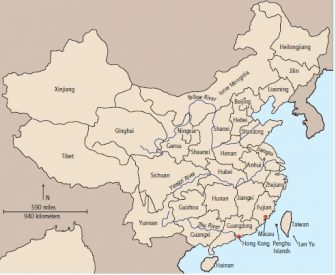

Any consideration of cultural diversity in the world, past and present, cannot ignore the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. The modern political units in this part of East Asia changed significantly during the 20th century. In 1949 Mao Zedong (Mao Tsetung) established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the Chinese mainland after defeating the Nationalist Party or Guomingdang (Kuomingtang) troops led by Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kaishek). At that time, Jiang established the Republic of China in the islands that constitute Taiwan. In 1997 Great Britain returned the islands in the territory of Hong Kong to the PRC, and in 1999, Portugal returned the territory of Macau to the PRC. Although publications tend to treat Chinese culture throughout these modern political units as homogeneous, there is significant regional variation in language, subsistence practices, housing, crafts, social organization, and ritual life. In addition there are numerous officially recognized ethnic groups living in these regions of East Asia. There is no doubt that such regional cultural variation first developed during the prehistoric period.

In addition, the total area cannot be ignored by virtue of its large size and huge population. At present the PRC has the largest population on earth, with over 1 billion people. There also is great physical diversity. The PRC is somewhat larger in size than the United States, with climatic zones spanning from cold temperate in the north to subtropical in the south. In the south, the favorable climate and beaches have made Hainan island a major tourist destination. Historically, northern China is often referred to as including those areas north of the Yangzi River (or Yangtze, also known as Chang Jiang). The largest river in northern China is the Yellow River (Huang He). Another major river in southern China is the Zhu (Pearl) River. Western and southwestern areas of the PRC are mountainous, while there are many fertile plains in the central and eastern portions. The Himalayan mountains, which include portions of Tibet, are the highest on earth. The striking limestone mountainous areas of the southwestern Chinese mainland are known for their beauty. There are several famous mountains in the PRC that were revered throughout history and in modern times by poets, painters, devout Buddhists and Daoists (Taoists), and lovers of nature. The mountainous islands of Taiwan lie in a subtropical zone. Early European explorers named these lush, beautiful islands Formosa, but the name is no longer used. Taibei (Taipei), situated in the north area of the main island, is densely populated. The east coast of the main island is known for its stunning views of the ocean. Typhoons, or large tropical storms, are common during the summer months in Taiwan and on the southern Chinese mainland.The time depth of human cultures in this large area of East Asia is of a scope that is rarely matched in other parts of the globe, including the Pleistocene period, later prehistoric periods with Neolithic cultures, up to a long historic period (including several dynasties). There is evidence for numerous turning points in human development, such as the transition to physically modern humans, the establishment of farming, the development of urbanism, the rise of early states, the invention of bronze metallurgy, and the invention of writing. Archaeological research, involving the study of material remains, is complemented by interpretation of rich and diverse early historical texts from the area. Many writers have noted that Chinese civilization is one of the oldest and most enduring civilizations in the world. Some cultural practices that developed early have continued to the present day, such as belief in the importance of ancestors and rituals involving food offerings.

During the 20th century, and through the onset of the 21st, there has been significant cultural change in China, especially in relation to economic development. For example, explosive economic development during the past two decades in the PRC has integrated formerly isolated areas with others and attracted labor from rural to urban settings. Differences in wealth between individuals have increased dramatically. Some traditional life-ways in rural areas are being abandoned in favor of urban customs. For example, traditional craft production (textiles, pottery, wooden implements) is declining. As economic development and cultural change takes place, however, people in the PRC and Taiwan remain justifiably proud of their rich cultural heritage.

Historic and Modern Cultural Diversity in the PRC and Taiwan

In the PRC, there are 56 officially recognized ethnic groups ( minzu). The largest of these is called the Han. The 55 ethnic minorities are often referred to as “nationalities,” emphasizing their different histories from that of the Han people. Ethnic identity here, as elsewhere, however, is a complex and changing phenomenon. Many ethnic minority peoples live in western and southwestern China, including areas bordering other modern countries. Modern political borders make it difficult to realize that peoples with similar cultural traditions live in neighboring countries of southeast Asia and other areas. Several provinces in the PRC have autonomous zones where one or more ethnic minority groups of people are concentrated. Ethnologists who specialize in ethnic minority cultures and languages tend to work at research institutes for that purpose, rather than in departments of anthropology.

In Taiwan there are several historically known aboriginal peoples who lived in the islands before the major migration of mainlanders in the first half of the 20th century. Most historical accounts identify nine ethnic groups, and today they comprise a small percentage of the population. Many aboriginal peoples adopted urban lifestyles at relatively early dates, given the rapid industrialization process in Taiwan. These indigenous peoples of Taiwan all once spoke languages belonging to the large Austronesian language family. There are linguistic similarities over a broad region, from tropical Asia to the Pacific islands. In Taiwan many professionals who research ethnic minority cultures regard themselves as anthropologists. A department of anthropology was established at a relatively early date at Taiwan National University in Taibei. It should be noted that there also were historically significant earlier migrations of Han mainlanders to Taiwan, especially during the 17th century. Many migrants came from Fujian province, directly across the Taiwan Straits.

In addition to cultural diversity in the area that comprises the PRC and Taiwan, there is tremendous linguistic diversity. For example, the official language in the PRC is Mandarin Chinese. Children from all ethnic backgrounds throughout the country learn the same Chinese characters. For many characters there are both simplified and complicated forms. In an effort to increase the literacy rate after 1949, the government of the PRC simplified many Chinese characters (an act that later generations of foreign students were grateful for). In Taiwan, however, people use the more complicated traditional characters. Throughout the PRC there is marked variation in spoken Chinese. There are several distinct dialects that generally vary by geographic area. The most marked is the difference between Mandarin Chinese and Cantonese, spoken by people in southernmost China, especially Hong Kong. Most northerners cannot understand Cantonese at all. Cantonese is the dominant form of spoken Chinese in many China towns in North America, since adventurous, early immigrants came primarily from southern, coastal areas. Within one single province, also, there can be several regional dialects. Many individuals have the ability to converse in their own dialect, or the national common dialect (referred to as putong hua), depending on the context.

Learning the Chinese language is a challenge for everyone. Educated people tend to recognize up to 5,000 characters. In addition, Chinese is a tonal language. Students must learn the proper tone (one of four) for a given sound in order to convey the proper meaning. In an effort to help foreign business people, tourists, and students know how to recognize and pronounce key words, the government of the PRC is providing increasingly more signs with the romanization of Chinese characters. The first romanization system widely used in North America is called Wade-Giles, and this system continues to be used in Taiwan. The PRC adopted the pinyin system of romanization. The difference can be seen in the spellings for the capital of the PRC, once referred to as Peking, and now more commonly referred to as Beijing.

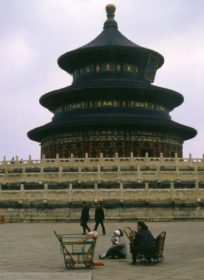

In many areas of the PRC where ethnic minority peoples live, children learn standard Chinese as well as their own languages. For example, in the northwestern province of Xinjiang, many children of the Uighur (or Uygur) minority group speak and write the Uighur language, a Turkic language. The Temple of Heaven (Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644), Beijing Source: Photograph courtesy of Anne P. Underhill.

Naxi people of Yunnan province had their own traditional written language using pictographs. Another distinct language within the PRC is Tibetan, spoken not only by people within Tibet but also in communities in neighboring areas. The Manchu language became more widely used during the Qing (Ching) dynasty (1644 to 1911 A.D.), when the emperors came from the Manchu ethnic group of northeast China.

In these areas of East Asia there is substantial regional variation in subsistence practices, housing, social organization, and ritual life. Subsistence systems in the eastern areas of the northern Chinese mainland were historically based on millet agriculture. Later rice became the preferred grain, and it has been grown in some relatively warm areas of northern China such as southern Shandong province. Relatively recent staple foods in northern China based on wheat and other grains include several varieties of noodles and steamed breads. A characteristic of the Central Plain (particularly in Henan province) and adjacent areas in the lower and middle Yellow River valley is loess, a type of fine, silty soil. In upland areas of the middle Yellow River valley, deposits of loess can be several meters thick. In parts of modern Shaanxi province, for example, cave homes are carved out of the deposits. For countless generations, farmers in several areas of the Yellow River valley have had to cope with extensive flooding caused by the extensive silt deposits.

Some inhabitants of northern and western areas of the Chinese mainland have had nomadic lifestyles. People of the Kazak ethnic group in Xinjiang have traditionally lived in yurts, moving seasonally to care for herds, commonly sheep and cows. Similarly, in Tibet, people have moved with the seasons to care for herds of animals such as sheep and yaks. They rely extensively on yaks for transporting goods as well as meat, milk and butter. There are also some Tibetan communities of settled agriculturalists. Arable land here is scarce, and barley is the main crop. Uighur farming families living in lowland areas of Xinjiang are also known for their beautiful embroidered and other colorful textiles.

In lowland areas of the south, paddy rice has been the dominant crop. The labor-intensive method of transplanting seems to have been in use since the Han dynasty, roughly two thousand years ago. House styles and craft production are adapted to the warmer, more aquatic environments of the area. Many varieties of bamboo are found here and are used for a variety of household items, as well as food. Fishing and travel by boat, on rivers as well as the sea, are important activities. Water buffalo are commonly used as draft animals in farming. In the southernmost, subtropical areas, there are several varieties of domesticated and wild plants that cannot grow in the north. In Taiwan, for example, the root crop taro is grown, and tropical fruits thrive such as mango and star fruit.

Two southerly areas of the PRC with exceptional cultural diversity are Yunnan and Guizhou provinces. Although ethnic minority peoples in these provinces tend to share similar customs with their Han neighbors with respect to subsistence practices and housing, there are marked differences in traditional clothing. A physical symbol of one’s social identity in many areas is the nature of textiles worn (materials, styles, designs), as well as ornaments. For instance the Miao people in Yunnan and Guizhou are known for the stunning silver headdresses and ornaments that women traditionally wear during festivals.

Similarly, several ethnic minority groups in Taiwan, such as the Ami in the scenic east coast area, have equally beautiful traditional textiles and ornaments. In addition the Yami people of Lan Yu (Orchid Island; once known as Botel Tobago) are famous for their brightly painted boats. These people enjoy chewing betel nut, a mild stimulant also popular in the Pacific region. Traditional Yami houses of wood are raised on wooden posts. In more than one southerly area traditional customs are being retained, in part for a growing tourism industry. Several museums are devoted to showcasing the rich ethnic minority cultures in many regions of the Chinese mainland and Taiwan.

There also has been considerable regional diversity with regard to social organization and ritual life. These aspects of culture do not neatly correspond with ethnic identity. Significant characteristics of historic and modern Han culture, and some ethnic minority cultures, in both northern and southern areas include the importance of extended family relations and tracing lineal descent through male ancestors. Traditional Confucian values that remain include respect for elders and authority figures. Confucius (551-479 B.C.) and his students also believed in the superiority of men over women, but attitudes about this issue have changed greatly since then. For many years, for example, women have run their own businesses, have had important positions in government, and have conducted important scientific research. Similarly, during the Warring States period (481-221 B.C.), an era of social upheaval and change, Daoist (Taoist) and other philosophers contemplated the social roles and responsibilities of individuals. There are Daoist temples on the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan from several eras devoted to various deities and immortals.

Many rituals among the Han and some ethnic minority groups are associated with ancestral veneration. During certain times of the year, which vary by region, families burn incense in honor of the deceased and place offerings of food and drink by graves. For the Han Chinese, white is the traditional color of clothing worn as a sign of mourning during funerals. Paper items such as symbolic money may be burnt as offerings for the deceased to use in the next world. In southern areas, temples have been particularly important loci of periodic rituals for lineage members.

Another form of ritual practice that seems to have a long antiquity in the Chinese mainland and insular areas is shamanism. There are practicing female shamans among the Puyuma of Taiwan, who aim to address spirits in order to cure people. Such research specialists have been known in other parts of East Asia as well, such as Korea.

Buddhism was first introduced to the Chinese mainland sometime during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D). The Han empire was of a scale comparable to the Roman empire. The Han state expanded to westerly regions for purposes of trade and defense. Over time, Buddhism was embraced by emperors and ordinary people alike. Buddhist temples and pagodas from several historical eras are common in the PRC and Taiwan. In the PRC, there are several stunning cave temples, some built on a massive scale. In the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, there also are many temples devoted to local Buddhist deities. Patrons may engage in certain rituals to seek information about their futures.

Diverse forms of social organization and ritual life are historically known among many ethnic minority peoples in both northerly and southerly areas. In traditional Tibetan societies for example, a practical adaptation in the past to the challenging natural environment (with limited agricultural land and the need for animal husbandry as well) was fraternal polyandry (brothers sharing a wife). Buddhism is the traditional religion of Tibet.

Northern areas of the PRC in particular also contain significant populations of Hui, or Muslim people. Islam was introduced to China during the Tang dynasty (618-907 A.D). Some of these people choose to wear distinctive headgear, while the beliefs of others can mainly be recognized by their avoidance of pork. Several cities throughout the PRC have active mosques. They are especially common in Xinjiang province, in areas where Uighur, Kazak, and other peoples live.

In the southwestern Chinese mainland there is great diversity in social organization and ritual life. Here, some ethnic minority groups have been known that are traditionally matrilineal, meaning that descent is traced through females. Women are the managers of these household economies, and the institution of marriage, as known among the Han people, does not exist.

During the 19th century, Christian missionaries from North America and Europe traveled throughout the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Some ethnic minority and Han peoples have continued to practice Christianity since then, and there are active churches in a number of areas.

Archaeology in the PRC and Taiwan

The field of archaeology is well developed in the PRC and Taiwan. There are numerous professional archaeologists conducting both rescue and research excavations in every region as well as graduate programs for training future generations of archaeologists. The practice of archaeology has deep personal meaning for these professionals, since there is great pride in uncovering evidence for the development of Chinese civilization. To many professionals, archaeology is a means of tracing evidence about one’s personal ancestors. At many universities in the PRC, archaeology is taught in departments of history. In Taiwan, many professionals regard archaeology as a subset of the field of anthropology. In both the PRC and Taiwan there are research institutes for archaeology as well. Archaeologists in all areas share common goals of using material remains to research issues such as change in technology, subsistence practices, social organization, and ritual life. Many also employ the rich and diverse texts from various eras of Chinese history to inform them about life in the past. There are numerous professional journals at the regional and national levels. Professional archaeologists devote considerable time to sharing their findings with the public, by writing books for the public and conducting interviews for television shows and newspaper articles. Archaeology is a priority for government officials; considerable funding is devoted to the construction and maintenance of new museums at the local, regional, and national levels.

Residents of the Chinese mainland and foreigners alike have long been fascinated with Chinese antiquity. At least as early as the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), scholars recorded information about the past. During the Song dynasty (960-1279 A.D.), scholars wrote catalogues describing ancient bronze ritual vessels. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, European travelers conveyed information to their fellow citizens about fascinating ancient sites that they had seen. Certain individuals, such as Aurel Stein, from Britain discovered key sites and inspired sinologists to conduct important research on historical texts and other materials. An established method for collecting and interpreting data about life in the past, including the crucial context of objects, not just the objects themselves, began to develop after the establishment of the field of geology in China. The creation of the Geological Survey of China was a turning point, and it also fostered an atmosphere of scientific collaboration among Chinese and foreign specialists.

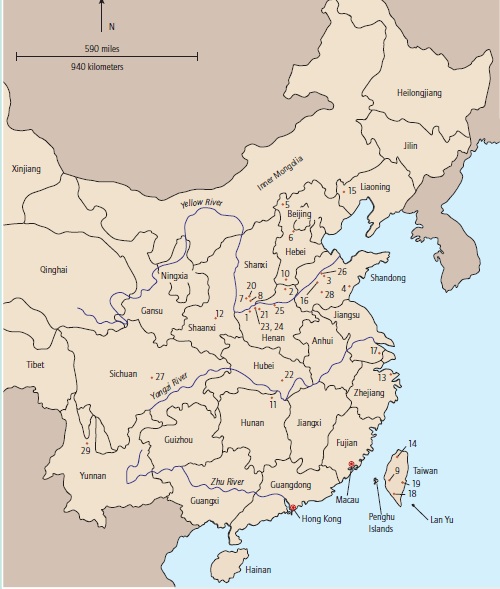

Soon a series of excavations took place, revealing a number of important ancient cultures. The first excavation in 1921 was directed by the Swedish geologist-turned-archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson, with an inter-national team, at a Neolithic (farming subsistence base) site called Yangshao in Henan province. Scholars later determined that the Yangshao culture spanned from ca. 50002800 B.C., with a wide distribution area in the middle Yellow River valley. Another extremely important series of early excavations took place at the late Shang period (ca. 1200-1046 B.C.) site of Anyang in northern Henan. Li Ji (Li Chi) directed a team of professional Chinese archaeologists that recovered not only important remains from the early Bronze Age capital site, but also large quantities of oracle bones, the earliest known writing in China. Subsequent teams of archaeologists discovered evidence for a late Neolithic culture in Shandong province called Longshan (ca. 2600-2000 B.C), on the basis of excavations at Chengziyai from 1930-1931 and at Liangchengzhen in 1936.

Key: 1, Yangshao; 2, Anyang; 3, Chengziyai; 4, Liangchengzhen; 5, Nihewan; 6, Zhoukoudian; 7, Dingcun; 8, Xiachuan; 9, Changpin; 10, Cishan; 11, Bashidang; 12, Jiangzhai; 13, Hemudu; 14, Dapenkeng; 15, Niuheliang; 16, Dawenkou; 17, Fuquanshan; 18, Fengbitou; 19, Beinan; 20, Taosi; 21, Wangchenggang; 22, Shijiahe; 23, Erlitou; 24, Yanshi; 25, Zhengzhou; 26, Daxinzhuang; 27, Sanxindui; 28, Lu; 29, early Dian.

Shortly before the PRC was founded in 1949, Li Ji (Li Chi) and some other archaeologists went to Taiwan and established the field of archaeology there. Some of the excavated remains from Anyang and Neolithic sites were moved to Taiwan. These scholars trained a new generation for archaeological research. Research in Taiwan has continued to focus on mainland sites as well as key sites in Taiwan. Meanwhile, the new government on the mainland began to establish research institutes for archaeology, departments within universities, museums, and professional journals.

Previously, Marxism was the dominant theoretical approach to interpreting archaeological remains in the PRC. For the last two decades especially, archaeologists have employed a variety of theoretical and methodological approaches. Since the early 1990s, the government of the PRC has allowed collaborative fieldwork projects with foreign archaeologists. These projects have included several systematic, regional survey projects and excavations at Paleolithic, Neolithic, and early Bronze Age sites. Chinese archaeologists have worked with numerous other professionals from Japan, Korea, Europe, Australia, Canada, the United States, and other areas. Archaeological fieldwork is taking place in every province of the PRC, and increasing numbers of local people from diverse backgrounds are participating. In addition there are Bureaus for the Management of Cultural Relics at the local, provincial, and national levels to monitor the research and protect sites.

The archaeologist who introduced ancient China to English speakers in North America and elsewhere is Zhang Guangzhi (Chang Kwang-Chih), known as K.C. Chang. Chang was widely admired by archaeologists in the PRC, Taiwan, and the West. His monumental syntheses and innovative, anthropological interpretations about the rise of civilization in ancient China, as well as description of his archaeological methods will remain as required reading for everyone. His voluminous articles and books, in both Chinese and English, span a period from 1953 to 1999.

Findings From the Paleolithic, Neolithic, and Early Bronze Age Periods

After the initial focus of archaeological fieldwork in the northern Chinese mainland, excavations and surveys have taken place in every region of the PRC and Taiwan. The extensive fieldwork and publications demonstrate that investigating the rise of Chinese civilization requires consideration of the diverse cultures from many areas. Also, archaeologists who wish to consider cross-cultural evidence for different kinds of social change in the past cannot ignore the rich data from the PRC and Taiwan.

Hundreds of Paleolithic sites have been discovered in several regions. These sites are providing information about topics such as the physical development of modern humans, adaptations to different kinds of environments during the Pleistocene period, and regional variation in stone tool technology. There are many challenges in interpreting sites on the Chinese mainland attributed to the Early Pleistocene period, over ca. 700,000 B.P. (before present, or years ago). There have been controversies about dating of remains, integrity of the stratigraphic deposits (i.e., whether there has been disturbance), and identification of artifacts (versus objects formed by natural processes). Currently it appears that some of the earliest stages in the physical and cultural development of hominids took place on the Chinese mainland in addition to Africa. A handful of sites appear to have dates older than 1 million years ago, including more than one locality in the Nihewan Basin in northwestern Hebei province.

In contrast there are numerous sites from the Middle Pleistocene period on the Chinese mainland. The most famous is Zhoukoudian (Chou-k’ou-tien), near Beijing, discovered in 1922 by Johan Andersson, with the main deposits dating ca. 500,000 B.P. Subsequent excavations by Pei Wenzhong and others yielded abundant remains of Homo erectus that were referred to as “Peking Man.” Tragically, these remains were lost during World War II. Important new research continues to take place at the site, where caves yielding skeletal remains, remains of animals such as hyenas and saber-toothed tigers, and stone tools indicative of a Lower Paleolithic technology have been found. Zhoukoudian is one of the richest Paleolithic sites in the world, with evidence for over 200,000 years of occupation. The key institution conducting excavations at Paleolithic sites in the PRC is called the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Physical Anthropology (IVPP). Other comparable sites yielding Homo erectus remains and/or stone tools exhibiting a Lower Paleolithic technology have been found in Shaanxi, Shanxi, Liaoning, Guizhou, Yunnan, and other provinces. It is clear that Homo erectus populations were able to adapt to a wide variety of environmental regions in both northern and southern China.

Late Pleistocene sites, both open air and cave sites, have been found in an equally wide area. These include sites (ca. 200,000-40,000 B.P.) with early Homo sapien’s skeletal remains and stone tools exhibiting a Middle Paleolithic technology. One key site where archaic Homo sapiens remains and stone tools were recovered is Dingcun in southern Shanxi. Later sites, after ca. 40,000 B.P., have remains of fully modern humans (Homo sapiens) and an Upper Paleolithic stone tool technology.

A clear trend evident from sites on the Chinese mainland, as elsewhere, is diversification of stone tool technology. There was increasingly more specialization of tool forms and more efficient use of stone. Microlithic tools have been found in several sites. Sites such as Xiachuan in southwestern Shanxi yielded a variety of blades, scrapers, and points. Current research focuses on delineating regional variation in subsistence practices (hunting, gathering, shelter) and tool technology. The Upper Cave at Zhoukoudian (ca. 15,000 B.P.) is important for what may be the earliest evidence for mortuary rites in China. It appears that mourners spread hematite over the bodies. Archaeologists also found a variety of bone and antler tools at Late Pleistocene sites, and ornamental items of both stone and bone. The Changpin (Ch’angpin) site on the east coast of Taiwan probably dates to ca. 15,000-20,000 B.P. Preliminary scientific analyses indicate that the earliest human remains here date to ca. 20,000 B.P.

Numerous prehistoric cultures from the Holocene period after ca. 7000 B.C. have been identified all over the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. There is evidence for diversity in regional cultural traditions, but unity as well. Research shows that northern China was a locus of early millet cultivation. Sites from the Peilgang culture such as Cishan in southern Hebei yielded domesticated millet ca. 6200-5000 B.C. More research has taken place in the south, where early sites with wet rice cultivation have been found in the central and lower Yangzi river valley. At Pengtoushan culture sites, ca. 7000-5200 B.C., such as Bashidang in Hunan, large quantities of rice and pile dwellings were discovered.

Later Neolithic cultures based on farming (ca. 5500-4000 B.C.) become more diversified, with more distinct traditions of subsistence practices, craft production, and mortuary practices. Some Yangshao sites, such as Jiangzhai in Shaanxi, reveal community planning and more than one house style. In the Yellow River valley at this time, multiple burials were more common. Waterlogged deposits at the Hemudu site in the lower Yangzi river valley revealed a wide variety of craft goods, including a lacquer container, a boat oar, reed mats, finely incised bone artifacts, and bone whistles. Meanwhile, people in subtropical Taiwan from the Dapenkeng (Ta-p’en-k’eng) culture, after ca. 5000 B.C., may have grown taro like their descendants.

Significant social changes took place during the late Neolithic period in more than one area of the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. Differentiation in housing and burials indicate that social ranking emerged during the period ca. 4000-2600 B.C. Greater quantities of prestige goods, such as jade items and labor-intensive pottery vessels, were produced. On a regional scale, archaeological surveys reveal the emergence of settlement hierarchies. Public rituals occurred on several large sites, most notably at the Hongshan culture site of Niuheliang in western Liaoning province. A minority of large, rich graves is a characteristic of several sites, such as Dawenkou (Dawenkou culture, Shandong province) and Fuquanshan (Liangzhu culture, near Shanghai).

Travel by boat must have been common on the open seas in addition to rivers and lakes. The Penghu (P’eng-hu) islands between Taiwan and Fujian were first occupied as early as ca. 3000-2500 B.C. On the southeast mainland and on Taiwan, successful ways of life continued for hundreds of years; there were similar late Neolithic cultures, ca. 2000 B.C. and later. Another important Neolithic culture of Taiwan is the Fengbitou (Feng-p’i-t’ou) culture, dating ca. 1500-500 B.C. The Beinan (Pei-nan) slate burials of the east coast (ca. 2500-800 B.C.) have fine jade ornaments and dental evidence for chewing betel nuts, like later peoples in southern Taiwan.

In several areas of the Yellow River and Yangzi River valleys, regional systems of social organization became larger and more structurally complex during the Longshan period (ca. 2600-1900 B.C). Large settlements, some surrounded by earthen walls, appear to have been regional centers. This pattern, coupled with increased nucleation of regional populations, indicates the beginnings of the process of urbanization. Key sites from this period include Taosi, Wangchenggang, Liangchengzhen, and Shijiahe. Even more labor-intensive forms of prestige goods were produced, and relatively few people had access to them. The most striking example is the famous “eggshell” black pottery stemmed cups, literally the thickness of an eggshell. More research on the economic bases of these regional polities should provide evidence for loci of production and intercommunity exchange of goods, as well as the nature of leadership.

The earliest known state period represented at the Erlitou site in west-central Henan dates to ca. 1800-1600 B.C. During the Erlitou period, metallurgy was mastered. At this time elites preferred to bury bronze drinking and eating vessels with the deceased, rather than fine ceramic wares as previously. During later phases of the early Bronze Age, a number of states developed. The early Shang state became powerful ca. 1600 B.C., and the state expanded over time, with major centers at Yanshi and Zhengzhou in west-central Henan, Daxinzhuang in western Shandong, and the late Shang site of Anyang after ca. 1200 B.C. in northern Henan.

The presence of powerful rulers at these Erlitou and Shang period sites is clear, from abundant skeletal evidence for human sacrifice, bronze weapons, foundations of large palaces, and graves containing hundreds of prestige goods (especially bronze vessels and jades). The most notable is the tomb of Fu Hao, the consort of a late Shang king, known from the oracle bone inscriptions as a military leader in her own right. During the late Shang period, ritual duties, such as making sacrifices of humans and animals to powerful ancestors, formed a key component of leadership.

Meanwhile, powerful states had emerged in other parts of the Chinese mainland. At Sanxingdui in Sichuan, archaeologists were stunned to find evidence of an independent, and very different, tradition of metallurgy. They excavated ritual pits containing huge bronze heads and entire figures, along with numerous elephant ivory tusks. Archaeologists also found a walled settlement area, indicating a regional center of a state contemporary with the earlier Shang period in Henan province.

The late Shang oracle bone records indicate that warfare was a major concern of kings. Eventually the Shang state was conquered by peoples from further west in the Yellow River valley, establishing the Western Zhou dynasty. The Western Zhou state (1046-771 B.C.) controlled a wide area of the Yellow River valley by means of strong local administrative units. Several Western Zhou sites have been found in southern Shaanxi. Many of the ritual elements of kingship were continued from the Shang, such as burying large quantities of goods with deceased elites who were about to become powerful ancestors. There also is abundant archaeological evidence for smaller, independent states during the Western Zhou period, such as the Yan state located near Beijing.

Eventually, the large Western Zhou state centered in Shaanxi began to disintegrate. During the subsequent Eastern Zhou period (including the Spring and Autumn and Warring States phases, 771-221 B.C.), different states in both north and south China vied for power. Warfare increased in intensity and scale as well as frequency. The period also is known for its technological innovation (including the more widespread use of iron), as different states competed to produce new forms of weapons and prestige goods. During these later phases of the early Bronze Age, increasingly diverse forms of written records were employed. Philosophers and teachers, such as Confucius from the state of Lu in modern Qufu, contemplated the tumultuous era in which they lived, advocating virtuous behavior and social harmony. Contemporary sites from the Chu state in Hubei and Hunan provinces have yielded exquisite wooden and lacquer artifacts.

Meanwhile, an independent Bronze Age culture emerged in Yunnan province. The earliest phases of the Dian culture in western Yunnan developed during the 11th century B.C., and spread to central Yunnan during later phases until the 1st century A.D.

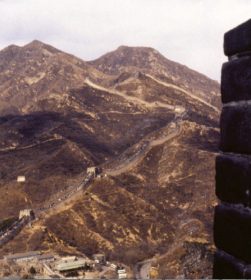

Eventually in 221 B.C., the Qin state conquered all the other warring states, and China’s first empire was born. The emperor Qin Shihuangdi attempted to maintain his power by beginning the construction of the Great Wall. Later generations of rulers would order the construction of new sections of the wall. The empire did not last long, as the emperor died in 206 B.C. Parts of his astonishing mausoleum near Xian city have been excavated, yielding the famous pits where hundreds of life-sized terracotta soldiers were discovered—evidently modeled after real people who served the emperor. The location of his tomb is known but remains unexcavated.

For consistency, this essay first cites Chinese names using the pinyin romanization system established in the PRC. In parentheses it provides some equivalent words using the Wade-Giles romanization system that was formerly more common in North America and that has been used in Taiwan. It presents surnames first (such as “Mao”), the convention in both the PRC and Taiwan. References at the end of this essay are listed according to the North American system.

References:

- Cauquelin, J. (2003). The Aborigines of Taiwan. London: Routledge/Curzon.

- Chang, K. C. (1986). The archaeology of ancient China. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Cheng-hwa, T. (1992). Archaeology of the P’eng-hu Islands. Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, Special Publications, No. 95.

- Taipei: Taiwan, R.O.C. Debaine-Francfort, C. (1999). The search for ancient China. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Goldstein,M. (1992). When brothers share a wife. In E. Angeloni (Ed.), Anthropology 92/93

- Fifteenth Edition (pp. 109-112). Guilford, CT: Dushkin.

- Harrell, S. (Ed.) (2001). Ways of being ethnic in southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Liu, L., & Chen, X. (2003). Early state formation in China. London: Duckworth Press.

- Murowchick, R. (Ed.) (1994). Cradles of civilization. China. Ancient culture, modern land. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. Stark, M. (Ed.) (in press). Archaeology of Asia. Blackwell Publishers.

- Underhill, A. (2002). Craft Production and Social Change in Northern China. New York: Kluwer Academic Press.