The potlatch is a winter festival, with ceremonial feasts, where gifts and property are distributed to obtain or reassert a status, where prominent high caste families display crests, where names are given, where solidarity for war was made (in the past), and peace declared, where memorials are given and ancestors are honored. It was a place where “people played stick games in the evening” recounts Elizabeth Woody in her essay, “Tradition with a big ‘T.'” Over time the potlatch evolved through external influences, such as a new supernatural encounter, or introductions from surrounding and distant tribes, with European contact being the most dramatic change in ascendancy.

With the introduction of the European culture, a new wealth and merchandise system was instituted, which transformed the very format of the potlatch. Competitive potlatches rose to new heights of property distribution with most tribes, and more dramatically with the Southern Kwakiutl. This drew concern from the settlers and church leaders, leading to local governments petitioning for a ban to all potlatch activities in Canada.

Potlatch is a word derived from the “Chinook” trade jargon, meaning, “to give.” The potlatch existed prior to trade with the Chinooks. It existed in a clandestine manner in Canada while outlawed, and is growing in popularity even today. Will future pot-latches only be faint echoes of those of the past? Will today’s potlatches be the foundation for evolutionary growth in taking this festive occasion into a new modern realm? These are the questions to be answered by present and future generations.

The Potlatch Prior to European Contact

Potlatches were a way of life among the Northwest First People, and were carried on along the Pacific Coast of Alaska to Oregon. They created the impetus for daily activity; they were the economy, the basis for the flow of wealth, and the standard of the class system. Etiquette was not only observed in the potlatch, but in everyday life, as Stanley Walens reveals in Feasting with Cannibals, and was strictly enforced. This ceremony is more famously known through the First People from Southeast Alaska to British Columbia; in particular among the Tlingit, Haida, Bella Bella, Tsimshian, and Kwakiutl. Pot-latching was also practiced in the Washington and Oregon coastal villages of the Chinooks, Nootka, Salish, Lummi, and other surrounding tribal neighbors, as well as on the Bering Sea, along the Aleutian Islands and interior of Alaska, by the Aleuts, Athabascans, and Inupiat.

These are the peoples who would congregate, feast, and dance, while royally attired in regalia displaying their crests, which were passed down to them from their mother’s clan (for those of matriarchal societies) from time immemorial. This took the form of dancing and singing of ancient encounters, as in Pamela Rae Huteson’s Legends in Wood: Stories of the Totems, which give examples of encounters of transforming beings of the air and land, which could take off their coat of feathers or fur, and appear as human as any of “The People.” Culture bearers also brought these accounts through speeches, and even through puppetry during the weeklong celebrations. Secret Societies of Dog Eaters and Hamatsa Cannibal Dancers became infamous for their rituals. Those with higher rank utilized the potlatch to keep their standing, since castes were fluid, and it was easier to move down in rank than up.

Potlatch Preparation

The potlatch was a complex feast, even a symbolic feast such as a marriage or funeral, and could have underlying intentions or ambitions for the individual or clan sponsoring the celebration. There were five steps to take in preparing for a potlatch.

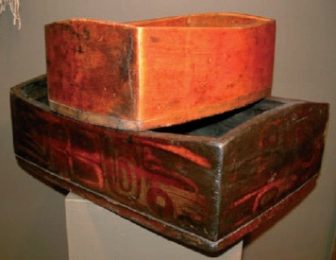

- Alliance would be made within the clan itself. Labor was required for the amassing of the great amounts of food required to feed large numbers of people for several days, and to choreograph the uses of the houses where distinct feasts would be held. Canoes, Chilkat blankets, bentwood boxes, and baskets were often commissioned and produced for the occasion.

- Alliances could come from other clans for labor and contributions. In tribes with two main clans, the opposite clan, George Thornton Emmons found, would “take over” the funeral processes and longhouse building for instance. They would also be paid for this service with gifts during the potlatch.

The late Thlawaa Thlingit Nation Council Elder, Eleanor Peratrovich, wearing tradition regalia during the entrance song of the Shinaku dancers

- Consideration would be made for invited guests. The larger the audience gathered to witness the event, the more direct was the reflection of the status and prestige of the sponsor and verification, to witness, the claims of property. Guests would be paid with gifts to witness the payment for the services rendered by the the opposite clan, and of status and property claims.

- The production of gifts, and the procurement of food (which also served as part of the gifts), was also very important. It could take years to accumulate presents to be distributed. The entire clan would participate in some aspect of gathering and producing. Totem poles and longhouses required forest materials of specific dimensions, and so these had to be sought out and retrieved.

- Regalia, including masks and/or other attire, had to be constructed for the performances, and the accompanying songs and dances had to be rehearsed. Dancers who performed incorrectly were regarded with great shame.

Drums sounded to announce the commencement of the potlatch. When the guests entered the long-house, at times paddles would appear first through the doorway opening. “The men folk came through first with the paddles. Others hid knives in their blankets, when they came in the house dancing. They did this to protect the women and babies,” explained Eleanor Peratrovich, Thlingit elder from Klawock, AK. Although a potlatch was a festive occasion, it could also be staged for revenge of an ancient wrong.

A formal speech would be made from the sponsor of the feast, usually the Chief. A declaration for the reason of the potlatch, as well as the history and rights of the clan would be made. Seating arrangements were strictly adhered to; placing a high caste person in a lower position was considered an insult. Several masters of ceremony could administer over the feast, ensuring the rank of speakers and performers. Food was served in bowls belonging to the clan, intricately carved with representations of stories, images, and property; the Tlingits called these precious items “at.oow.” Some bowls could be as long as a canoe, as in the case of the Wild Woman of the Woods bowls and the Woodworm dish of Klukwan. The feast alone could last half a day, requiring those in charge of the needs of the guests to provide special services of hospitality and attention. An extreme display of wealth in a competitive potlatch could involve eulachon oil dripping from the smoke hole into the fire, breaking copper shields or throwing them into the water (called drowning a copper), burning canoes, and even the killing of slaves.

Ban of the Potlatch

Inflation hit the Northwest Cultures as villagers obtained an easier source of prosperity, enabling them to access all ranks. For example, a traditional Chilkat or Raven’s Tail Blanket entailed a considerable amount of time to gather materials and weave, while a Hudson Bay Blanket was comparatively inexpensive, and became a new way to assign value to objects (for example, copper shields). One Kwakiutl Copper called “Making-the-House-Empty-of-Blankets” commanded 75,000 Hudson Bay Blankets as a purchase price. Prosperity increased as villages declined in numbers due to the ravages of European diseases, making it possible for new elite positions to open to those who previously were denied the opportunity to progress in class standing. Chiefs scrambled to prove their rights and position with abundant property displays (e.g., a successful sealing season could create enough wealth for a person to buy a coveted social position), as a breakdown of their socioeconomic cultural system encroached on their society’s power and control.

Competitive potlatches in Kwakiutl Country infuriated Canadian European settlers and church leaders like the Reverend and Mrs. A.J. Hall, who actively sought to quash the potlatch altogether. Additional misunderstanding of the “cannibal” performances, and other aspects of the potlatch process, culminated in the 1885 Canadian Law banning the potlatch. The enforcement of this law further contributed to the cultural genocide of the Canadian First Nations People. Aldona Jonaitis posits the following reasons for the decline of the potlatch: 1) Alterations in the structure of the fishing industry, 2) The depression, 3) Anglican persuasion, 4) Pentecostal evangelization, and 5) Lack of interest among young people.

Zealous arrests were made after potlatches, and the confiscated potlatch paraphernalia were sold to museums; which made William H. Halliday, Canadian government agent, consider the potlatch “dead.” The Elders lamented over this ban, while at the same time some Christian villages, like the Kispiox on the upper Skeena River, banned the potlatch and even posted their own Potlatch Prohibition Warning Notices.

This was the darkest period in potlatch history. Many Kwakiutls went underground with their potlatches, and incorporated giving with other celebrations.

The Potlatch Today

In 1951 the Potlatch Prohibition Law was lifted. Memorial and wedding potlatches were the first to resume in the villages; some had not held a potlatch for nearly a century. It was necessary to call on the Elders’ wisdom and memories for guidance to revive the singing and dancing of these ancient songs and dances. A revival of the Northwest culture had spread throughout the villages from Alaska to Washington as carvers and other new Northwest artists studied Bill Holm’s Northwest Coast Indian Art: an Analysis of Form to recapture an art form that was nearly extinct. Holm photographed and studied the old pieces; some may have even been used in pot-latches, of the Tlingit, Haida, Bella Bella, and Tsimshian art that was in museums all over the world. The popularity of Northwest Coastal art is increasing as well as totem pole restoration and replacement in the West Coast communities, such as Queen Charlotte Island in Canada and Prince of Wales Island in Alaska, where they now hold elaborate totem-pole-raising ceremonies and accompanying potlatches. The ceremonies that once lasted a week are now scheduled for 1 to 3 days, usually capping a weekend, thus accommodating the modern villager’s work schedule.

The potlatch is a festival tradition that has evolved from the special feast of the humble hunting/gathering tribes of the northwest, to the non-equalitarian tribes structuring castes, to the competitive potlatch wars. The potlatch may continue to evolve and birth new traditions; an example of this is “Celebration,” initiated by Sealaska in Juneau. This festival is a celebration of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian Cultures. Although not a potlatch per se, the potlatch dances and songs, native languages, and art come alive during this burgeoning festival held in Southeast Alaska since 1981. With more Northwest natives seeking to express their culture in ever expanding ways, the potlatch is thriving, and becoming a stronger influence in the lives of the new generations that are here, and those yet to come. “Gunulsh-Cheesh, Hoho” (Tlingit—Thank you, very much)

References:

- Colbert, M. (1942). Kutkos Chinook Tyee. Boston, MA: D.C. Heath and Company.

- Cole, D., & Chaikin, I. (1990). An iron hand upon the people: The law against the potlatch on the northwest coast. Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre; Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Dauenhouer, N. & Marks, R. (1990). Haa Tuwunaagu Yis, for Healing Our Spirit Tlingit Oratory. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Emmons, G. T. (1991). The TlingitIndians.F.de Laguna (Ed.). London and Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Holm, B. (1965). Northwest Coast Indian Art: An analysis of form. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Huteson, P. R. (2002). Legends in wood, stories of the totems. Tigard, OR: Greatland Classic Sales.

- Jonaitis, A. (Ed.). (1991). Chiefly feasts: The enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; New York: American Museum of Natural History.

- Thornton, M. V. (2003). Potlatch people: Indian lives and legends of British Columbia. Surrey: Hancock House Publisher LTD.; Blaine, WA: Hancock House Publishers.

- Walens, S. (1981). Feasting with cannibals: An essay on Kwakiutl cosmology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.