as well as military and religious decisions. Originally the representatives of the plebs could only attend the senate by sitting in the vestibule of the senatorial meeting hall; later, they acquired the same privileges as the patrician senators. By the end of the republican period, however, the senate had lost all power.

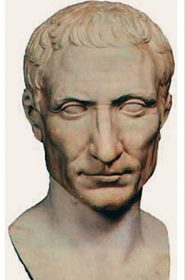

The republic effectively ended with the rise of Gaius Iulius Caesar (100-44 BCE). Although he never took the title of emperor (Imperator), he certainly created the model. By means of intrigue, bribery, dubious loans, marriage and other alliances, and brilliant military, political, and oratorical skills, Caesar, a patrician by birth, managed to gain the trust of the plebs and the loyalty of his soldiers. To ensure his succession, Caesar had adopted his great-nephew Octavian, since he had no sons himself. Octavian, although only 18 at the time of Caesar’s death, was as gifted in military and political skills as his great-uncle or “father.” He took the religious title of Augustus (“consecrated” or “holy”) in 27 BCE, thus becoming the de facto first emperor, although he claimed to have restored the republic.

The republic effectively ended with the rise of Gaius Iulius Caesar (100-44 BCE). Although he never took the title of emperor (Imperator), he certainly created the model. By means of intrigue, bribery, dubious loans, marriage and other alliances, and brilliant military, political, and oratorical skills, Caesar, a patrician by birth, managed to gain the trust of the plebs and the loyalty of his soldiers. To ensure his succession, Caesar had adopted his great-nephew Octavian, since he had no sons himself. Octavian, although only 18 at the time of Caesar’s death, was as gifted in military and political skills as his great-uncle or “father.” He took the religious title of Augustus (“consecrated” or “holy”) in 27 BCE, thus becoming the de facto first emperor, although he claimed to have restored the republic.

The rise of Christianity during the first and second centuries CE created increasingly larger problems for the Roman empire. Originally seen as a sub-sect of the Jewish religion, Christians had been given the same exemptions as the Jews: as monotheists, their religion was not absorbed into the larger Roman religious system, and some autonomy had been given to some Jewish territories. Only in the third century CE was Christian dogma sufficiently established to be seen as a threat to the Roman state; however, by that time the Church had so many members that intolerance was no longer an option.

It is calculated that by the second century CE, the territory ruled by the Empire covered about 2 million square miles, with a population of approximately 55 million. In 293 CE, to facilitate rule and to better control corruption, Diocletian (a usurper himself) split the Roman empire into two: a Roman (western) half, and a Greek half (with its capital in Byzantium).

The third and fourth centuries CE saw increasing attacks from northern tribes, the Goths, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, the Vandals, various Germanic tribes, and in 476 the western Roman Empire was no more. Roman culture (including language and dress) was henceforth transmitted by the Catholic Church and the Pope.

References:

- Adkins, L., & Adkins, R. A. (1994). Handbook to life in ancient Rome. New York & Oxford: Oxford

- University Press. Whittaker, C. R. (2004). Rome and its frontiers: The dynamics ofempire. London and New York: Routledge.