Few subjects captured the imagination of early European explorers more than the seafaring exploits of Pacific islanders. In 1768, the French explorer, Bougainville, dubbed Samoa “The Navigators’ Islands,” and the British captain, James Cook, noted that Polynesian canoes were often as fast and maneuver-able as his ships. Subsequent commentators, particularly within the anthropological community, have retained their predecessors’ fascination.

Western views of oceanic seafaring abilities have shifted several times. Through the mid-20th century, indigenous traditions of voyaging, exploration, migration, and settlement were taken quite literally. In 1957, Andrew Sharp argued that, unless aided by instruments, human beings couldn’t navigate successfully over long distances. Therefore, colonization of new islands was almost certainly the result of accidental drift voyages by sailors blown off course or forced, against their will, out to sea.

Sharp’s conclusions were challenged by the pioneering ethnographic work of Thomas Gladwin (1970) on Puluwat in Micronesia and David Lewis’s more wide-ranging survey. They and others have documented voyages of hundreds of miles with accuracy comparable to that of Western mariners aided by modern instruments, and they carefully described indigenous navigational techniques.

A second line of evidence casting doubt on Sharp’s drift voyage argument is provided by the direction of settlement: from west to east, against the prevailing winds. Computer simulations comparing winds and currents with the geographical and cultural relationships of various islands and archipelagoes have demonstrated that oceanic exploration and settlement could not have been a result of accidental drift, but must have eventuated primarily from purposeful voyaging by skilled navigators.

The final line of evidence supporting the proficiency of oceanic navigators comes from experimental voyages with replicas of traditional canoes, using traditional navigational techniques. Hokule’a, a performance-accurate replica of a Hawaiian double-hulled voyaging canoe, built with modern materials but to traditional design, was sailed successfully through almost all of Polynesia. In the aftermath of Hokule’a’s success, other voyaging canoes were built in the Cook Islands of Aotearoa (New Zealand), and elsewhere in Polynesia. In 1993, the Hawaiian Voyaging Society launched Hawai’iloa, a voyaging canoe constructed out of natural materials. Hawai’iloa, like its predecessors, has now logged thousands of miles of deep-sea inter-island travel. Meanwhile, many indigenous communities are working to revive their seafaring heritage. Noteworthy in this regard are the efforts of the Vaka Taumako Project in the eastern Solomon Islands.

The final line of evidence supporting the proficiency of oceanic navigators comes from experimental voyages with replicas of traditional canoes, using traditional navigational techniques. Hokule’a, a performance-accurate replica of a Hawaiian double-hulled voyaging canoe, built with modern materials but to traditional design, was sailed successfully through almost all of Polynesia. In the aftermath of Hokule’a’s success, other voyaging canoes were built in the Cook Islands of Aotearoa (New Zealand), and elsewhere in Polynesia. In 1993, the Hawaiian Voyaging Society launched Hawai’iloa, a voyaging canoe constructed out of natural materials. Hawai’iloa, like its predecessors, has now logged thousands of miles of deep-sea inter-island travel. Meanwhile, many indigenous communities are working to revive their seafaring heritage. Noteworthy in this regard are the efforts of the Vaka Taumako Project in the eastern Solomon Islands.

Canoe Design

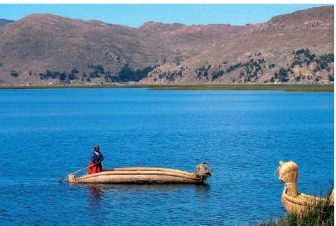

Most commonly, Pacific mariners used single-outrigger canoes ranging from small vessels paddled by one or two men (or occasionally women) for coastal travel and inshore fishing to vessels that might approach 100 feet in length and rival European sailing ships for speed. In Micronesia, parts of Melanesia, and most Polynesian outliers, canoes are designed with an interchangeable bow and stern. The vessel is tacked (i.e., has its course changed) by moving the sail from one end to the other, thereby always keeping the outrigger upwind. In most of Polynesia, bow and stern are distinct; the outrigger is always kept to the same side (most often, to port, i.e., the left side of the ship); and the canoe is sometimes sailed with the outrigger in the craft’s lee (sheltered side).

The most imposing of Pacific voyaging canoes were the great double-hulled vessels of the Polynesian heartland. Such canoes have been reported from Aotearoa and Tonga to Rotuma, Tuvalu, and north to Hawai’i. Voyaging canoes could cover more than 100 miles per day with a favorable wind. The outrigger or double-hull design provides resistance to leeway drift without the need for a deep keel, which is a hazard when sailing among shallow reefs. More specialized developments included the New Zealand Maori’s impressive single-hulled, outrigger-less canoes. For an inventory of Pacific Islanders’ canoe construction and design, Haddon and Hornell’s encyclopedic treatment remains unparalleled.

Navigation

Most Pacific navigators rely mainly on the movements of celestial bodies. Ideally, the navigator identifies a star that rises directly over his target island and points the canoe’s bow toward that star. When the first star rises too high, he turns his attention to another following approximately the same trajectory. If a sequence of stars does not rise or set directly over the target island, the navigator sets off the bow at an appropriate angle while compensating for wind and current.

Most problematic is detecting currents on the open sea. A capable navigator knows the prevailing currents. He confirms their direction and speed while near the point of embarkation or when sailing over shallow reefs. Some navigators assert that by feeling wind velocity and seeing or feeling the condition of the sea, they can even discern a current’s direction in deep water, far from land.

The navigator may gauge latitude by identifying zenith stars or by observing the altitude at which specific stars rise and set. Longitude must be estimated by dead reckoning—the navigator fixes the canoe’s position by estimating the vessel’s speed, direction, and how long it has been at sea. Since he must keep a running total of the vessel’s progress at all times, he cannot sleep, other than occasional brief naps, even on a lengthy journey.

When stars are not visible, the navigator relies upon prevailing wind and wave patterns. In addition, long-distance voyagers may have employed “latitude sailing”—sailing to the latitude of the target island but well to windward, then making landfall by running downwind. They minimized their risk by island hopping, thereby breaking lengthy journeys into shorter segments. Wherever possible, they aimed for groups of islands rather than isolated targets.

Navigators usually attempt to make landfall during daylight. Before land is visible, its presence may be indicated by birds that roost on shore but feed at sea during the day. Reflected waves are shaped differently from waves produced directly by the wind and can, at times, be felt at distances of more than twenty miles from land. Clouds tend to accumulate around the peaks of high islands, indicating their presence; and a greenish tint to clouds may reveal the presence of an atoll that cannot be seen from a canoe.

References:

- Feinberg, R. (Ed.). (1995). Seafaring in the contemporary Pacific Islands: Studies in continuity and change. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois

- University Press. Finney, B. (2003). Sailing in the wake of the ancestors: Reviving Polynesian voyaging. Honolulu, HI:

- Bishop Museum Press. Gladwin, T. (1970). East is a big bird: Navigation and logic on Puluwat Atoll. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Haddon, A. C., & Hornell, J. (1975). Canoes of Oceania. Honolulu, HI: Bishop Museum Press.

- Irwin, G. (1992). The prehistoric exploration and colonisation of the Pacific. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lewis, D. (1972). We, the navigators. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.