Technics can be a tool extending human body parts and senses or a combined physical system (man-tool, man-machine, man-natural process) created by a culture and utilizing human powers and external natural powers, structures, and systems for human cultural purposes. It is not important whether these systems and powers are predominantly animate or inanimate, natural or artificial, located inside or outside of humans. Technics may be human work with bare hands or with a tool, a factory production line, soil cultivation with a tractor or with animal power, corn growing, bread baking, or wine fermentation. There is one phenomenon differentiating technics from nature: the relevant structures and powers must establish a purposeful process that doesn’t work primarily for nature but for humans.

The term “technics” is usually understood objectively, with the emphasis placed upon the artificial element of the total technical system. It usually represents the “technical phenotype,” that is, the means of the technical operation: a tool, a machine, or an automatic system. The term “technology,” on the other hand, is understood as a process, as the functioning and operation of the technical systems.

Technics is a part of the human, antinatural culture and is rationally understandable only within this culture. Yet we must distinguish between two historical levels of technical development and between two basic development lines of technics: biotic and abiotic.

Hunting and gathering was the first stage of biotic technics development; its second stage, the Neolithic Revolution, was the first great technical revolution. The Neolithic period witnessed the arrival of almost all cultural plants and domestic animals. Basic procedures of food “manufacturing” and processing were also discovered during this time. Even the third stage of biotic technics development—the modern biotechnologies, cloning, and genetic manipulation— will hardly be able to surpass the Neolithic Revolution. Neolithic biotic technics, as a cultural channeling of a possibly multifunctional live system, was in harmony with the similarly anti-natural abiotic technics: it utilized the activities and characteristics of live systems but it didn’t interfere with their genetic information; it didn’t distort the natural biospheric information.

The abiotic technics production line, which is usually connected with the idea of technics itself, can be schematically described by the following terms: tool-machine-automation. This line developed in harmony with biotic technics up to the Industrial Revolution, that is, in harmony with the human skills and procedures utilizing the processes transforming live organisms.

The abiotic technics production line, which is usually connected with the idea of technics itself, can be schematically described by the following terms: tool-machine-automation. This line developed in harmony with biotic technics up to the Industrial Revolution, that is, in harmony with the human skills and procedures utilizing the processes transforming live organisms.

This difference between the two lines of technical development presents not only the hidden antinatural character of all technics but also the environmental advantages of the currently neglected biotic technics. Naturally, abiotic technics is more aggressive environmentally. Even though its energetic and functional bases were originally based in humans (humans activated and controlled tools), the original human functions in the instrumental anthropotechnical system (especially those energetic and kinetic ones) were transferred to the technical system from the beginning of mechanization. And this technical system doesn’t retrieve its energy from renewable resources but from nonrenewable fossil biomass.

The energetically much more thrifty biotic technics is mostly represented by live systems even today: microorganisms, cultural plants, domestic animals. Biotic technics remains, therefore, connected to the weakly integrating renewable energy of the Sun, even though it is forced to operate on behalf of man and culture.

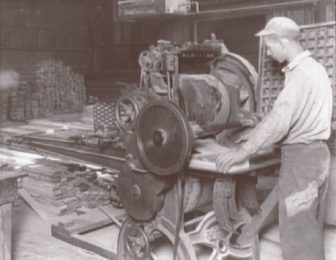

The first stage of the historical development of abiotic technics—instrumentalization—was characterized by slow improvements and differentiation in tools. It developed in harmony with biotic technics for millennia. Classic workmanship utilized natural human skills; it developed both the physical and intellectual characteristics of human beings, and its destructive effects on humans were negligible. Then, in an attempt to increase work productivity and utilize the power of cooperation, workmanship was divided into suboperations comparable with the later machine operations. This was the beginning of factories where human beings worked instead of machines.

The second stage of abiotic technics development— mechanization—was disseminated by the Industrial Revolution. Mechanical technics, which replaced artisans, brought the huge productive forces of science into the manufacturing process. Nevertheless, along with the increased productivity of human work, machines started a technological oppression of humans. From the very beginning, this technics tended to establish large machinery systems—factories. This was the basis for a strongly integrated global technosphere. Two large abiotic subsystems based on fossil fuels and spanning the whole planet appeared in the 20th century: (1) a predominantly stationary machinery subsystem (the power plant, electric power distribution networks, and other stationary mechanical technical devices), and (2) a predominantly mobile machinery subsystem (oil refineries, a worldwide network of oil product pumping stations, various vehicles, etc.).

The third stage of the abiotic productive technics development—automation, characterized by the establishment of fully artificial, technical systems— has disposed of the technological oppression of man but has narrowed the possible exercise of human labor in the labor market. Automated technics originates not only as a result of a high degree of scientific knowledge development. It also originates because natural biotic evolution has not utilized all the possible substance configurations in the environment of the Earth. The original, natural ecosystems, which were designated for all living things, were disturbed by technics, occupied, and transformed into an environment designated exclusively for humans.

The current postindustrial phase of abiotic technical creativity is based on an arrogant approach to nature. There is almost no respect for the values, integrity, and requirements of the natural evolution of the biosphere. Even though traditional biotic technologies are stilled used, and even though there are new technologies that are less aggressive toward nature, preserve energy, and produce minimum or no waste, the general character of the human approach to nature remains unchanged. This is more than just the dominance of abiotic technology; this is the dominance of the abiotic model for creating and satisfying human needs. The establishment of environmentally friendly manufacturing processes is up against environmentally reckless consumption. The technics-saturated human lifestyle also includes environmentally destructive consumer technics: private cars, household devices, hobby equipment, computers, TV sets, mobile phones, and so on.

The environmentally significant term technosphere describes a transnational system of functioning, reproduction, and evolution of technics. This spontaneously expanding and culturally determined system includes not only abiotic technics; it also includes the older and environmentally less aggressive biotic technics. Nevertheless, abiotic technics is dominant in the current technosphere. Its expansion, enlarging the cultural space, proceeds along many axes: vertically, horizontally, and transversally. New technical forms automatically occupy free social-cultural niches similar to the way plant and animal populations occupied their ecological niches.

Even though the evolution of technics and the technosphere is qualitatively different from the evolution of live systems and the biosphere, both fields are connected by many analogies and isomorphisms. For example, both evolutions need a comparatively free substance and energy; both need their own, internal information. A significant input of energy is able to include even rather large inanimate structures in the artificial technical systems, which are then capable of purposeful operation, specific cultural reproduction, and evolution.

The genetic information of technics, which has become a part of the social-spiritual culture, is created neither by an average human individual nor by the current world culture. It is created by a highly specialized element of the workforce in the technically most developed countries—by the technical intelligence. And this element can also complement it, change it, and develop it in the direction of the desirable technics. However, abiotic as well as biotic technics have coexisted with humanity from the very beginning; they have helped humans survive and to a certain extent they have been established by nature itself: by the position of humans in evolution, by humans’ special biological equipment, and by our need to defend our environmental niche even under undesirable natural conditions. Let’s hope that the pre-cultural natural-biological dependence of humans upon technics will not just reproduce itself again and again but will eventually force us to establish a sustainable form of the planetary technosphere.

References:

- Bernal, J. D. (1954). Science in history. London: Watts.

- Ellul, J. (1964). The technological society. New York: Vintage.

- Lilley, S. (1948). Men, machines and history. London: Cobbett.