Are science and theology reconcilable in terms of evolution? As both an eminent geopaleontologist and cosmic mystic, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin presented a dynamic worldview. He argued that the human species does occupy a special place within a spiritual universe, and that humankind is evolving toward an Omega Point as the end goal of converging and involuting consciousness on this planet.

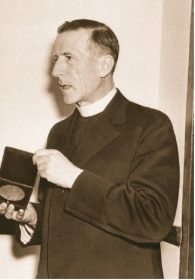

With his steadfast commitment to evidence of pervasive evolution, Teilhard, as natural scientist and Jesuit priest, became a very controversial figure within the Roman Catholic Church during the first half of the 20th century. Because of his bold interpretation of the human species within earth history and this cosmos, he was silenced by his religious superiors for taking an evolutionary stance at a time when this scientific theory was a serious threat to an entrenched orthodox theology. Going beyond Charles Darwin, Teilhard even maintained that evolution discloses the meaning, purpose, direction, and destiny of the human species within life, nature, and this universe.

As a geopaleontologist, Teilhard was very familiar with the rock and fossil evidence that substantiates evolution. As a Jesuit priest, he was acutely aware of the need for a meta-Christianity that would contribute to the survival and fulfillment of humankind on this planet, in terms of both science and faith. Sensitive to the existential predicament of the human species, with its awareness of endless space and certain death, Teilhard as visionary and futurist ultimately grounded his personal interpretation of evolution in process philosophy, natural theology, and cosmic mysticism that support panentheism (defined as belief that God and the World are in a creative relationship of progressive evolution toward a future synthesis in terms of the collective spirit of humankind).

Galileo Galilei endured house arrest and humiliation as a result of his claiming that the earth does in fact move through the universe, a scientific discovery that the aged astronomer was coerced into recanting by his dogmatic persecutor, Pope Urban VIII (formally Cardinal Maffeo Barberini), under the intolerant Jesuit inquisitor, Cardinal Robert Bellarmine.

As a direct result of the conservative standpoint taken by his religious superiors, Teilhard suffered both alienation and discouragement because he claimed that species (including the human animal) evolve throughout geological time, or else they become extinct; his daring evolutionism attacked fixity, essentialism, and biblical fundamentalism.

Discovering Evolution

As a child, Teilhard showed an interest in both natural science and religious mysticism. Sensitive to his beautiful Auvergne surroundings in France, and particularly drawn to the study of rocks, he found delight in a plowshare which he supposed was an enduring object, free from change and imperfection; however, after a storm, the youth discovered that his “genie of iron” had rusted. Later, Teilhard recounted how he threw himself on the ground and cried with the bitterest tears of his life. As a result of this devastating experience, the boy vowed seek his “one essential thing” beyond this imperfect world of matter and corruption. To be “most perfect,” as he put it, Teilhard entered the Jesuit society at the age of seventeen in order to serve God. At the same time, he intensified his interest in geology on the channel island of Jersey. Throughout his entire life, the scientist-priest would never abandon his love for science, concern about human evolution, and devotion to mystical theology— especially eschatology.

In 1905, as part of his Jesuit training, Teilhard found himself teaching at the Holy Family College in Cairo, Egypt. This three-year experience offered him the unique opportunity to do research in both geology and paleontology, expanding his knowledge of earth history. It also exposed him to a rich multiplicity of cultures, both past and present, that surely jarred him from European ethnocentrism. Following this teaching obligation, he then finished his theology studies at Hastings in England. During his stay in England Teilhard read Henri Bergson’s new, major book, Creative Evolution. This metaphysical work had an enormous influence on the scientist-priest, since it resulted in his lifelong commitment to evolution. It is worth emphasizing that it was not Darwin’s publications, but rather Bergson’s interpretation of evolution that convinced Teilhard that species, including the human animal, are mutable throughout organic history.

While on one of his field trips, Teilhard unfortunately became involved in the discovery of the controversial Piltdown skull, which was later determined to be a fraud. Although he had questioned the validity of this fossil evidence from the very beginning, one positive result of his involvement was that the young geologist and open-minded seminarian now became particularly interested in paleoanthropology as the science of fossil hominids.

After his stay in England, Teilhard returned to France where, during World War I, he was a stretcher bearer at the front lines. Remarkably, he emerged from his horrific experiences in the war trenches even more optimistic that evolution had been preparing the Earth for a new direction and final goal in terms of the spiritualization of the human layer of this planet. In fact, during the global war, Teilhard had several mystical experiences which he recorded for posterity. It was his emerging mysticism that would eventually allow him to reconcile science and theology within an evolutionary vision of the human future that was grounded in a spiritual reality.

In 1923, as a result of an invitation, Teilhard next found himself as a geologist participating in a scientific expedition into Inner Mongolia. A year in China gave the Jesuit a splendid opportunity to begin his career as a specialist in Chinese geology. It was during this time, while in the Ordos Desert, that Teilhard essayed “The Mass on the World,” a mystical account of his offering up of the entire world as Eucharist to a Supreme Being as the creator, sustainer, and ultimate destiny of an evolving universe. He expressed his dynamic Christology by viewing this planet as a part of an ongoing spiritual evolution, and continued to devote his life to synthesizing science and theology.

Upon returning to France, Teilhard ran into serious problems with the Roman Catholic Church because of his unorthodox beliefs. In Paris, he began giving public lectures on and teaching about evolution. This Jesuit priest was even bold enough to offer a personal interpretation of Original Sin in terms of cosmic evolution and the emergence of the human species in a dynamic but imperfect (unfinished) universe; he saw this cosmos as a cosmogenesis moving from chaos and evil toward order and perfection.

When a copy of Teilhard’s controversial essay fell into the hands of some of his superiors, he was censored by the Church: he could no longer teach or publish his own theological and philosophical views, and he was even exiled from France by the Jesuit order. Teilhard found himself back in China. There he wrote his first book, The Divine Milieu, a spiritual essay on the activities and passivities of the human being; Teilhard’s unorthodox book was denied publication.

When a copy of Teilhard’s controversial essay fell into the hands of some of his superiors, he was censored by the Church: he could no longer teach or publish his own theological and philosophical views, and he was even exiled from France by the Jesuit order. Teilhard found himself back in China. There he wrote his first book, The Divine Milieu, a spiritual essay on the activities and passivities of the human being; Teilhard’s unorthodox book was denied publication.

Fortuitously, Teilhard next found himself a member of the Cenozoic Laboratory at the Peking Union Medical College. Beginning in 1928, geologists and paleontologists excavated the sedimentary layers in the Western Hills near Zhoukoudian. At this site, the scientists discovered the so-called Peking man (Sinanthropuspekinensis), a fossil hominid dating back at least 350,000 years but now relegated to the Homo erectus phase of human evolution. Teilhard became world-known as a result of his popularizations of the Sinanthropes discovery, while he himself made major contributions to the geology of this site.

The Phenomenon of Man

Attemping to bring his scientific knowledge and religious commitments together, Teilhard began writing a synthesis of facts and beliefs aimed to demonstrate the special place held by the human species in a dynamic universe. Teilhard completed his major work, The Phenomenon of Man around 1940; in it, Teilhard steadfastly committed himself to the concept of organic evolution, but his work was again denied publication by the Vatican.

Teilhard argued that the evolving universe is a cosmogenesis. Essentially, the unity of this universe is grounded not in matter or energy but in spirit (the within-of-things or radial energy); thereby he gives priority to dynamic spirit rather than to atomic matter (the without-of-things or tangential energy). Moreover, Teilhard was a vitalist who saw the personalizing and spiritualizing cosmos as a product of an inner driving force manifesting itself from material atoms, through life forms, to reflective beings. He discerned a direction in the sweeping epic of this evolving universe, particularly with the emergence of humankind. However, his alleged cosmology is merely a planetology, since the scientist-priest focused his attention on this earth without any serious consideration of the billions of stars and, no doubt, countless planets that exist in those billions of galaxies.

Teilhard argued that the evolving universe is a cosmogenesis. Essentially, the unity of this universe is grounded not in matter or energy but in spirit (the within-of-things or radial energy); thereby he gives priority to dynamic spirit rather than to atomic matter (the without-of-things or tangential energy). Moreover, Teilhard was a vitalist who saw the personalizing and spiritualizing cosmos as a product of an inner driving force manifesting itself from material atoms, through life forms, to reflective beings. He discerned a direction in the sweeping epic of this evolving universe, particularly with the emergence of humankind. However, his alleged cosmology is merely a planetology, since the scientist-priest focused his attention on this earth without any serious consideration of the billions of stars and, no doubt, countless planets that exist in those billions of galaxies.

Of primary significance, Teilhard argued that the order in nature (as he saw it) reveals a pre-established plan as a result of a divine Designer, who is the transcendent God as the Center of creation or Person of persons; the direction in evolution is a result of the process law of complexity-consciousness. Teilhard was deeply interested in and concerned about the infinitely complex entity that would emerge in the distant future as the result of a spiritual synthesis, rather than occupying himself with the infinitely great and the infinitely small objects now in this universe.

For Teilhard, this cosmic law of increasing complexity and consciousness manifests itself from the inorganic atoms through organic species to the human person itself; or, this process law has resulted in the appearance of matter, then life, and finally thought. Evolution is the result of “directed chance” taking place on the finite sphericity of our Earth. Teilhard emphasized that evolution is converging and involuting around this globe: first through geogenesis, then through biogenesis, and now through noogenesis. The result is a geosphere surrounded by a biosphere, and now an emerging noosphere (or layer of human thought and its products) is enveloping the biosphere and geosphere. For this Jesuit priest, noogenesis is essentially a planetary and mystical Christogenesis.

The idea of a developing noosphere was also explored in the writings of the Russian scientist Vladimir I. Vernadsky (1863-1945). Very similar to Teilhard’s comprehensive and dynamic orientation, Vernadsky presented a holistic view of life on earth in his major 1926 work, The Biosphere.

Teilhard stressed that the process of evolution has not been a continuum: From time to time, evolution has crossed critical thresholds, resulting in the uniqueness of both life over matter and then thought over life. A person represents an incredible concentration of consciousness or spirit, resulting in the immortality of the human soul. Consequently, the Jesuit priest claimed that the human being is ontologically separated from the four great apes (orangutan, gorilla, chimpanzee, and bonobo).

For Teilhard, the ongoing spiritual development of our own species is converging and involuting toward an Omega Point as the end-goal or divine destiny of human evolution on this planet. His theism maintains that God-Omega is one, personal, actual, and transcendent. In the future, God-Omega and the Omega Point will unite, forming a mystical synthesis beyond space and time.

After The Phenomenon of Man was denied publication, Teilhard wrote Man’s Place in Nature: The Human Zoological Group (1950). This work is a more scientific statement of his interpretation of evolution. Unfortunately, the publication of Teilhard’s third book was also denied along with his request to teach in Paris.

While living in New York City, Teilhard twice had the opportunity to visit the fossil hominid sites in South Africa. On Easter Sunday, April 10, 1955, Teilhard died of a sudden stroke in New York City. He was buried at Saint Andrew’s on the Hudson, far removed from France. By the fall of that year, the first edition of The Phenomenon of Man was published in its author’s native language.

Teilhard was committed to science, evolution, and optimism despite his daring speculations and mystical orientation. Teilhard introduced into modern theology the concept of organic evolution at a time when this scientific theory was rejected by many who saw it as a threat. Unfortunately, in trying to reconcile science and theology, the Jesuit priest pleased no intellectual community.

Teilhard was an extraordinary human being of intelligence, sensitivity, and integrity. He experienced both the agony and ecstasy of time and change. His optimistic commitment to cosmic evolution flourished while he served on the blood-stained battlefield of a war-torn humanity, researched among the rocks and fossils of a remote past, and reflected in the deepest recesses of his profound soul on the meaning and purpose of human existence. As such, Teilhard himself exemplifies both the phenomenon of man and the ongoing quest for truth and wisdom in terms of a comprehensive anthropology.

References:

- Bergson, H. (1998/1907). Creative evolution. Mineola, NY: Dover. Birx, H. J. (1991). Interpreting evolution: Darwin & Teilhard de Chardin. Amherst: Prometheus Books.

- Miller, J. B. (Ed.). (2004). The epic of evolution: Science and religion in dialogue. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

- Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1965). Hymn of the universe. New York: Harper & Row.

- Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1966). Mans place in nature: The human zoological group. New York: Harper &Row.

- Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1975). The phenomenon of man (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row/Harper Colophn/Perennial Library.

- Teilhard de Chardin, P. (2001). The divine milieu (rev. ed.) New York: Harper & Row/HarperCollins/Perennial Classics.

- Walsh, J. E. (1996). Unraveling Piltdown: The science fraud of the century and its solution. NewYork: Random House.