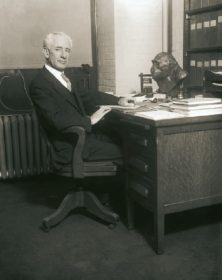

Robert Mearns Yerkes was an American psychobiologist who was among the most influential psychologists of the early 20th century. Although perhaps best known for his eugenic beliefs and role in the implementation of psychological tests for the United States Army in World War I, his most notable accomplishments were in nonhuman primate research. The Yerkes Primate Center is the world leader in research on great apes.

Yerkes was born on a farm outside of Breadysville, Pennsylvania, and described this setting as ideal. During a childhood battle with scarlet fever, which claimed the life of his younger sister, Yerkes developed a close relationship with the family doctor and was inspired to enter a career in medicine. The support of his uncle allowed Yerkes to attend Ursinus College in Pennsylvania. From there, he entered Harvard University for a second bachelor’s degree to help him prepare for graduate study. A suggestion by Josiah Royce, a philosophy professor and friend, was influential in Yerkes’s decision to study comparative psychology. Yerkes completed his doctorate in 1902, and in 1905, married Ada Watterson. The couple had two children. Yerkes remained at Harvard teaching comparative psychology until World War I.

While teaching, Yerkes involved himself in research dealing with the learning abilities of animals. In 1911, he developed the first multiple-choice test for animals.

The test consisted of rows of boxes and was designed to test abstract abilities. During subsequent testing, the animal had to remember which boxes contained food. Yerkes also collaborated with many of his distinguished colleagues. With John B. Watson, Yerkes developed an instrument to test color vision in animals using monochromatic light. With John D. Dodson, Yerkes developed the Yerkes-Dodson Law. The law states that an optimum level of motivation exists for every task. A U-shaped curve illustrates the relationship between arousal and performance of mice in a test involving compartmented boxes. Yerkes and Dodson found that excessive levels of motivation could be a deterrent for completing certain tasks. Other early research projects included studies on turtles, kittens, frogs, and various invertebrates. Early texts published by Yerkes included a review of mutant mice characteristics, The Dancing Mouse (1907), and a textbook, Introduction to Psychology (1911).

The test consisted of rows of boxes and was designed to test abstract abilities. During subsequent testing, the animal had to remember which boxes contained food. Yerkes also collaborated with many of his distinguished colleagues. With John B. Watson, Yerkes developed an instrument to test color vision in animals using monochromatic light. With John D. Dodson, Yerkes developed the Yerkes-Dodson Law. The law states that an optimum level of motivation exists for every task. A U-shaped curve illustrates the relationship between arousal and performance of mice in a test involving compartmented boxes. Yerkes and Dodson found that excessive levels of motivation could be a deterrent for completing certain tasks. Other early research projects included studies on turtles, kittens, frogs, and various invertebrates. Early texts published by Yerkes included a review of mutant mice characteristics, The Dancing Mouse (1907), and a textbook, Introduction to Psychology (1911).

Prior to World War I, Yerkes established himself as a leader in the study of human intelligence. In 1915, he revised the Stanford-Binet Intelligence scales that were designed to assess the cognitive and intellectual abilities of persons from age two to twenty-three. Yerkes was elected president of the American Psychological Association in 1916 and was chief of the Division of Psychology under the office of the United States Surgeon General in 1917.

A presidential proclamation in April 1917 involved Yerkes in the war effort. He became the chair of a committee charged with testing army recruits. A team of 40 psychologists including Henry Goddard, Lewis Ternman, and Walter Bingham worked under Yerkes, and together they developed the Army Alpha and Army Beta tests. The alpha test is a written measurement of intelligence, whereas the beta test is a pictorial test for the large numbers of illiterate recruits. Although not employed until late in the war, the tests were used to classify approximately 1.75 million men. Alpha test results were used to select the majority of commissioned war officers, as well as to discharge thousands of others deemed unfit to serve.

The army tests were a turning point for the developing field of human intelligence testing. Unlike the Stanford-Binet test, the alpha and beta tests could be administered to groups, decreasing the amount of time, personnel, and costs to the government. The widespread use of these tests lead to the popularization of public and private sector testing. Over time, however, the tests became extremely controversial as they were used to find (nonexistent) racial differences in intelligence. They were also used as proof of the supposed fall in overall intelligence of Americans.

Yerkes was against the idea of social Darwinism. Instead, he favored a eugenic view, believing that society could be improved through selective breeding for specific traits. His belief was solidified through studies of chimpanzee colonies at the Yale Laboratories.

Yerkes’s fascination with nonhuman primates began when he was a graduate student. Throughout his time at Harvard, he took several steps to develop a facility where studies on great apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans) could be conducted. Yerkes’s interest in primates lead him to purchase chimpanzees for himself, as well as spend time studying them in California and Cuba. Together with the president of Yale University, James Rowland Angell, a plan was developed to begin an Institute of Psychology at Yale. With funding from the Rockefeller and Carnegie Foundations, the Yale Laboratories for Primate Biology opened in 1930 in Orange Park, Florida. The institution was later named the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and is currently at Emory University in Atlanta.

Yerkes Primate Center was the first to demonstrate that chimpanzees could be successfully bred and studied in captivity. Research conducted at the center included the social and sexual behavior of chimpanzees as well as their learning and intellectual abilities. Yerkes’s primate research lead to a dozen books including Almost Human (1925) and Chimpanzees: A Laboratory Colony (1943), as well as coauthored texts such as Chimpanzee Intelligence and Its Vocal Expressions (1925) with B.W. Learned and The Great Apes (1929) with his wife, Ada. Yerkes published his autobiography in 1930 and retired from Yale University in 1944.

Yerkes served as chairman of the Research Information Service of the National Research Council from 1919-1924. He was also head of the council’s Commission on the Problems of Sex through 1947. In 1954, Yerkes was awarded the Gold Medal from the New York Zoological Society in recognition of his pioneering work in the field of psychobiology. He was a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as a member of the National Academy of Science, the American Philosophical Society, the Society of Mammalogists, and the American Society of Naturalists, of which he was elected president in 1938. Although Robert Mearns Yerkes died on February 3, 1956, at the age of 79, his contributions to the fields of animal behavior, learning, and cognition; captive breeding; intelligence testing; and psychology and psychobiology will live on for some time.

References:

- Dewsbury, D. A. (2000). Encyclopedia of psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Plucker, J. A. (2004). Robert Mearns Yerkes. Human intelligence: Historical influences, current controversies, teaching resources.

- M. Yerkes Dies: Psychologist, 79. (1956, February 5). New York Times.

- Strickland, B. B. (2001). Gale encyclopedia of psychology (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- Yerkes, R. M. (1926). The mind of a gorilla. Worchester, MA: Clark University.

- Yerkes, R. M. (1934). Modes of behavioral adaptation in chimpanzee to multiple-choice problems (Comparative psychology monographs). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Yerkes, R. M. (1982). Psychological examining in the United States army. Milwood, NY: Kraus Reprint.