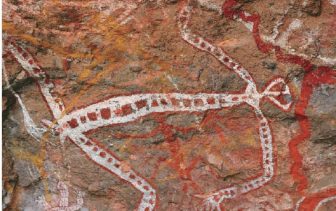

Rock art is painted, engraved, or scratched elements (signs, figures, writings) on rocky surfaces such as open-air rocks, caves, decorated menhir, boulders, and slabs. It may also include portable art and other forms of artistic representations of prehistoric populations. Often it is identified with cave art. The scientific study of rock art using archaeological methods is known as rupestrian archaeology.

Traditionally, engraving, bas-relief, graphics, and painting are considered the main genres of monumental rock art and mobile art (small artistic objects made of stone, bone, antler, or images on tools, everyday items, musical instruments, decorations, etc.). Both monumental and mobile rock art can be divided into two categories: animalistic (predominant in monumental art) and anthropomorphic (represented mainly in statuettes), which exist in three main forms: realistic (or naturalistic), ornamental, and gesture (singing).

The most striking examples of rock painting are found in the Pyrenees; complex polychromatic animal paintings decorate the caves at Lascaux, Montespan, and Trois Freres in France and Altamira in Spain. Such traits as three-dimensionality, perspective, proportion of items and their elements, and the impression of movement are typical of them. Sometimes connections between several images (animalistic and others) can be traced; a few may illustrate the development of a situation over time. Impressive scenes of hunting dominate in animalistic painting; it has become the background for a series of theories of the function of rock art in prehistoric culture. Human presence in rock art painting is usually conveyed by a series of signs symbolizing anthropogenic impact on the animal (images of human weapons, animal injuries, human hands on the animal images, etc.)

The most striking examples of rock painting are found in the Pyrenees; complex polychromatic animal paintings decorate the caves at Lascaux, Montespan, and Trois Freres in France and Altamira in Spain. Such traits as three-dimensionality, perspective, proportion of items and their elements, and the impression of movement are typical of them. Sometimes connections between several images (animalistic and others) can be traced; a few may illustrate the development of a situation over time. Impressive scenes of hunting dominate in animalistic painting; it has become the background for a series of theories of the function of rock art in prehistoric culture. Human presence in rock art painting is usually conveyed by a series of signs symbolizing anthropogenic impact on the animal (images of human weapons, animal injuries, human hands on the animal images, etc.)

Characteristic woman statuettes with exaggerated features of fertility (often called Paleolithic Venus) are a most peculiar form of mobile art. Their finds are connected mainly with Central Europe (Pavlov, Dolni Vestonice) and the Kostenki region of Russia and Middle Dnipro area of Ukraine (Mezin, Mezhirichi). They are made of soft stone (such as loess, sandstone, talc); most of them are schematic, with no portrait traits or any other personal features.

The first attempts at artistic activity date to the Early Paleolithic (Acheulean and Moustierian) period and are considered the result of experiencing the natural environment. Straight, curved, and wavy lines scratched or engraved on tubular bones, ribs, antlers, pebbles, and stone (mostly chalkstone and sandstone) are associated with this stage. Later, handprints and “macaroni” forms of artificial sign appear. The general development of rock art can be represented by the following chronology:

- 32,000-27,000 BC: few images of heads or front parts of animals;

- 26,000-22,000 BC: origin of sculpture and painting;

- 21,000-17.000 BC: gradual improvement of all genres;

- 16,000-10,000 BC: golden age of rock art;

- 10,000-6,000 BC: simplification and schematization of painting.

The general evolution of rock art was a gradual transition from simple painted or engraved lines, or representations of animal or human fragments, at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period, to complex polychromatic compositions at the end of the Upper Paleolithic period, to simplified schematic images during the Mesolithic period.

Rock art in different parts of Europe differs in artistic object, composition, and technique as well as forms and styles. The Franco-Cantabrian region is known for caves with realistic painting and engraving (Altamira, Lascaux, Nio, etc.). The Mediterranean (Italy, southern France, and southeastern Spain) is characterized by relatively more schematic images alongside numerous human handprints on cave walls (Balzi Rossi, Trois Freres, La Madelein, Font-de-Gaume). Some regard this as a unique area or as a special stage of rock art evolution. Eastern Europe (Central Europe and Siberia) is characterized by highly developed mobile art (including Paleolithic Venus) and bone ornamentals.

References:

- Bahn, P., & Rosenfeld, A. (Eds.). (1991). Rock art and prehistory. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Conkey, M. W., Soffer, O., Stratmann, D., & Jablonski, N. G. (Eds.). (1997). Beyond art: Pleistocene image and symbol. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences; Wattis symposium series in Anthropology, 23.

- Dowson, T. A. (1998). Rock art: Handmaiden to studies of cognitive evolution. In C. Renfrew & C. Scarre (Eds.), Cognition and material culture: The archaeology of symbolic storage (pp. 67-76). Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.