Ancient Petra (Greek: “rock”), located in the southeast corner of modern Jordan, was the capital of the Nabataeans, and later, a provincial capital of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. Today, Petra is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Middle East.

Petra is situated in a valley bordered by mountain ridges on its east and west sides. The Siq, a narrow channel through the eastern mountain, forms the site’s traditional entrance and is today the gateway tourists use to visit the site. Because water is always a scarce resource in Jordan, Petra’s inhabitants managed the city’s water supply using a sophisticated system of channels and cisterns to deliver water from two nearby springs to the city’s cisterns.

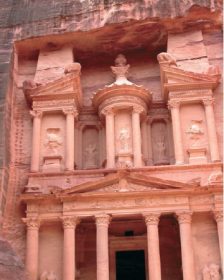

Archaeological evidence and Classical period historical sources help reconstruct Petra’s 9,000-year history. Small Neolithic settlements, such as Beidha, dot the region and attest to the region’s early agricultural history. Starting around 800 B.C.E. in the late Iron Age, the Edomites of Biblical fame established a village (Umm al-Biyara) on one of the high plateaus that guard the site. Petra saw a dramatic increase in settlement with the arrival of the Nabataeans from south Arabia in the late 4th century B.C.E. As the Nabataean capital, Petra was the center for an extensive spice trade that began in Arabia and stretched west to Palestine and north to Syria. Despite Pompey’s success in conquering Petra in 63 B.C.E., the Romans permitted the Nabataeans limited autonomy in their political affairs. Many of Petra’s architectural splendors were constructed at this time, namely, the tomb facades that line the city’s cliff faces such as al-Khazneh (the Treasury) and ad-Deir (the Monastery).

In 131 C.E., the emperor Trajan annexed Nabataea onto the Roman Empire, making Petra the capital of a new province, Arabia Petraea. Under the empire, Petra continued to flourish: a colonnaded street, a theater, and other civic and religious institutions were installed. The Empire’s conversion to Christianity occurred in 313, and the religion’s popularity soon spread to Petra, where multiple churches were established. Under the Byzantine Empire, Petra thrived as the seat of a bishopric, despite a devastating earthquake in 363 that destroyed half the city. A shift in trade routes and a second, even more devastating earthquake (in 551), led to a commercial decline and a dwindling population. Petra was eventually abandoned soon after Islam’s introduction into the region in the 7th century. Aside from a Crusader fortress on the city’s edge, settlement was limited to seasonal encampments of pastoral nomads until the early 20th century.

In 131 C.E., the emperor Trajan annexed Nabataea onto the Roman Empire, making Petra the capital of a new province, Arabia Petraea. Under the empire, Petra continued to flourish: a colonnaded street, a theater, and other civic and religious institutions were installed. The Empire’s conversion to Christianity occurred in 313, and the religion’s popularity soon spread to Petra, where multiple churches were established. Under the Byzantine Empire, Petra thrived as the seat of a bishopric, despite a devastating earthquake in 363 that destroyed half the city. A shift in trade routes and a second, even more devastating earthquake (in 551), led to a commercial decline and a dwindling population. Petra was eventually abandoned soon after Islam’s introduction into the region in the 7th century. Aside from a Crusader fortress on the city’s edge, settlement was limited to seasonal encampments of pastoral nomads until the early 20th century.

Petra was lost to Western visitors until 1812 when the Swiss explorer J. L. Burckhardt reintroduced the site to European audiences. Western explorers with more in-depth investigations of the ancient site followed Burckhardt. Scientific investigations of Petra began slowly after World War I, and increased rapidly after World War II, when Jordanian and foreign archaeological teams established projects throughout Petra. Sites were excavated not only to better understand the societies of their original architects, but also to rehabilitate buildings for presentation to public visitors. As a result, Petra attracts more than 1 million tourists a year, making it among the most visited antiquity sites in the Middle East.

References:

- Joukowsky, M. S. (Ed.) (2002). Petra: A royal city unearthed. Near Eastern Archaeology, 65(4).

- Markoe, G., et al. (2003). Petra rediscovered: Lost city of the Nabataeans. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- McKenzie, J. (1990). The architecture of Petra. London: Oxford University Press.