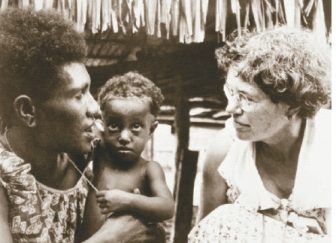

Margaret Mead, the most prominent and recognized anthropologist of the 20th century, had a profound influence on anthropology and feminism. She achieved celebrity status and became an American oracle.

Mead was born into a Quaker family in Philadelphia on December 16, 1901, the daughter of Edward Sherwood Mead (a professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School) and Emily Fogg Mead (a sociologist and suffragist). Margaret had lived in 60 houses by 6 years of age. She attended DePauw University (1919-1920), graduated with a B.A. degree from Barnard College (1923), and received her M.A. in psychology from Columbia University (1924) and her Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University (1929) studying under Franz Boas and being mentored by Ruth Benedict.

While establishing her home base in New York City, Mead was appointed curator of ethnology at the American Museum of Natural History (1926), associate curator (1942), curator (1964), and curator emeritus (1969). She was appointed adjunct professor of anthropology at Columbia (1954-1978), professor of anthropology while she founded the department at Fordham University (1968), visiting lecturer in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati School of Medicine (1957-1958), and visiting lecturer at the Menninger Foundation in Topeka, Kansas (1959).

Diminutive in stature yet strong in character and stamina, Mead was never known to shrink from controversy. She wielded proclamations of her field research findings in anthropology, her feminist opinions on the role of women, and her recommendations regarding sexual liberation, marriage, and marijuana decriminalization. She carried a big stick—a forked walking stick—and spoke other than softly (an interesting contrast to Boas’s nemesis, President Theodore Roosevelt). She seemed larger than life. Only Benedict knew her well. They became intimate friends in their roles as mentor and student, and Mead became the child Benedict never had. She became absorbed in Benedict’s work and internalized the theory of cultural relativity.

Mead’s findings in her field studies were provocative. Having obtained a National Research Council fellowship (1925) while on staff at the Museum in Honolulu, she traveled to the island of Tau in Samoa to verify Boas’s hypothesis that culture and not biology influences adolescent behavior the most. The product of this research, Coming of Age in Samoa (1928), caused a public stir due to her descriptions of unrepressed adolescent Samoan girls’ sexual activity compared with that of American girls as well as her recommendation that Americans could learn how to raise children from Samoans. The stir was heightened when some colleagues claimed that Mead ignored biological factors in her emphasis on the theory of cultural determinism. At the time, she was married to but separated from Luther Cressman, and she then met and married Reo Fortune (1928), with whom she traveled to Manus and the village of Peri in the Great Admiralty archipelago.

Mead’s work in Peri led to Growing Up in New Guinea (1930), in which she argued that the difference between the “civilized mind” and the “primitive mind” had been exaggerated; human nature was malleable. The work was highly received and inspired her to study the Omaha Indians of Nebraska (1930), followed by research in Alitoa, New Guinea (1931). There, Mead developed a typology of aggression based on the pacifist Arapesh mountain people and the violent Mundugamour village people, and she also studied the Tchambuli people while living with the Washkuk tribe. Her typology was a major contribution to the theory of cultural relativity.

Following a divorce from Fortune, Mead married ethnologist Gregory Bateson (1936). They conducted 2 years of field-work in Bali, where they used photography in research and annotated more than 25,000 photographs, many taken of the Balinese ritual of trances, a fundamental element in Balinese culture (“Trance and Dance in Bali” in Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis, 1942).

In 1944, Mead and Benedict collaborated to form the Institute for International Studies to analyze contemporary societies from which salient elements could be incorporated into a new world order.

In 1944, Mead and Benedict collaborated to form the Institute for International Studies to analyze contemporary societies from which salient elements could be incorporated into a new world order.

Mead’s prolific writings include And Keep Your Powder Dry: An Anthropologist Looks at America (1942); Male and Female: A Study of the Sexes in the Changing World (1949); New Lives for Old (1956); Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap (1970); and her autobiographical Blackberry Winter: My Early Years (1972). Feminism is a recur-rent theme throughout her writings. She had a demonstrable sense of adventure and heroism along with a disdain for the passive cultural role of women in the United States. Her focus on women’s gender roles in cultures and child rearing spotlighted her as an influential leader of feminism and women’s liberation while she defended women’s right to develop their talents in humanities and intuition. She became one of the most recognized leaders of the women’s movement of the 1960s. Whereas her mentor Benedict was introspective and a role model of feminism through her work, Mead was an extrovert who exhorted women’s liberation. She gave more than 100 speeches every year, wrote for Redbook magazine, and was unswerving about her opinions.

Of particular interest is Mead’s experience with her daughter and only child Mary Catherine, who was born in 1939. Mead insisted on natural childbirth, which she had observed in her field research, and she wanted the birth to be filmed and recorded. She enlisted the cooperation of pediatrician Benjamin Spock, and the event gained national attention. Mary Catherine Bateson Kassarjian became an anthropologist and dean of social sciences at Raza Shah Civar University in Iran.

Mead received many kudos, including election to president of seven professional organizations, for example, the World Federation of Mental Health (1956-1957), the American Anthropological Association (1960), and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (1975). She received UNESCO’s Kalinga Prize. She died of pancreatic cancer on November 15, 1978. Time Magazine’s obituary of Mead was titled “Grandmother to the Global Village.”

References:

- Bateson, M. C. (1984). With a daughter’s eye: A memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. New York: William Morrow.

- Howard, J. (1984). Margaret Mead: A life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Lapsley, H. (1999). Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict: The kinship of women. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Mead, M., & Metraux, R. B. (1980). Aspects of the present. New York: William Morrow.

- Rice, E. (1979). Margaret Mead: A portrait. New York: Harper & Row.