In most Muslim societies, pioneering Sufi mysticism taught the principles of Islam in a simple way by committing its disciples to a special moral and social order with a specific worshipping recitation based on the Holy Qur’an and the Hadith (the Prophet’s sayings and deeds). “The Mawlawiyah (“Mevlevis” in Turkish), known to the West as the whirling dervishes, utilized the words and worldview of simple villagers, without using technical theological vocabulary, and thus they made divine truths accessible to those who were not literate or formally educated in theological Arabic or Persian.” The Sufi leaders observed a life of austerity, piety, and spiritual influence. The disciples believed in the miraculous actions and the blessing nature of the Sufi as a Walli (saint) who must be strictly obeyed. The North and East African Muslim Sheikh, the Maraboute of Senegal, and the other West African societies became a great spiritual force that often protected the poor and other powerless groups from the injustice of rulers. Sometimes, however, the Sufi would not strictly adhere to the formal shari’a (Islamic jurisprudence) in the striving to increase their non-Muslim followers.

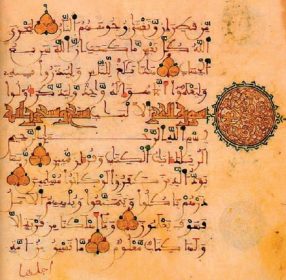

Since medieval times, many African and Asian indigenous cultures were incorporated into the Muslim Sufi tradition. Kings, chiefs, maharaja, or sultans believed in the supernatural powers of the Sufi Walli. In continuity with the ancient dancing parties of old deities in Africa, the turuq adopted necessary changes to ensure the monotheist meanings, ablution, and recitation of the Qur’an. In the post-Christian Nubia, the Sufi Wali or his successors assumed the privileges, high esteem, and miraculous expectations of the Christian saints to facilitate the difficulties of life for the Bedouins and the peasants. This helped Sufi teachings, rather than the formal shari’a, to merge with the old mythology and folklore.

Since medieval times, many African and Asian indigenous cultures were incorporated into the Muslim Sufi tradition. Kings, chiefs, maharaja, or sultans believed in the supernatural powers of the Sufi Walli. In continuity with the ancient dancing parties of old deities in Africa, the turuq adopted necessary changes to ensure the monotheist meanings, ablution, and recitation of the Qur’an. In the post-Christian Nubia, the Sufi Wali or his successors assumed the privileges, high esteem, and miraculous expectations of the Christian saints to facilitate the difficulties of life for the Bedouins and the peasants. This helped Sufi teachings, rather than the formal shari’a, to merge with the old mythology and folklore.

These accounts of early Islam indicate a unique liberalism of the Muslim community under the flexible teachings of the Sufi tradition. The Sufi orders often separated the spiritual leadership of society from the authority of the state. The rulers would not initiate state projects without Sufi advice. With this prestigious status, many Sufi leaders collaborated closely with the ruling groups to maintain stable social and religious relations with their believers. Many colonialist and post-independence governments encouraged the Sufi influence in Middle Eastern and African societies to avoid the engagement of Islamic jihad (holy war) in state politics. The Sufi leaderships accordingly enjoyed prestigious political and economic positions in collaboration with the governing groups.

References:

- Fluehr-Lobban, C. (2004). Islam societies in practice (2nd ed.). Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Hassan, Y. F. (1974). Tabaqat daif Allah (2nd ed.). Khartoum: University of Khartoum.