Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted from approximately 3000 BC until the date of the last known hieroglyphic inscription in 395 AD. Though many cultures invaded and at times ruled Egypt, its character survived largely the same until the Roman Period, and many aspects of ancient Egyptian civilization remained through the Coptic Period. Egypt did not attain international prominence until the time of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2686-2125 BC) and increased in power until its height of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550-1069 BC), when its empire stretched from present-day Sudan to the Euphrates River and eastern Turkey. The fortunes of Egypt have always been intertwined with the Nile River and its canals, along with expeditions to gain precious resources in remote neighboring regions.

Egyptology as a discipline did not fully develop until Jean-François Champollion’s decipherment of ancient Egyptian in 1822, and since then, it has dealt with all aspects of ancient Egypt, including language and literature, architecture, archaeology, art, and overall historical developments. Major finds, such as the tomb of Tutankhamun, the workmen’s village at Giza, and, more recently, the origins of the alphabet have fueled public interest in Egyptology and the field as a whole. With archaeologists and historians making great discoveries every year, the perceptions of key issues in ancient Egyptian civilization continue to change.

History of Egyptology

Ancient Egypt has never been completely lost to the world, and the concept of its rediscovery is largely through Western eyes. It remained a popular place to visit during Roman times, with many items on the ancient itinerary remaining the same today, including the pyramid fields and the ancient capital city of Memphis. Numerous pilgrims visited St. Catherine’s monastery, in South Sinai, during medieval and crusader times. Many early Muslim scholars held ancient Egypt in high regard and wrote treatises on its language and architecture. Though largely incorrect, these papers give insights into the importance of ancient Egypt long after its hieroglyphic system of language went out of use.

European crusaders returned with many stories of their travels, inspiring others to take the same journey to see the wonders of the ancient Near East. The idea of the pyramids as the “granaries of Joseph” has its origins in the writings of Julias Honorus and Rufinus, as well as a 12th-century depiction in one of the domes of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice. This and other tales renewed interest in the history of the pagans during the Renaissance. With the creation of the printing press and increased protection for travelers after Egypt fell under Turkish Ottoman rule in 1517, travelers soon became antiquarians, collecting artifacts and manuscripts for libraries and museums.

Egyptology has its roots in the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt in 1798, when Napoleon’s army, accompanied by engineers, draftsmen, artists, botanists, and archaeologists, mapped the whole of Egypt. Along with documenting modern and ancient Egypt, they collected artifacts and specimens over a 3-year period and produced a series of volumes entitled the Description de LLEgypte. With Champollion’s decipherment of hieroglyphs and increasing interest in the culture of ancient Egypt, numerous collectors flocked to Egypt, including Henry Salt, Giovanni Belzoni, and Bernardo Drovetti, all of whom contributed to the growing collections of the British Museum, in London; the Musée de Louvre, in Paris; and Museo Egitzio, in Turin.

Archaeological expeditions increased in frequency as well, with investigations led by Auguste Mariette, Gaston Maspero, and Eduard Naville. William Mathews Flinders Petrie, considered by many to be the father of Egyptian archaeology, pioneered detailed recording methods in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. American and European scholars conducted numerous other studies, and Egyptology experienced increased interest after the discovery in 1922 of a virtually intact tomb of a relatively minor 18th dynasty pharaoh, Tutankhamun, in the Valley of the Kings, in Luxor, by Howard Carter and his patron, the Earl of Canarvon. Today, over 400 foreign expeditions work in Egypt alongside many local excavations, under the auspices of the Supreme Council for Egyptian Antiquities.

Geography

Egypt is characterized by the Nile river floodplain between harsh desert lands composing its eastern and western frontiers. Long considered the breadbasket of the ancient world, Egypt relied upon Nile floods to sustain its agricultural economy. Even during ancient times, Egyptians called their country kemet, meaning “black land,” referring to the rich silts deposited annually by the Nile inundation. The harsh desert world, dominated by chaos and inhabited by liminal creatures, was known as deshret, or “red land.” The interplay of the dual concepts of black land and red land, order and chaos, symbolize parts of ancient Egyptian religion and mythology.

The Nile River is 6,670 km long and covers 34 degrees of latitude, from 2 degrees south of the equator to 32 degrees north in Egypt’s delta, and then drains into the Mediterranean. The waters of the Nile come from Lake Tana in the Ethiopian plateau (at 1,830 m elevation) and Lake Victoria in East Africa’s lake district (at 1,134 m elevation). These lakes connect to the Blue and White Nile basins in sub-Saharan Africa and before the phases of Aswan high dam construction (in the early 1900s and 1960s) relied on annual monsoon rainfalls to fill these basins for good flood levels. Higher flood levels meant a good harvest, good fishing, and better grass for grazing. Floods were so important to the ancient Egyptians that they connected the annual flood to the religious myth of the wandering eye of the sun, which told the story of the goddess Hathor bringing annual inundation waters from the south. The rise and fall of different aspects of ancient Egypt are also closely connected to flood levels. Predynastic material culture first starts to appear after a period of high then low floods around 4,200 BC to 4,000 BC. The end of the Old Kingdom was potentially connected with a series of disastrous flood years followed by drought. Ancient Egyptians measured flood levels by a series of Nilometers, several of which survive to this day.

The eastern and western deserts represent outside areas with many mines and trade routes. The eastern desert has many mines, including alabaster and quartzite quarries, and numerous rock inscriptions. The western desert contains the oases of Dakhla, Farafra, Kharga, and Bahiriyah, which contain important trading settlements and outposts guarding the western desert from invading forces. Sinai represents an important region for copper and turquoise mining at Serabit el-Khadim and Wadi Magahra, while north Sinai existed as part of the “Way of Horus,” an ancient fortification route connecting Egypt to Syria-Palestine.

History and Chronology

An Egyptian priest named Manetho in the 3rd century BC divided ancient Egypt into 30 dynasties, which current Egyptologists generally retain in their historical analyses. Though this method of dating continues, it is slightly passé with current discoveries in ancient Egyptian chronology and the utilization of radiocarbon dating. More emphasis has been placed on socioeconomic trends and less on political events. Periods are no longer understood only in historical events, but in terms of material culture shifts. Three approaches mark the way in which Egyptologists deal with ancient Egyptian chronology, which include relative dating methods (such as seriation with pottery or coffins, or stratigraphic phases), absolute chronologies (including astronomical and calendrical events in ancient texts), and radiometric methods (radiocarbon dating and thermoluminescence).

A unified Egyptian state did not appear until 3200 BC, but it had its origins in the preceding Naqada culture, which lasted from about 4000 BC to 3200 BC and lay to the north of present-day Luxor. Petrie found 3,000 graves dating to the Naqada I Period. They represented simple burials in pits with wooden or ceramic coffins. The Naqada II Period saw an increase in funerary offerings, as well as painted pottery, showing the early development of ancient Egyptian art and artisans. During the Naqada III Period, Egypt unified into a large state with major political consolidation, and there were increases in cereal production with improvements in the irrigation system. The unification between Upper and Lower Egypt took place through a combination of warfare and alliances, yet throughout ancient Egyptian history, an emphasis was placed on the divided nature of the country, with one of pharaoh’s titles being “King of Upper and Lower Egypt.” Important artifacts showing warfare and kingship around the time of unification include the Narmer Palette and Macehead, and early international relations can be seen at tomb U-j at Umm el-Qa’ab, Abydos, with 40 imported jars, possibly from Palestine.

Egypt’s early dynastic state emerged about 3200 BC, with Memphis as an important political center and Abydos as a central cult center. Though evidence for some early cities survives, most of Egypt would have existed as small settlements during this time. Basin irrigation gave way to large state-controlled irrigation, allowing for increased crop growth. Writing was introduced during this time, used in art, administration, and for the economy, and the iconography of power and kingship developed as well. Cult centers linked towns and regions, while the tombs of the Dynasty 1 kings developed in form and function at Abydos. Archaeologists discovered early body preservation techniques at Saqqara, with an increase of the use of wooden coffins seen at the end of Dynasty 2. Taxation and increase of state power led to more expeditions being sent to Nubia, Sinai, Palestine, and the Eastern Desert for acquisition of goods. This led to a formalization of the bureaucratic structure that formed the basis of Egyptian society for much of its history.

Egypt’s Old Kingdom (Dynasties 3-6) did not differ much politically from the early dynastic period, with the royal residence still located at Memphis, yet architectural innovations reveal the overall growth and consolidation of state power. The construction of Djoser’s step pyramid complex at Saqqara and the development of the true pyramids at Giza, Medium, and Abusir demonstrate the internal organization and power of kingship needed to effectively join its people and resources. Artisans, scribes, architects, and skilled laborers became essential parts of ancient Egypt’s societal fabric, and religion developed, with royal mortuary cults and increasing importance of the god Ra. Nomes began at the start of the Old Kingdom and divided the country into regional administrative units, with 22 nomes in Upper Egypt and 20 nomes in Lower Egypt led by nomarchs, or regional governors. A breakdown in royal administration with the 94-year rule of Pepy II (ca. 2278- 2184 BC) and growth in the power held by the nomarchs led to the “collapse” of the Old Kingdom, as well as important environmental factors, including a period of drought.

The following First Intermediate Period (ca. 2160-2055 BC), Dynasties 7/8 to mid-11, represents a time of political upheaval and unrest in ancient Egypt. The royal residence shifted from Memphis in the north to Herakleopolis in central Egypt, with an opposing band of rulers emerging at Thebes in the south. Although the overall political structure may have changed, development took place on a local level, with tombs, pottery, funerary models, and mummy masks. War raged between the Theban and Herakleopolitans (who connected themselves to the Memphite court traditions) for control of Egypt, with local rulers taking the place of pharaohs for care of their people. The Theban “royalty” took over the Herakleopolitans stronghold at Asyut, followed by their capital at Herakleopolis, and thus the beginning of the Middle Kingdom and late Dynasty 11.

While late Dynasty 11 ruled from Thebes, the court of the 12th Dynasty and the first half of Dynasty 13 moved to the Fayoum in the period known as the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055-1656 BC). Known as the “renaissance” period in ancient Egyptian history, the Middle Kingdom had many developments in art, architecture, and religion. Nebhepetre Montuhotep II (ca. 2055-2004 BC) reunited Egypt and increased construction projects, including his mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri and developments in art, and dispatched commercial expeditions once again into Sinai and Nubia. His son, Mentuhotep III, sent the first Middle Kingdom expedition to Punt (eastern Sudan and Eritria) for incense. In Dynasty 12, the capital moved to Ijtawy, near the Fayoum, under the reign of Amenemhet I, to administer a reunited southern and northern Egypt. The government became more centralized, with a growth in bureaucracy and in town organization. Osiris became an increasingly important god, and mummification became more widespread.

In the succeeding Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1650-1550 BC), Egypt divided into two kingdoms, with the capital in the Fayoum moving to Thebes (southern Egypt), while an Asiatic kingdom (The Hyksos) arose in the Delta through graduated migration, settlement, and some invasions in the east. Evidence exists for a widespread Asiatic (Hyksos) material culture in Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Cyprus, as early as the Middle Kingdom. They ruled from Avaris in the eastern Delta during Dynasties 14 and 15, while a rival Egyptian kingdom (Dynasties 16 and 17) ruled from Thebes. The Hyksos controlled northern Egypt from the Delta to Hermopolis, with Cusae in Middle Egypt marking the southern frontier. Military might grew again in Thebes, with the ruler Kamose controlling the gold routes to Nubia and incorporating mercenaries into his army. Kamose began a 30-year war against the Hyksos, continued by his son Ahmose, who attacked Tell el-Hebua (the eastern military headquarters) and then Avaris, to drive out the Hyksos for good.

Ahmose initiated the New Kingdom (ca. 1550— 1069 BC), a period of great renewal and international involvement. The New Kingdom saw additional military action and colonization in Nubia, and campaigns to the Euphrates River in Syria under Thutmose I. These campaigns intensified under Thutmose III, who consolidated Egypt’s empire in the Levant. Improvement in mummification occurred, and the Valley of the Kings became the location for royal burials. The village of Deir el-Medina housed the workmen for the Valley of the Kings. Karnak temple and the cult of Amun-Re grew in size and prominence during the reign of Hatshepsut, daughter of Thutmose I; she built her famous mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Additional military successes in Nubia and Syria-Palestine brought additional wealth pouring into Egypt’s coffers, allowing Amenhotep III to build on unprecedented levels during his reign. His son Amenhotep IV, or Akhenaten, broke away from a polytheistic religious tradition to found a new capital city at Tell el-Amarna, in Middle Egypt, and implemented a worship of primarily one god: the Aten (the sun’s disk). This move and religious shift affected cultural and religious traditions for a long period of time. Tutankhamun moved the capital back to Memphis, reinstated the cults of other gods, and returned Thebes and the cult of Amun to their positions of prominence. Late Dynasty 19 and 20 represented the Ramesside Period, during which Seti I built new temples and conducted several large military campaigns against a new enemy, the Hittite empire. Ramses II led campaigns as well, and built a new capital at Pi-Ramses in the eastern Delta. Egypt’s Levantine empire and other east Mediterranean cultures fell to a mass migration of Sea Peoples, sea raiders, and displaced refugees, with Ramses III saving Egypt from invasion. Egypt declined slowly under Ramses IV through XI, losing its empire, power, prestige, and cultural unity.

Foreign incursions and economic weakening led to civil war, and the start of the Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1069-664 BC). When the viceroy of Kush (governor of Nubia) invaded Egypt, Dynasty 21 began in the north at Tanis under Smendes (ca. 1069-1043 BC), while the high priest at Thebes effectively ruled in southern Egypt, albeit acknowledging the sovereignty of Dynasty 21. Sheshonq (ca. 945-924 BC), a Libyan, started Dynasty 22 and reaffirmed the political power of the king. Dynasties 22 through 24 are called the Libyan Period, which ruled primarily from the western Delta. Dynasty 25 started when the Kushites invaded from Nubia and took over Egypt through military might. The Kushites reverted to more traditional religious practices and copied Old Kingdom art in a form of archaism, to reaffirm their rule.

The period of the Assyrian empire and sporadic invasions of Egypt spanned Dynasties 25 through 26 and the beginning of the Late Period (ca. 664-332 BC). Dynasty 26 covers the Saite reunification of Egypt under the rule of Psamtik, who made Sais his capital in the western Delta. After a brief period of Saite imperialism, the first Persian occupation of Egypt, Dynasty 27, took place when Cambyses defeated Psamtik III in the Battle of Pelusium in around 525 BC. In Dynasties 28 through 30, Egypt gained independence from around 404 BC through 434 BC. Increasing Persian threats added to the growing instability of ancient Egypt. In the second Persian occupation period, from around 343 BC through 332 BC, Artaxerses III assaulted Egypt and fought against and defeated Nectanebo I and II, the last pharaohs of dynastic Egypt.

Alexander the Great invaded Egypt in around 332 BC and founded Alexandria, a major center of wealth, knowledge, and intellectual activities. After his death, control of Egypt went to his general Ptolemy, which began the Ptolemaic Period (ca. 332-30 BC). This period was marked by a series of short-lived rulers, of whom Ptolemy I was the only ruler to die of natural causes. The great Rosetta stone, later responsible for allowing the deciphering of ancient Egyptian, was a decree written during the reign of Ptolemy V in 196 BC, describing homage paid to the ruler after he endowed Ptolemaic temples.

The native Egyptian culture and accomplishments declined after the reign of the famous queen Cleopatra VII, a brilliant and shrewd leader who spoke many languages (including Egyptian). Her affairs with both Julius Caesar and Marc Antony led to Egypt’s defeat by Rome at the Battle of Actium in September of 31 BC. Though the Romans controlled Egypt, its culture con-tinued, with additional temples constructed and its religion becoming a Romano-Egyptian hybrid. This culture lasted until Christianity was adopted in the 3rd century AD, and by the time of the Islamic invasion in AD 662, it had ceased to exist.

Language

Egypt’s language went through many stages in its development, and continuing advancements in textual and grammatical studies are helping to elucidate key historical issues. Muslim scholars in medieval times correctly identified 10 letters in its alphabet, while attempts to translate the language in the 1600s and 1700s produced a broad range of theories, many of which had humorous results. Despite serious studies by a Jesuit scholar, Athanasius Kirchener, the first serious efforts to translate the language took place with Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion. Champollion, a linguistic genius who had long been a scholar of Coptic, studied what became known as the “Rosetta stone,” discovered by Napoleon’s army in the western Delta. This stone has three inscriptions, in Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Champollion used his knowledge of Greek to translate the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra in hieroglyphs, and proceeded to hieroglyphs based on his newly found knowledge of the alphabet. His results allowed scholars access to a language that had been dead for over 1,400 years.

Proto-Egyptian hieroglyphs have been found on seals from tomb U-J at Abydos, with the language developing Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian forms. There are 24 letters in the ancient Egyptian alphabet, with the language using alphabetic, phonetic, and ideographic signs as well as determinatives at the end of words. In total, there are over 4,000 hieroglyphic signs. The cursive form of ancient Egyptian, known as Hieratic, became the script used in business matters, while Demotic developed in the 5th century BC. Coptic was the last stage in the development of ancient Egyptian, though the form spoken by the ancient Egyptians, the Sahidic dialect, has now been replaced by the Bohairic dialect. The language survives today in numerous forms: on temple and tomb walls, on ostraca (usually limestone and pottery fragments), and on papyrus, in religious, economic, and political documents.

Religion

Ancient Egyptian religion took many forms, including formal state religion maintained by priests in temples and in annual festivals, and more regional and personalized religious traditions in village shrines and homes. Ancient Egypt had several creations myths; in one, Egypt began by rising out of a watery nothingness as a primeval mound, upon which life sprouted forth. Another myth involves the god Ptah creating the world, while another myth related that the god Amun-Ra had created the world beginnings. Priests played important roles in temples to the gods and deified kings, while the pharaoh represented a living embodiment of the god Horus on earth, acting as an intermediary between the gods and humanity.

A number of ancient Egyptian religious documents survive, providing a religious code and enabling the deceased’s soul to safely and successfully journey to the afterlife. These books are known as the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, and Book of the Dead (the mortuary texts from the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms), while the New Kingdom religious compositions include the Book of the Heavenly Cow, Book of the Gates, and other underworld books. Select scenes and passages from these documents occur on tomb walls, sarcophagi, and mummy cases. Personal piety increased during the New Kingdom after the Amarna Period, and amulets representing different aspects of deities were worn on occasions. Household shrines played an important role in the daily lives of ancient Egyptians, and local shrines offered a chance for commoners to participate in religion on a regional scale. Certain aspects of ancient Egyptian religion lasted through the Coptic Period, but most ancient practices died out with the introduction of Islam in AD 662.

Temples and Funerary Monuments

Numerous temples appear throughout Egypt, but none are as well known as the temple of Karnak, on the east bank of the Nile in Luxor. It was the temple of Amun-Re, creator of all things, known as “the place of majestic rising for the first time.” Karnak was simultaneously the divine residence of the god and an ever-growing cult; it played important roles in social, economic, and political events. Its construction began in the Middle Kingdom, and it grew continuously until Ptolemaic-Roman Periods. Over 80,000 people worked at Karnak Temple during the time of Ramses II (Dynasty 19). The temple itself has an east-west axis, with a main pillared hall, numerous pylons (twin towers flanking entryways), courts, and jubilee halls. The complex was dedicated to the Amun-Mut-Khonsu triad, with adjacent temples complexes constructed for Mut and Khonsu.

Five kilometers south of Karnak is another major temple, Luxor Temple, which was dedicated to Amun of Luxor, a major fertility figure. Built originally by Amenhotep III, Ramses II added a pylon, an outer court, and two obelisks. The Beautiful Feast of Opet was celebrated at Luxor Temple annually to celebrate the birth of the king’s ka (spirit) and to regenerate his divine kingship. Luxor Temple was later used as a Roman military camp, and the mosque of Abu el-Hagg was constructed on its grounds. Today, numerous sphinxes from the reign of Nectanebo line its entrance. There are still major finds within its grounds; an excavation in 1989 discovered many votive statues of divinities and kings buried in its courtyard to make room for new votive statues.

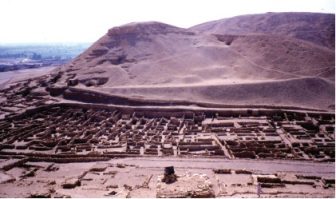

The Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens lie in western Thebes. The latter place represents the place for Pharaoh’s wives and children. The Valley of the Kings, known as “The Great Place,” or Wadi el-Biblaan el-Malik, “The Valley of the Gates of the Kings,” contained the burials for the kings of the Dynasties 18 through 20. In the Valley of the Kings are 62 known tombs, alongside 20 pits or unfinished shaft tombs. Despite the high-quality limestone of the hills and the protected and remote valley, the royal tombs still suffered robbery, mostly during the New Kingdom. The large quern or hill overlooking the region functioned as a focal symbolic pyramid. Today, over 1 million people visit the Valley of the Kings annually, making it one of the most popular archaeological sites in the world.

Numerous royal mortuary temples from the New Kingdom lie on the west bank in Luxor, built separately from the tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Over 20 were constructed in a 500-year period. Called “the mansion of millions of years” for each king, few remain standing today.

Settlement Archaeology

Egypt’s major settlements and provincial and national capital cities existed as political, cultural, and religious centers during key periods of Dynasties 1 through 30. In particular, the cities of Abydos, Memphis, Thebes (Luxor), and Alexandria formed particularly significant settlements for most of the pharaonic era.

Abydos, located 145 km north of Luxor, represented the burial place for the kings of Dynasties 1 and 2, with 10 known associated funerary enclosures. The subsequent Old Kingdom pyramid complexes originated from the royal cemetery at Umm el-Qa’ab, while the north cemetery at Abydos functioned as the burial place for commoners during the Middle Kingdom. The ancient settlement of Abydos is located at Kom es-Sultan, which spanned the Old Kingdom to the First Intermediate Period. Royal cult foundations existed at Abydos in both the Middle and New Kingdoms. For instance, the Osiris Temple of Seti I was constructed during Dynasty 19, with seven sanctuaries called “The House of Millions of Years.”

Memphis, which lies 25 km south of central Cairo on the east bank of the Nile, usually represented the capital of Egypt. Founded in about 3100 BC, its placement at the apex of the Delta, between southern and northern Egypt, and its access to desert trade routes made it an ideal administrative center. Memphis was the capital of Egypt in the Old Kingdom, lying near the Dynasty 12 capital at el-Lisht. In Dynasty 18, it was a powerful bureaucratic center, and in the Late Period and Ptolemaic Period, kings were crowned at Memphis. It existed as a religious center of pilgrimage for many years.

Luxor, or ancient Thebes, has archaeological material beginning in the Middle Kingdom. In the New Kingdom, it became a religious center for all of Egypt, containing major temples, tombs, and funerary monuments. It was known in ancient times as “the city” (much like New York today), with many festivals taking place throughout the year. Today, the modern city covers much of the ancient one, but excavation is starting to reveal the broad extent of Thebes at the height of pharaonic power.

Alexandria was founded in 332 BC at the northwest edge of the Delta opposite the Island of Pharos. It was five km long and 1.5 km wide, with the city divided into three equal parts. The famous lighthouse lay at the end of a bridge across the bay. Over 1 million people lived in Alexandria during its height, and it continued to be a major city throughout the Ptolemaic and into the Roman Periods. The library, housing tens of thousands of important scrolls and documents, appears to have burnt down during the conquest of Alexandria by Julius Caesar. In the late 4th century AD, Alexandria suffered extensive modification and destruction when temples became churches and many earthquakes damaged the city. The modern town covers much of ancient Alexandria, and new building construction continues to bring to light many important aspects of the city.

Future Directions

Modern urban developments, coupled with an increasing population, threaten many of Egypt’s archaeological sites. The rising water table is causing damage to innumerable monuments throughout the Nile Valley, and much is lost each year to the agricultural needs of the populace. Fortunately, the Egyptian government is working in partnership with many foreign expeditions in heritage management and conservation efforts. A new part of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, the Egyptian Antiquities Information Service, is attempting to document every known archaeological site in Egypt and aims to preserve as much as possible.

Technology is also playing an important role in the location, preservation, and reconstruction of archaeological sites, including remote sensing (both on the ground and in the air), 3-D modeling and mapping of sites, and digital scanning of monument inscriptions and reliefs. With many wonderful discoveries gracing the pages of newspapers and journals each year, Egypt’s past continues to offer much to its present.

References:

- Allen, J. (1999). Middle Egyptian: An introduction to the language and culture of hieroglyphics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bard, K. (Ed.). (1999). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge.

- Kemp, B. (1994). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a civilization. London: Routledge.

- Redford, D. (2002). The ancient gods speak: A guide to Egyptian religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shaw, I. (Ed.). (2000). The Oxford history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shaw, I., & Nicholson, P. (2000). Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilkinson, R. (2000). The complete temples of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson.