Sumerian civilization began in the flood plains between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers. Deep beneath the land that now covers most of modern day Iraq lies the ancient country of Sumer where Sumerian civilization thrived. It covered approximately half of Mesopotamia. From 3500-2000 BC, this civilization flourished in the Mesopotamian land where the first cities began.

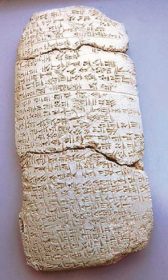

The Sumerians were the first civilized people to maintain a writing system called cuneiform (meaning curved lines). With this invention, the Sumerians were able to record literature, common laws, and business transactions and eventually created educational systems to teach cuneiform writing. The Sumerians gave the modern world a legacy of inventions, including agricultural and irrigation methods, weights and measures, the wheel, and the plow. They created the first city-state known for its architecture and its complex political, social, and economic structure that organized a legal system, labor practices, trade, and burial rites.

For thousands of years, cuneiform writing was the only writing system available to humans. At first, writing was developed to help govern trade and other business transactions. Later, people needed a way to identify themselves for business matters. Craftspeople developed pottery seals that, when rolled in moist clay, left behind a unique design or signature.

Writing quickly grew into a way of recording mythology, poetry, literature, mathematics, and historical events. For example, the legendary and much exaggerated tales of Gilgamesh were written in cuneiform. Gilgamesh was a mythical Sumerian ruler who possessed superhuman characteristics and engaged in fierce battles with ferocious animals. In fact, an epic tale of Gilgamesh tells of a great flood and is strikingly similar to the story of the flood in the Old Testament.

Cuneiform writing also enabled law codes, royal decrees, and court rulings to be recorded, preserved, and passed down through generations. The Sumerian King List, a chronology of legendary kings, is an historic example of this Sumerian legacy.

Writing was a skill that demanded great dedication and painstaking practice. Education became organized as children learned to read and write in cuneiform. The first schools resulted and children of only the wealthiest families attended them. At first, the purpose of school was to learn how to be scribes who could read and write cuneiform. However, in time, students began to study the sciences as well.

Writing was a skill that demanded great dedication and painstaking practice. Education became organized as children learned to read and write in cuneiform. The first schools resulted and children of only the wealthiest families attended them. At first, the purpose of school was to learn how to be scribes who could read and write cuneiform. However, in time, students began to study the sciences as well.

Despite the lack of adequate or consistent rainfall, Sumerian civilization was agriculturally based because the Sumerians developed an irrigation method. They dug canals that brought water to their farming fields. The Sumerians became skilled farmers, credited for inventing the plow to till the soil. Their chief crops were barley, wheat, and grains. They also grew peas, onions, lettuce, grapes, and figs. They raised sheep, cattle, and goats for milk, wool, and meat. They fished the abundant rivers and hunted an occasional antelope, gazelle, deer, or wild bull as a much-appreciated special treat.

As agricultural processes became more efficient, crops and livestock became plentiful. An array of specialized occupations emerged as some Sumerians were able to leave the farm and take up specialized crafts. Merchants, teachers, priests, physicians, musicians, poets, scribes, and tradesmen existed in addition to farmers and fishermen. Other Sumerians created weapons, cloth, and pottery. In fact, the first wheel ever invented was used as a pottery wheel. Further advances in the use and design of the wheel included turning it on its side and creating open spokes. This eventually created not only wheeled wagons but later in Mesopotamian history, chariots that would be used in battle.

As more people settled into Sumer, the need for buildings increased. Sumerians built homes, religious temples, and eventually, defense walls around their city-states to protect them from warring neighbors. Naturally, some citizens became skilled builders.

Because wood and stone were scarce and unsuitable for building, clay became the main building material. Sumerians made clay bricks that were cemented together with asphalt. Common citizens lived in small houses of two or three rooms with no windows. Wealthier families lived in two-story houses with the first floor used for servant quarters and meal preparations.

Not only did the Sumerians build homes, but their legacy includes impressive and elaborate buildings called ziggurats. These huge houses of religious worship were towers built with terraces. Each level was smaller than the one below and the walls inside were elaborately decorated.

The processes of irrigation and building required maintenance and cooperation of the Sumerian citizens. Rulers emerged to organize labor and send out traders to seek materials like wood and precious metals and stones, which were not readily available in Sumer.

All this change led to a growth in population and created a more complex lifestyle. The most populous areas were the city-states. The political structure of Sumerian civilization was different from other societies because their communities were fashioned into independent city-states that were originally organized around a temple and a priesthood. The earliest rulers of city-states may have been called an “en,” meaning “high priest.” They would have been a representative of the local god and responsible for managing the temple lands and the people entrusted to work on them. As societies grew more complex, a second office of leadership, called an ensi or “governor,” emerged to manage civic affairs such as law and order, commerce, trade, and military efforts. In time, the people democratically selected leaders to rule in times of war and peril. These leaders, called lugals, meaning “great man,” oversaw civil, military, and religious functions of the city. The office of lugal seemed to emerge at a time when defense walls were first constructed. It was customary for an elected ruler to step down and return to his place in society after a military crisis ended. Over time, however, the constant threat of war created a need for rulers to remain in power for longer periods of time. Eventually, rulers served for a lifetime, passing rule to their sons as successors to a king’s throne. As a state of dynasties had taken root, kings and royal families emerged.

Kings wrote and enforced local codes of law and, in Sumerian civilizations, legal matters were settled in courts of law. Three to four judges, who were often honorable men of the community, heard disputes. Much like the courts of today, evidence could be presented and witnesses gave sworn testimony. Perjury was punished by divine retribution because the gods would curse liars. However, decisions were not legally reversible because there was no process for legal appeal in Sumerian courts.

The most famous Sumerian city-states were Uruk, Ur, Eridu, Kish, Lagash, and Nipur. What we know today of these city-states comes from archaeological digs.

The glorious city of Ur, during the Third Dynasty of Ur dated at 2112-2004 BC, was an important center of Sumerian culture. Ur is identified in the Bible as the home of Abraham. The city’s proximity to the Persian Gulf made it an important seaport because southern Mesopotamia relied on trade for hardwoods, precious metals, and stones.

Archaeologist C. Leonard Wooley discovered what we know about Ur in the 1920s and 1930s. He found burial sites dating to 2600-2000 BC. The most common and simplistic sites had the deceased rest on their sides, as if they were asleep. The burial site contained a few personal possessions and ceramic bowls and jars for food and drink. Other more elaborate gravesites contained substantial quantities of goods, vehicles, and personal and household servants.

Although Woolley suggested that royal attendants drank poison and died willingly for their sire, the exact methods or reasons for these sacrifices are unknown. Sumerians buried their dead with possessions that the dead might want or need in the afterlife. For the wealthy or royal family members, this would also include servants and other members of the household staff.

After 1900 BC, Sumer would be overtaken by the Amorites and Guti, tribes from Elam. Sumer would never regain political domination and the whole of Mesopotamia would remain a warring land until the rise of Babylonia under Hammurabi, who would once again regain the region’s glory.

References:

- Crawford, H. (2004). Sumer and the Sumerians (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Landau, E. (1997). The Sumerians. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press.