Located on the north coast of South America, Venezuela is a country of stunning scenery and extreme cultural diversity, including the forest-dwelling Yanomamo and modern Caracas with its economy fueled by petroleum. The climate is generally tropical, but diverse habitats from Amazon rain forest to tall, cold mountains support high biological diversity, including at least 21,000 species of higher plants and 323 mammals. With more than 40 living languages, Venezuela provides the stage for some of the most contentious debates in anthropology. Collaborative international research efforts have included Venezuelan, French, German, American, and other anthropologists.

Venezuela includes an area of 912,050 square kilometers—roughly the size of Texas and Oklahoma or France and Italy combined. The total population is 25 million, with an annual growth rate of 1.4%. Most people (85%) live in cities in the north, with more than four million in Caracas, the capital city. The literacy rate is high (91%). Venezuelans are relatively healthy, having a 73-year life expectancy at birth. Infant mortality is 26 per 1,000 live births. With a US $3490 gross national income per capita in 2003, Venezuela is one of the wealthier Latin American countries, although 58% of income is concentrated among the wealthiest 20% of the population.

Sustained European contact began in 1499 when the Spaniard Alonso de Ojeda explored Venezuela’s Caribbean coast. Caracas was established as a Spanish colonial center in 1567. The indigenous population was exploited for labor throughout the colonial era, and slaves were brought from Africa beginning in 1528. Simon Bolivar was born in Venezuela in 1783, and became the political and military leader of the regional struggle for independence from Spain. Venezuela declared independence in 1811, but the Spanish were not defeated until 1829. Bolivar abolished all slavery by decree in 1812. He is idolized by Venezuelans, and his visage appears in nearly every public area.

The German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and French botanist Aimé Bonpland studied nature and culture as they traveled throughout the Americas between 1799 and 1804. They collected the first botanical specimen of the rubber tree in Venezuela’s Orinoco Basin. The rubber boom that began in Venezuela’s southeastern tropical forests in the 1870s led to exploitation and territorial invasion of Ye’kuana, Yanomamo, and other indigenous groups by rubber barons. Prior to the 1920s, coffee cultivated in the coastal foothills remained the primary export product, and led to the early assimilation of indigenous populations. Foreign-owned companies began to develop Venezuela’s vast oil resources in the 1920s. A founding member of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), Venezuela nationalized its oil industry in 1975, resulting in rapid economic development but limited diversification. The petroleum industry currently accounts for one third of Venezuela’s gross domestic product. Approximately 90% of Venezuela’s crude oil exports go to the United States. This economic relationship produces a pronounced American influence on Venezuelan politics and culture, including entertainment and consumer commodities. Venezuelans take pride in a democratic two-party system that has existed since 1958. Steadily declining oil prices over the past 30 years have compromised the economy and political stability. Impacts of oil development on indigenous populations have been severe. Anthropologists Filadelfo Morales and Karl H. Schwerin have described a 40-year struggle between the oil industry and the Carina people.

Cultural Groups

There are three general cultural groups. Spanish-speaking descendents of colonial immigrants and more recent immigrants from Europe and other Latin American countries work in petroleum, manufacturing, commercial agriculture, mining, and service industries. They are predominantly Catholic. European languages like German and Italian are sometimes spoken within this group.

Roughly 2% of Venezuela’s people are indigenous descendents of those who migrated to the area before the Spanish. Most practice either pure or syncretic forms of Catholicism or Protestantism. Venezuela straddles the geographic ranges of the Carib, Arawak, Savila, and Chibcha linguistic families. Languages not assigned to a family (isolates) include Puinave, Hoti, Guahibo, and possibly Pume. Some of these people were originally foragers who did not plant gardens, but most practiced swidden (slash and burn) horticulture to grow manioc, maize (corn), bananas, and plantains as staple foods—supplemented by fishing, hunting, and collecting wild plants. Some groups like the Yanomamo continue this lifestyle. Other groups like the Bari and Makushi combine subsistence horticulture with commercial agriculture and wage labor. Groups like the Carina and Paraujano are more integrated into the dominant economy, live in towns, speak Spanish as well as their own language, and occasionally marry outside their ethnic group.

Regarding the third group, Venezuelan ethnohistorian Berta E. Perez describes the Aripaeno of Bolivar State as an example of descendents of slaves who overcame diverse African heritages and banded together in resistance to colonial slavery. Other Afro-Venezuelan groups are concentrated in the state of Miranda. Most speak a creolized Spanish.

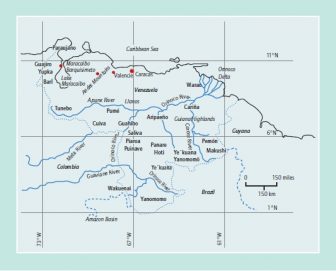

The population is unevenly distributed throughout five physiographic zones (Figure 1). The Andes and smaller forested mountain chains in the north separate the dry coast from the interior. Most people live in cities in the coastal plain or lower mountains. Sociologist Audrey James Schwartz’s 1975 study of barrios (impromptu neighborhoods) that sprawl up hillsides around Caracas challenged Oscar Lewis’s “culture of poverty” theory. Other groundbreaking urban ethnographies from the area include Lisa Redfield Peattie’s analyses of barrios in Ciudad Guayana and Margalit Berlin’s participant observation of factory seamstresses. Indigenous groups still exist in this area. Lawrence Craig Watson and Maria Barbara Watson-Franke have studied cultural change among rural Guajiro, including migration to barrios in Maracaibo City. In 1981, Antonio J. Lopez Epieyu published a dictionary of Guajiro language, still spoken by more than 300,000 people. Kenneth B. Ruddle has described change in agricultural strategies among the neighboring Yupka. On the basis of nearly 40 years of research, Venezuelan anthropologist Roberto Lizarralde has described change among the Bark Further east, Johannes Wilbert, Maria Matilde Suarez, and Basilio Mario de Barral have published ethnographic and linguistic accounts of the Warao of the Orinoco Delta.

South of the Andes Mountains, the llanos (plains) extend eastward and comprise one third of Venezuela’s territory. Extreme seasonal variation in rainfall creates savannah punctuated by scrub woodlands and gallery forests along rivers. Commercial agriculture includes cattle and rice. Large rivers have supported trade networks. Ted L. Gragson’s research shows how Pume along the Apure River rely heavily on fishing to supplement swidden horticulture. Anthony Leeds has explained Pume social organization using their cosmology. The Guahibo and Cuiva of this area were subsistence foragers, only recently transitioning to horticulture. The Cuiva have endured territorial invasion and genocide by ranchers.

In the east, the Guiana Highlands transition from savannah in the north to mountainous tropical forest in the south. The Pemon and Panare inhabit the transitional zone, where conflicts with mining and commercial agriculture continue. Most rivers flow into the Orinoco River, and are the lifeblood for groups like the Panare, the ethnographic subjects of Jean-Paul Dumont and Paul Henley. Mariano Gutierrez Salazar’s analysis of Pemon cosmology also documents the cultural importance of the area’s rivers and mountains. The southern tropical forests of the Guiana Highlands are home to the Piaroa, studied by Joanna O. Kaplan, Pedro J. Krislogo, and Stanford Zent. Venezuelan anthropologist Nelly Arvelo-Jimenez and French anthropologist Marc de Civrieux have conducted ethnographic studies of the Ye’kuana (Makiritare). Walter Coppens has documented invasions of Ye’kuana territory. The Yanomamo inhabit the southeastern forests bordering Brazil. The Wakuenai are found to the less mountainous southwest, where Venezuela’s rivers flow to the Amazon.

Issues in Venezuelan Anthropology

Anthropologists have influenced Venezuelan politics through social critique and activism. European colonists and their descendents relied primarily on Catholic missions to acculturate indigenous populations. Napolean Chagnon and others argued that missionaries negatively affected indigenous peoples.

Filadelfo Morales and Nelly Arvelo-Jimenez have criticized the government’s peasant and indigenous development policies since the 1960s as culturally and socially destructive. In 1989 indigenous peoples formed the Venezuelan National Indian Council (Consejo Nacional Indio de Venezuela). They achieved a political victory when many of their rights were codified in the revised national constitution in 1999.

The Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research (Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas) was established in 1952. Jacqueline Clarac de Briceno suggests this shifted Venezuelan anthropology from particularism to functionalism. Much of the new research was ecological. Stimulating one of the most important debates in anthropology, Chagnon used sociobiology to argue that the culturally isolated Yanomamo he studied exemplified a natural human tendency toward warfare, contradicting Rousseau’s proposition that “primitive” people are more peaceful. Timothy Asch’s films of Yanomamo violence are still widely used in anthropology classes. French Yanomamo ethnographer Jacques Lizot rejects the focus on violence. Marvin Harris’s proposal that Yanomamo warfare resulted from environmental protein scarcity stimulated extensive ecological research in Venezuela and elsewhere. Detailed analyses of Yanomamo nutrition and subsistence strategies by Lizot and Raymond B. Hames indicated no protein scarcity.

Paleoarchaeological research suggests that hunting populations had migrated into Venezuela by 11,000 years before present. The exact date of manioc (cassava) domestication is difficult to determine, but appears to have became a staple food by 4,000-3,000 years before present. Maize was domesticated in Mexico, and its cultivation spread eastward into South America. By analyzing carbon isotopes, Anna Roosevelt and her colleagues documented a shift from manioc to maize during the first millennium AD on the Orinoco floodplain. Many Venezuelan populations never fully adopted maize. The archaeological record indicates that beginning around 500 AD, a network of chiefdoms began to emerge in Venezuela, characterized by mound building, extensive trade networks, agricultural intensification, and irrigation. Excavations by Charles Spencer, Elsa Redmond, and Rafael A. Gasson in the western Llanos revealed variable house sizes, burials, and ceremonial plazas that indicate social stratification and centralized authority. Such chiefdoms still existed when the

Spanish arrived. Complex, hierarchical, bureaucratic state structures like the Inca and Classic Maya never developed in Venezuela. Ethnographic research by Anthony Leeds and David John Thomas suggests that flexible subsistence reduces the potential for centralized authority.

Past anthropologists generally considered Venezuelan cultural evolution to proceed from complex pre-Columbian societies to simpler forms after European influence. Neil L. Whitehead, Jonathan D. Hill, Gasson, and others argue that the situation is more complex, with new forms of social organization emerging as indigenous populations cooperated with, or resisted, colonialism. Debates about regional networks of power and trade systems continue, including how important they were, how they changed with European influence, and whether they will continue.

Archaeological and ethnohistorical data show more social complexity emerged in western Venezuela than the east before the Spanish arrived. In the early 1970s, Betty Meggers suggested that chiefdoms did not develop in Amazonia because of poor soils, and thus nature constrains culture. Roosevelt’s archaeological research in Venezuela and other Amazon areas, combined with ethnographic evidence from Emilio Moran, Jonathan Hill, Leslie Sponsel, and others, show flexibility in resource use can overcome many environmental limitations. A recent combination of archaeological and satellite data shows that past human activities created much of what was previously thought to be pristine Amazonian forest. Ecological studies from other areas of Venezuela include Stephen Beckerman’s analysis of Bari foraging, horticulture, kinship, and protein budgets, and Michael Jeffrey Paolisso’s research on Yupka time allocation.

The focus of anthropology in Venezuela, including ecological approaches, continues to shift from tribal to peasant and urban populations and issues of migration. The relevance of ethnohistorical analyses is increasing as people struggle to verify their ethnic ancestry. The biological and cultural effects of acculturation and migration represent an important current area of research. Further integration of ecological, biological, and cultural approaches will influence issues of health intervention and cultural survival, especially among formerly isolated groups like the Yanomamo.

References:

- Chagnon, N. (1983). Yanomamo: The fierce people. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Civrieux, J.-M. de. (1980). Watunna: An Orinoco creation cycle. San Francisco: North Point Press.

- Marquez, G. G. (1990). The general in his labyrinth. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- Pérez, B. (2000). Rethinking Venezuelan anthropology. Ethnohistory, 47, 513-533.

- Rouse, I., & Cruxent, J. M. (1963). Venezuelan archeology. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.