Migrations are a constant in human history. Indeed, it is a mistake to treat residential stability as normal and thus not needing explanation while treating migration as abnormal, novel, and thus uniquely needing explanation. Unfortunately, this has not been the way in which the social sciences (including anthropology) have developed, and this entry focuses on migration with only brief mentions of the distinctive, and sometimes unusual, conditions favoring stationary or repetitively circulatory cultures.

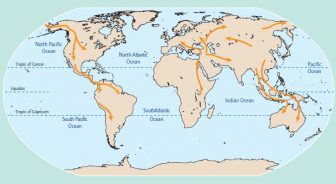

Although it is debated whether Homo sapiens sapiens emerged in Africa alone or via a trellis work of interacting places across the Old World, migration certainly accounts for the remarkable spread of humanity across the world. To take three dramatic examples, pioneers on simple boats reached Australia no later than 40,000 years ago, the New World was populated (probably on foot across land bridges) no later than 13,000 years ago, and remote Pacific islands have been settled over the past 3,600 years by sophisticated navigators using outrigger canoes. Nor were these pioneering movements into unsettled areas the only instances of migration in the human past. Many waves of migration and cultural change (it is hard to separate these) have shaped the map of world culture regions. A characteristic example is the Bantu expansion, associated with tropical root crops, iron working, and cattle, spreading south and east across sub-Saharan Africa.

Mobility in small-scale societies takes place through group fissioning after disputes (often when existing groups grow in size and have become crowded) and through cross-spatial marriage and gift exchange networks. Such movements can become migrations (a directional flow) for varied reasons, including environmental changes and innovations in social organization and food production. We see the results of such flows as a “diffusion wave” across a large spatial scale. In the past, simplistic and often speculative models envisioned migrations as vast and dramatic movements of conquerors or adventurers. Today, we piece together more complex and gradual changes from three sources of evidence: genetic branching, historically related languages, and the archaeological record. It is often unclear whether a diffusion wave represented the migration of new people, the conversion to new cultural practices and social organizations, or both.

As societies became larger in scale, politically centralized, and more unequal, new patterns of migration emerged. Violent political expansion and consolidation—warfare and repression of subject peoples, especially religious and political dissenters— became a cause of migrations, continuing to the present day. Centralized states deliberately relocated populations and encouraged colonizers, often to consolidate frontiers and sometimes to encourage the production of desired crops. Meanwhile, wealthy peoples and themselves settled down and changed culturally. As a result of these various processes, diasporas formed important commercial, artisanal, and religious networks.

An important phenomenon, labor migration by peasants, links the world of premodern complex societies with the modern migratory world. Situations in which landlords freeze peasants into place through rigid labor duties are important but have never been universal and have broken down thoroughly as capitalism has expanded. Peasants often have too many children to inherit access to land, and those extra sons and daughters then migrate. In some cases, they open up new land, but this option is limited, so that they often become labor migrants in cities and expanding commercial agricultural frontiers. The capitalist world system stimulates migration through the modernization of agriculture in sending areas, the displacement of peasants from previously intensive labor systems, the impact on hand artisans by industry, and the collapse of putting-out production systems. On the other end, employers actively recruit new workers to undercut existing workers or during periods of expanding production. Hence, it is dynamic social change, rather than stagnation and poverty, that causes people to leave their accustomed homes.

An important phenomenon, labor migration by peasants, links the world of premodern complex societies with the modern migratory world. Situations in which landlords freeze peasants into place through rigid labor duties are important but have never been universal and have broken down thoroughly as capitalism has expanded. Peasants often have too many children to inherit access to land, and those extra sons and daughters then migrate. In some cases, they open up new land, but this option is limited, so that they often become labor migrants in cities and expanding commercial agricultural frontiers. The capitalist world system stimulates migration through the modernization of agriculture in sending areas, the displacement of peasants from previously intensive labor systems, the impact on hand artisans by industry, and the collapse of putting-out production systems. On the other end, employers actively recruit new workers to undercut existing workers or during periods of expanding production. Hence, it is dynamic social change, rather than stagnation and poverty, that causes people to leave their accustomed homes.

The capitalist world system has seen four major kinds of migration: commodity slavery (especially the African slave trade to plantation regions of the New World), displaced peasants from Asia and Europe to the Americas and within these regions, migrations of specialized businesspeople and skilled workers, and refugees from persecution. Even the latter become labor migrants as they find ways of surviving in new economies. Migration includes both internal movement and international movement, which tend to be conceptualized and studied as if they are different but in fact have similar social dynamics except in terms of political status as a national or nonnational matter. For example, internal migration studies often focus on the topic of urbanization of rural people, but this is an important feature of international migration as well.

The nation-state does matter, in particular the status of “citizen.” Citizenship, which began in city-states, constitutes an equal collective access to various rights and institutions in exchange for loyalty to the central national executive (e.g., paying taxes, doing military service). But as citizenship collects together insiders, it also excludes outsiders, such as migrants, or creates ambivalent transitional categories for them. Hence, for anthropologists to understand the migrant experience, it is also necessary to understand the specific cultural construction of the insider/outsider divide.

Cultural anthropologists, with their predilection for studying the powerless and culturally distinctive, have provided a large number of ethnographies of migrants, many of which are of excellent quality. They have shown that migration does not necessarily lead to social disorganization and have emphasized the importance of networks for migrants. Anthropologists have explored the concept of transnationalism, in which mobile communities of people have social, cultural, and political presence in more than one nation at a given time. They also have looked at the nuances of social, cultural, and political incorporation into new societies. And recently, critical anthropologists have turned their fine-grained ethnographic focus to the articulations between migrants and dominant populations, including the division of labor and business markets into migrant and nonmigrant segments, the mechanisms of exploitation of the surplus produced through that segmentation, and the borders and other devices of legal classification and enforcement that migrants encounter in their journeys across nation-states.

References:

- Brettell, C. B., & Hollifield, J. (Eds.). (2000). Migration theory: Talking across disciplines. London: Routledge.

- Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., & Cavalli-Sforza, F. (1995). The great human diasporas: The history of diversity and evolution. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Foner, N. (Ed.). (2003). American arrivals: Anthropology engages the new immigration. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.