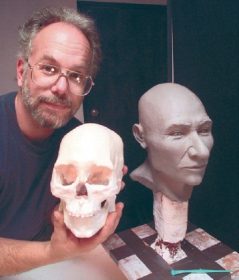

On July 28, 1996, the random discovery of a skull on the banks of the Columbia River near Kennewick, Washington changed the climate of archaeology. Discovered by two teenagers and initially examined by James Chatters, forensic anthropologist, this skull had many characteristics indicating its Caucasian origin. Characteristics of the skull’s teeth, however, suggested an extremely old specimen (around 5,000 years). Finding bones with Caucasian characteristics is not an unusual occurrence; however, potential dating of the bones to precontact times is certainly uncommon in North America. This incongruity became more pronounced after the recovery and examination of the remaining skeletal elements.

The analysis of the almost-complete skeleton suggested that the bones belonged to a 40- to 50-year-old male with Caucasoid features who was approximately 5 feet, 9 inches tall and had sustained injuries throughout his life. In his right pelvis was embedded a projectile point resembling those manufactured and used by the people who inhabited the Columbia Plateau between 4,500 and 9,000 years ago. This puzzle became increasing difficult for Chatters to solve; as a result, he decided to send a small piece of bone for radiocarbon dating in order to get a better sense of the age of the skeleton. The results of the radiocarbon dating came as a shock, making “Kennewick Man” one of the oldest skeletons in North America and beginning a seemingly never-ending battle over the specimen.

Because Kennewick Man was discovered on a portion of the Columbia River that is federal land maintained by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) came into play. NAGPRA was signed into law in 1990; it essentially states that if human remains are found on federal lands and their cultural affiliation can be established, those remains and associated grave goods must be returned to the affiliated tribe. The same portion of the Columbia River is also considered to be part of traditional homeland by the Umatilla tribe, as well as several other tribes in the area. As a result, by September of 1996, five tribes (Umatilla, Yakama, Nez Perce, Colville, and Wanapum) had jointly made a formal claim to the Kennewick Man skeletal remains. At this point, scientific study of the skeleton was halted. The Army Corps of Engineers took possession of the skeleton and announced intended repatriation of the bones to the alliance of tribes.

In October of 1996, eight well-known scientists sued to gain access to the Kennewick Man remains. Citing civil rights violations, a lack of due process, and the lack of definitive affiliation with any single Native American tribe (especially given the presence of several traits more consistent with Europeans), these scientists argued the necessity of studying the skeleton in order to determine ancestry and to allow the entire American public access to knowledge about its past. For the Native American tribes, Kennewick Man represented an ancestor, whose bones are sacred and who deserved reburial; for archaeologists, the skeleton represented a piece of potentially significant information in ongoing research on the peopling of the North American continent.

Several theories exist regarding the peopling of the New World. Evidence places humans in the New World 12,000 years ago. One popular theory posits humans coming across the Bering Strait into Alaska and journeying south through an ice-free corridor into the Plains area of North America. Recently, sites and artifacts dating to earlier than 12,000 years have been discovered in eastern North America and in South America. This new evidence suggests the possibility of several different migrations of humans into the New World, potentially from parts of the world other than northern Asia and possibly earlier than researchers have previously assumed. Skeletal remains from these very early periods are rare; the completeness and ancient date of the skeleton make Kennewick Man a potentially important clue to increasing our knowledge about the earlier inhabitants of the North American continent.

For almost eight years, the battle continued over Kennewick Man. Before any ruling was entertained, Justice John Jelderks, Justice Magistrate of the United States District Court in Portland, Oregon, ordered the study of the skeleton to determine cultural affiliation. In October of 1999, the cultural affiliation report indicated that Kennewick Man was not similar morphologically to modern Native Americans or as close to European Americans as was initially presumed; rather, Kennewick Man most closely resembled populations from southern Asia, specifically, groups of Polynesia and the Ainu of Japan.

For almost eight years, the battle continued over Kennewick Man. Before any ruling was entertained, Justice John Jelderks, Justice Magistrate of the United States District Court in Portland, Oregon, ordered the study of the skeleton to determine cultural affiliation. In October of 1999, the cultural affiliation report indicated that Kennewick Man was not similar morphologically to modern Native Americans or as close to European Americans as was initially presumed; rather, Kennewick Man most closely resembled populations from southern Asia, specifically, groups of Polynesia and the Ainu of Japan.

Multiple reports assessing cultural affiliation, coupled with extensive testimony, led to a ruling in August, 2002, stating that scientists should be allowed access to the skeletal remains, and that the remains were not to be repatriated. Jelderks argued that in order for present-day tribes to claim skeletal remains or associated funerary objects, they must be able to establish a direct relationship with the skeletal remains. Jelderks argued that no such relationship was established for Kennewick Man and the tribes requesting repatriation of the remains. By the end of October, 2002, the tribes and the federal government had appealed the ruling of Justice Jelderks and, in the early part of the following year, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the study of the skeletal remains pending their final decision.

In 2004, the battle seemingly came to an end when the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision made by Judge Jelderks in 2002. The ruling noted that a relationship between Kennewick Man and the tribes involved in the case was not adequately established. The ruling further indicated that the language of NAGPRA requires human skeletal remains to bear a relationship to a present-day tribe or culture; it also emphasized that the purpose of NAGPRA would not be served if the law ensured repatriation of remains to Native American groups without an established relationship to those remains. A proposed rehearing was rejected and the federal government declined to appeal the decision further.

While the Kennewick Man case appears to have been closed, it unearthed several deep-rooted issues. In Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity, David Thomas explains, “The multicultural tug-of-war over Kennewick Man raises deep questions about how we can make the past serve the diverse purposes of the present, Indians as well as white. It also challenges us to define when ancient bones stop being tribal and simply become human.”

References:

- Benedict, J. (2003). No bone unturned: The adventures of a top Smithsonian forensic scientist and the legal battle for America’s oldest skeletons. New York: HarperCollins.

- Chatters, J. C. (2000). The recovery and first analysis of an early Holocene human skeleton from Kennewick, Washington. American Antiquity, 65, 291-316.

- Chatters, J. C. (2001). Ancient encounters: Kennewick Man and the first Americans. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Downey, R. (2000). The riddle of the bones: Politics, science, and the story of Kennewick Man. New York: Copernicus.

- McManamon, F. P. (2004). Kennewick Man. Retrieved aad/kennewick/

- Thomas, D. H. (2000). Skull wars: Kennewick Man, archaeology, and the battle for Native American identity. New York: Basic Books.