Lucy is among the most famous fossil skeletons believed to represent an early stage of hominid evolution following separation of the human lineage from its nearest living ape relative. At 3.2 million years, Lucy was the oldest and most complete hominid skeleton that clearly showed evidence of bipedal locomotion. The label “Lucy” provided a personal metaphor for an individual believed to be a female approximately 20 years of age at the time of her death. Classified as Australopithecus afarensis, Lucy was one of nine species clustered under the genus Australopithecus despite a poor understanding of their evolutionary relationships and status.

Numerous portraits of the australopiths have combined the constraints of fossil morphology with the addition of soft tissue features that are imagined to be present based on the presumption that Lucy and other early hominids resembled those apes most closely related to humans. Because those apes are widely believed to be chimpanzees, based on the similarity of DNA base sequences between chimpanzees and humans, the soft tissues assigned to Lucy are those of chimpanzees. Lucy and other early hominids are given the fleshy nostrils unique to chimpanzees and gorillas among the living primates. The body hair is short and dark and projects away from the face as with chimpanzees, and there are no beard and mustache present in males because it is not found in chimpanzees. Instead, sparse hair is shown on the underside of the lower jaw, whereas the forehead is imagined to be free of hair as with humans but unlike chimpanzees.

Although the soft tissues may be a matter of conjecture, the hard tissues offer some constraints that are problematic for any chimpanzee reconstruction for Lucy and other australopiths. The forward-projecting brow ridge extending across and between the eyes that gives chimpanzees and gorillas that classic hooded appearance is missing. Instead, the ridges of Lucy and other australopiths are limited to the region immediately above the eye. Neither do the eyebrow ridges project forward in the manner of chimpanzees and gorillas. Also absent is the channel or sulcus that lies immediately behind the brow ridges in chimpanzees and gorillas. In addition to the absence of these African ape features is the presence of a different kind of cheekbone. The cheekbone of the chimpanzee is narrow and slopes back along the lower margin. The complete opposite is found in australopiths, where the cheekbone is very broad and is vertical or slopes forward at the lower margin.

The combination of these three features is hardly congruent with what might be expected of a chimpanzee ancestry for humans. When artists add chimpanzee features in their reconstructions of australopiths, the result is a very incongruous bipedal “chimpanzee” that has massively broad cheekbones and lacks the classic supraorbital ridge (torus) and posttoral depression of African apes. Perhaps their absence may be attributed to an evolutionary loss of the features since separation from the common ancestor with chimpanzees, whereas the cheekbones are just a novel development that was then later lost in the evolution of Homo. This ad hoc scenario may be all well and good, but there is another great ape that shows no such contradictions in skull structure.

Comparisons between australopiths and orangutans demonstrate no such obvious contradictions of skull morphology. Orangutans have broad cheekbones with forwardly oriented lower margins as with Lucy and other australopiths. Orangutans also have eyebrow ridges that do not project up in the African ape manner. These similarities may be passed off as a phylogenetically meaningless coincidence, but there are at least 42 known features uniquely shared between orangutans and humans—far more than any uniquely shared features between humans and chimpanzees. The skull of the australopiths also shows several skeletal features that are otherwise characteristic of orangutans or recognized orangutan relatives, including upper palate thickness, nasal bone thickness, and cheekbone development.

Lateral view of Australopithecus africanus specimen Sts 71 from Sterkfontein. This view illustrates the lower surface of a flattened orbital plane and anterior orientation of the zygomatic roots.

Lateral view of Australopithecus africanus specimen Sts 71 from Sterkfontein. This view illustrates the lower surface of a flattened orbital plane and anterior orientation of the zygomatic roots.

The orangutan resemblance of australopith Sts 71 is further emphasized by a more forwardly projecting upper jaw and a more marked disparity in size and shape between the upper central and lateral incisors. Although the skull of Lucy is represented by only a few fragments, these are shown in reconstructions to be part of a skull that has an overall similarity to that of the chimpanzee with a relatively low domed cranium on the assumption that the early hominids would show chimpanzee-like skeletal features. This assumption was recently found to be wanting in a reconstruction of A. afarensis using a more complete skull for this species. By carefully connecting the skull fragments of the fossil AL 444-2, William Kimbel and colleagues recently developed a most un-chimpanzeelike reconstruction. In addition to the orangutan-like brows and cheekbones, the infraorbital region of the lower region of the face is flat and vertical rather than concave as with chimpanzees. Even the upper jaw shows a slight upward inclination, and the cranial area rises in a gradual dome as with orangutans.

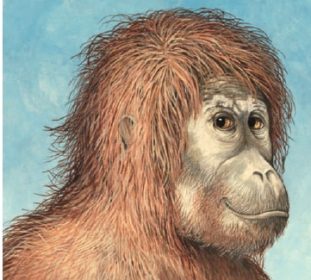

Collectively, the structural features of Lucy and other australopiths give an appearance that is more like orangutans than chimpanzees. When these features are combined with soft tissue features that would be expected of an African orangutan relative, a completely new interpretative portrait becomes possible. This potential was recently explored by the scientific illustrator Bill Parsons at the Buffalo Museum of Science. The result shows a new kind of “Lucy” with the flat, vertical infraorbital region and high cheekbones indicated by skull morphology. In addition, the hair is now forwardly oriented, the forehead is exposed, the nostrils lack the fleshy extensions found in African apes, and Lucy can smile without showing teeth. All of these features are uniquely shared by humans and orangutans, and if these and other unique features indicate a common ancestry, then they can be fully expected to have occurred in early hominids such as Lucy.

The new portrait of Lucy is now on display at the Buffalo Museum of Science in the world’s first exhibition showing the contrasting chimpanzee and orangutan reconstructions of early hominids. The purpose of this display is to show that it is possible to derive different results by emphasizing different elements of the same information. The orangutan connection with humans is generally ignored in favor of the chimpanzee connection principally through the widely accepted view that genetic base pair sequence similarities between humans and chimpanzees are the final and only proof of hominid evolutionary relationships. The trouble with this proposition is the fact that australopiths do not look like chimpanzees. Instead, the clearly orangutan features of Lucy and her relatives suggest something quite different—different enough to make one smile just like an orangutan.

The new portrait of Lucy is now on display at the Buffalo Museum of Science in the world’s first exhibition showing the contrasting chimpanzee and orangutan reconstructions of early hominids. The purpose of this display is to show that it is possible to derive different results by emphasizing different elements of the same information. The orangutan connection with humans is generally ignored in favor of the chimpanzee connection principally through the widely accepted view that genetic base pair sequence similarities between humans and chimpanzees are the final and only proof of hominid evolutionary relationships. The trouble with this proposition is the fact that australopiths do not look like chimpanzees. Instead, the clearly orangutan features of Lucy and her relatives suggest something quite different—different enough to make one smile just like an orangutan.

Bust of Lucy interpreted from a recently reconstructed skull of Australopithecus afarensis supporting a cranial profile with a flattened and vertically inclined orbital region, broad cheekbones, and absence of the African ape supraorbital torus. This illustration, by the scientific illustrator William Parsons, is currently on display at the Buffalo Museum of Science.

References:

- Kimbel, W. H., Rak, Y., & Johanson, D. C. (2004). The skull of Australopithecus afarensis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Schwartz, J. H. (2004). The red ape (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

- Schwartz, J. H., & Tattersall, I. (2005). The human fossil record, Vol. 3: Craniodental morphology of Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Orrorin. New York: Wiley-Liss.

- Tattersall, I., & Schwartz, J. H. (2000). Extinct humans. Boulder, CO: Westview.