Monasticism, from the Greek root meaning “alone” (mono) and from the Latin monachus (monk), refers to an institutionalized religious form of life that is characterized by radical solitude and mortification. Although most often associated with great religious traditions of Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism, elements of monasticism are also evident in other traditions. The basis of the phenomenon is captured in a Native American elder’s words: “True wisdom is only found far away from people, out in great solitude, and it is not found in play, but only through suffering. Suffering and solitude open the human mind, and therefore [one] must seek wisdom alone.”

The worldview of monasticism is the ideals of truth and purity. From this perspective, the ordinary world prevents individuals from reaching their spiritual potential, so that a separation is needed. Most commonly, the elements essential to this quest for spiritual perfection are (a) celibacy (i.e., the freedom from familial or physical impairments), (b) poverty (i.e., the relinquishment of comforts of the world), and (c) obedience to some other person, usually a teacher, leading to the surrender of one’s own will. These facets of monasticism have fascinated anthropologists for some time, leading to a number of sociocultural interpretations for the motivation and functions of these institutions. For example, Robert Levy, Gananath Obeyeskere, and others have used their work in psychological analysis to explain motivations and cultural structures that underpin the monastic vocation in various cultures.

Monasticism is commonly divided into two types: cenobitic and eremitic. The cenobitic life is characterized by a communal form of existence and is the most common type. The eremetic life is characterized by the life of the hermits, who tend to live in solitude and rarely are in contact with other humans. Most monastic traditions have elements of both. However, the Christian tradition of the Desert Fathers, the contemporary Carthusians, and the Jain ascetics are most often cited as eremitic groups.

Institutionalized monastic traditions are found in Jainism, Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Monasticism was also an element in the Vestal Virgins of Rome, the Peruvian Virgins of the Sun, and the Therapeutae of Egypt. The development of monastic systems runs parallel to the development of state systems in world history and to the organization of full-time religious specialists and the concern with secularization of society. Each of the monastic traditions depends on a philosophy of dualism in which the world is viewed as corrupt, a burden, or evil. The element of the human that sets one apart from nature is commonly referred to as the soul. In the monastic philosophy, then, the soul must be purified from matter. The universal process of this dualistic opposition is one of bodily mortification and contemplation and study on spiritual things.

Hindu Tradition

The Hindu tradition of monasticism is often viewed as the oldest form of monasticism. The Sramanas (Sanskrit: “recluse”) gathered circa 1500 BC to study the Vedic and practiced bodily mortifications. Also present in Proto-Dravidian and Pre-Aryan areas, these groups developed eremitic styles as well. By 600 to 200 BC, the ashram was an institution primarily for eremitic sects in India.

With the rise of Jainism, the ashrams became organized monastic centers. Jainism, which is noted for its attention to self-denial and mortification, has been especially important in the Hindu monastic tradition. The early organizer, Mahavira, originally established centers of professed monks and nuns who were ministered to by the local laity. An important development was the rejection of the caste system by the Jains and the later general disinclination to allow nuns (especially among the Digamboras). The ascetic life of the Jain monk is that of a wanderer whose five vows are those of nonviolence, truthfulness, nonstealing, chastity (i.e., no dealings with gods, humans, or animals of the opposite sex), and being indifferent to all things experienced through the senses. There has never been a well-organized system of monasticism in Hindu outside of the empire of Baktashiyah in Turkey. Each ashram is independent of the others, allowing a monk/nun to enter and leave relatively easily from any ashram.

With the rise of Jainism, the ashrams became organized monastic centers. Jainism, which is noted for its attention to self-denial and mortification, has been especially important in the Hindu monastic tradition. The early organizer, Mahavira, originally established centers of professed monks and nuns who were ministered to by the local laity. An important development was the rejection of the caste system by the Jains and the later general disinclination to allow nuns (especially among the Digamboras). The ascetic life of the Jain monk is that of a wanderer whose five vows are those of nonviolence, truthfulness, nonstealing, chastity (i.e., no dealings with gods, humans, or animals of the opposite sex), and being indifferent to all things experienced through the senses. There has never been a well-organized system of monasticism in Hindu outside of the empire of Baktashiyah in Turkey. Each ashram is independent of the others, allowing a monk/nun to enter and leave relatively easily from any ashram.

Buddhist Tradition

The development of Buddhist monasticism is directly related to the Gautama Buddha (ca. 560-480 BC). According to the Buddha, the perfection of the Hindu way could be attained only through withdrawal from the world. Only those who dedicated themselves to the religious life could attain perfection or Nirvana. As with Jainism, Buddha chose to ignore caste differences and initially opposed the inclusion of nuns in the monastic endeavor. The original Sanga, or organization, was based on relative moderation of discipline and mortification and on a close relationship with the laity. The contemporary Theravada tradition of Southeast Asia is often viewed as an example of this form of monasticism.

Buddhism is a way of life that is essentially monastic in its ideal form. One can attain the perfection of life only by denying the reality of the world and seeking release in meditation. To strip dependency on the self, monks typically will beg for alms and food and will strive to develop the desired characteristics of humility and tranquility. Again, because Buddhist monasteries are also independent of one another, the rule of the individual abbot varies from place to place. There is relative ease of movement for the monks from one monastery to another or back to the laity.

The levels of importance and dominance of Buddhism among the cultures of Southeast Asia are diverse. Buddhism has dominated life in some countries, such as Burma and Thailand, and in many countries all men are expected to spend some time in monastic enclosures. Buddhist monasticism probably reached a height of influence in Tibet, where monks composed more than a fifth of the population and the Dali Lama ruled the country for more than three centuries. In Ceylon, the local abbot also often served as the local secular judge. Some thousand years after the death of the Buddha, the Zen form of Chinese Japanese Buddhism became a defining revitalization movement in parts of Southeast Asia. Zen Buddhism, allegedly, a truer form of the Buddha’s intention for the attainment of perfection, is characterized by rigorous disciplines of contemplation and scholarly pursuits.

Christian Traditions

Monasticism in the Western and Eastern Christian traditions is characterized by a great deal of organization. Although it has never been as dominant as a way of life as has Buddhist monasticism, it has played a very important role in cultural continuity and adaptations. Usually, it is traced to the antisecular movements of the 3rd century AD and to St. Anthony in Egypt, whose form featured the desert anchorites. The Eastern tradition of monastic enclosure is attributed to St. Basil of Caesarea (379 AD) and his sister, St. Macrina the Younger, whereas the Western tradition is attributed to St. Benedict of Nursia (ca. 500). Each of these initial movements was based on a neo-Platonic philosophy of dualism and the withdrawal from the world to contemplate and attain holiness. Also noteworthy here is the fairly radical cultural relative equality of women in the monastic movements.

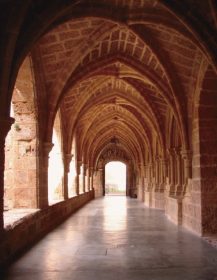

The spread of monasticism in the Byzantine Empire was rapid, following the establishment of Christianity. It was well established in the East by the 7th century AD and as far as Moscow by the 14th century. To the West, monastic communities were well in place by the 4th century AD in Gaul and by the 5th century in Ireland, Carthage, and Italy. By the early Middle Ages, monasticism had become a defining and powerful economic, political, and religious entity in Europe, with many monasteries controlling land, labor, and commerce.

One of the most significant factors that separate Western monasticism from other monastic forms is the Rule of St. Benedict. Whereas St. Bruno established the Catholic eremitic tradition at Chartres, France (Carthusians), Benedict’s monastic community at Monte Cassino, Italy, during the 5th and 6th centuries AD became the role model for highly organized and detailed ways of living that became a way of uniting most of the European monasteries. Individuals living according to this tradition vow perpetual chastity, poverty, and obedience to their abbot and also vow stability to the particular monastery. So, rather than the transitional monasticism of the other great traditions, monks of the Western church became institutionalized professionals and often were elevated to high offices within the Roman Catholic Church. The monks of the West labored in fields, illuminated manuscripts, and devoted themselves to lives of silence, prayer, and study. It was through this diligent regime that the first Western universities came about during the 13th century.

Unlike Buddhist traditions, the Christian traditions became quite popular and welcoming to women. The abbesses of these communities could often attain a great deal of power and prestige. The relative autonomy and access to some venues of learning provided many women with an alternative to their limited options as females in many European countries.

The power centralized in the large monastic communities often led to accumulation of great wealth and prestige. During the 14th and 15th centuries AD, St. Francis of Assisi and St. Dominic led monastic reform movements that attempted to renew poverty as a defining element of the monastic/communal life. Thus, the order of friars, or monks who are also involved with worldly daily life but who live a mendicant lifestyle, was formed. However, the Protestant reformation of the 15th and 16th centuries eradicated monasticism from Protestant areas. They were not reestablished into Protestantism until the Oxford movement of the 19th century in England and after World War II in Taize, France.

Judaic and Islamic Traditions

Judaism and Islam have some elements of monasticism, but they have a much less dominant impact on their history. Withdrawal from the world is not necessary to find salvation for either religion. In fact, an active engagement with the world is often viewed as a virtue. Muhammad stated that “there are no monks in Islam,” and except for some Sufi sects, the Sensui of Sudan, and the Sahara, this remains the case today. Similarly, Judaism has had some elements of monasticism during periods of stress and upheaval (e.g., the Essene community) but has never promulgated a separation of the person from the community.

Monasticism continues to be an important institution in the Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu cultures. The West experienced a resurgence of monastic vocations after World War II, and many monks had a vital role during the Vatican II reforms of the 1960s. Buddhist monasticism experienced a revival during the latter part of the 20th century as well, with a great deal of interest spurred by the persecution of monks in Tibet, China, and elsewhere. And although India has witnessed a great deal of industrialized development, the ascetic path remains an important socio-cultural institution for the many Hindus. In the area of anthropology, current scholarship includes psychological studies of monastic methods and motivations, the form and function of monasticism in defining culture stability and change, and the role of monasticism in religious consciousness.

References:

- Berman, C. H. (2000). The Cistercian evolution: The invention of a religious order in twelfth-century Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Gilchrist, R. (1994). Gender and material culture: The archaeology of religious women. New York: Routledge.

- Goehring, J. E. (1999). Ascetics, society, and the desert: Studies in Egyptian monasticism. Harrisburg, PA:

- Trinity Press International.

- Johnston, W. (Ed.). (2000). Encyclopedia of monasticism. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- Mills, M. A. (2003). Identity, ritual, and state in Tibetan Buddhism: The foundations of authority in Gelukpa monasticism. New York: Routledge-Curzon, Simons, W. (2001). Cities of ladies: Beguine communities in the medieval low countries, 1200-1565. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Suzuki, D. T. (1964). An introduction to Zen Buddhism (with a foreword by C. G. Jung). New York: Grove.

- (1985). A history of the monks of Syria by Theodoret of Cyrrhus (with an introduction and notes by R. M. Price, Trans.). Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications.

- Viker, K. S. (2000). Sufi brotherhoods in Africa. In N. Levtzion (Ed.), History of Islam in Africa (pp. 441-476). Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Wu Yin, B. (2001). Choosing simplicity: A commentary on the Bhikshuni Pratimoksha by venerable Bhikshuni Wu Yin (B. J. Shih, Trans., B. T. Chodron, Ed.). Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications.