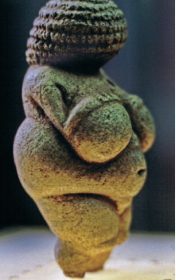

The Venus of Willendorf, a small female figurine with exaggerated sexual characteristics, is arguably the most famous example of Paleolithic portable art. It was found in 1908 by archaeologist Joseph Szombathy near the town of Willendorf, Austria, in loess deposits dated to the Aurignacian period (24000-22000 years BP). It is currently housed in the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Prehistoric art is generally categorized as either parietal cave/wall art, or portable art. Portable art consists of small, transportable objects made from stone, bone, antler, ivory, or shell. These objects could be obviously functional, such as spearthrowers, or without an obvious function, suggesting ceremonial or ritual use. Portable objects were decorated with images of animals, humans, or symbols; some were sculpted into animal and human figurines. The human figurines, found throughout Eurasia from Western Europe to Siberia, are almost exclusively female. These female statuettes are generally called “Venus figurines” because they depict a faceless, voluptuous, often corpulent, female body with a heavy emphasis on the breasts, stomach, buttocks, and pubic region.

The Venus of Willendorf is 11 cm (4.3 in) tall, carved from limestone, and fits easily into the palm of the hand. The figurine depicts a fleshy woman with heavy hips and voluminous belly and breasts. Her large hips and thighs taper to small ankles. Her arms are small and are resting above her breasts, and both her wrists are adorned with bracelets. Her head is tilted forward; no face has been carved. However,

much attention was given to her elaborate plaited hairstyle that extends down to the nape of her neck. The plaits are wrapped in seven concentric bands around her head. Originally the figurine was painted with red ochre. The statuette is made of nonlocal limestone, meaning that either the raw material or the finished product was brought to (or traded into) the site.

What do the Venus of Willendorf, and other Venus figurines, represent? With all art, the social context in which these figurines were carved holds the key to what made them meaningful to their owners. The social context, however, is not well understood for these nomadic Paleolithic societies, and there are many interpretations of the role of the Venus figurine.

The most commonly cited interpretation of these figurines is that of fertility fetish or fertility goddess.

To support this view, researchers point to the artist’s emphasis on the stomach, breasts, buttocks, and pubic area, suggesting sex and procreation. Some argue that the red ochre pigment originally covering the statue symbolizes menstrual blood, thought to be a life-giving material.

To support this view, researchers point to the artist’s emphasis on the stomach, breasts, buttocks, and pubic area, suggesting sex and procreation. Some argue that the red ochre pigment originally covering the statue symbolizes menstrual blood, thought to be a life-giving material.

A second interpretation of the Venus figurines is as a talisman. Its small size makes it possible for men to carry it during hunting trips. Its fertility symbolism, again, could be thought to help increase the number of animals, bringing hunting success. Some cite the facelessness of the figurine, suggesting it functioned more as a symbol rather than a representation of a person. However, others argue that to humans, the face is a key feature in identity; since the Venus figurines lack a face, they lack identity, and can be regarded as anonymous sexual objects.

For many researchers, the figurines’ fertility symbolism itself is questioned. Whereas some of the figurines appear pregnant, many are simply obese. For these active, nomadic Paleolithic hunting and gathering groups, obesity would be a rarity. None of the few male figurines or images from this period is depicted as obese. If this is an obese woman, she would perhaps have had a special status in the group. From this and the fact that these figurines are widespread geographically, some argue that the Venus figurines serve as an illustration of a prominent female deity identified as a mother goddess. Some researchers suggest that this reflects the relative importance, perhaps even dominance, of women in Paleolithic societies. Alternatively, its function might be tied exclusively to the female sphere, carved by women for women.

Despite the preponderance of explanations, the meaning of the Venus figurines remains elusive, and interpretations often reflect current society as much as that of its makers.

References:

- Bahn, P., & Vertut, J. (2001). Journey through the Ice Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Conkey, M. W., Soffer, O., Stratmann, D., & Jablonski, N. G (Eds.). (1997). Beyond art: Pleistocene image and symbol. Wattis Symposium Series in Anthropology, Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences Number, 23. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences.

- Marshack, A. (1991). The roots of civilization: The cognitive beginnings of man’s first art, symbol and notation (2nd ed.). Mt. Kisco, NY: Moyer Bell.