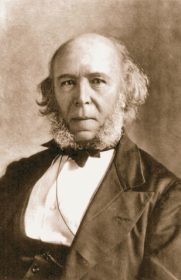

Herbert Spencer, a British social philosopher and sociologist, was a widely recognized visionary and the founder of the theory of sociocultural evolution, and he had a major influence on Charles Darwin and his theory of biological evolution.

Born in Derby, England in 1820, Spencer trained as a civil engineer and then became interested in social and economic issues, joining The Economist as a subeditor (1848) and writing Social Statics (1851), a book in which he described the synergy of society based on a core principle of justice—the law of equal freedom—which became the foundation of classic liberalism and the quintessential theory of the state.

Social Statics served as the dawn of Spencer’s theory of sociocultural evolution, which he developed as a hypothesis in “The Development Hypotheses” (1852), asserting that each species arose through adaptive changes of previously existing species. In “Progress: Its Law and Cause” (1857), Spencer further developed his theory of evolution, claiming that progress occurred along an evolutionary divergent timeline from homogeneous or undifferentiated to heterogeneous or differentiated. He applied this theory to the disciplines of biology, ethics, metaphysics, psychology and sociology, defining evolution as “a change from a state of relatively indefinite, incoherent, homogeneity to a state of relatively definite, coherent, heterogeneity.”

Spencer’s interest in organic evolution as well as general evolution led him to write that “life . . . has arisen by a progressive, unbroken evolution . . . through the immediate instrumentality of what we call natural causes.” He applied his approach to a comparative scientific study of society based on evolutionary principles, an approach distinct from that of the French sociologist Auguste Comte. Spencer’s approach required classification of all available ethnographic and historical data of human society and social behavior in order to derive generalizations.

Spencer visualized sociology as the focus of the study of the natural history of society, and he considered descriptive sociology to be the “only history that is of practical value” and comparative sociology to be a compilation of the lives of nations and the “subsequent determination of the ultimate laws to which social phenomena conform.”

Spencer maintained that there were many parallels between biological organisms and human societies, and he often referred to society as an organic system of structures that are mutually dependent. To Spencer, social functions create social structures, and to this position he assigned the general law of organization that “difference of functions entails differentiation and division of the parts performing them.”

Spencer’s Principles of Sociology stands as a significant contribution to the theory and understanding of evolution. His theory that humanity evolves from a relative, socially static, undifferentiated society to a utilitarian, socially dynamic, differentiated society where social structures and functions transform to meet needs is an organismic model of interrelated and interdependent structures and functions (from the inorganic to the superorganic) as social systems where consequences occur as “the survival of the fittest.” His functionalist theory of evolution became known as Social Darwinism.

Spencer’s Principles of Sociology stands as a significant contribution to the theory and understanding of evolution. His theory that humanity evolves from a relative, socially static, undifferentiated society to a utilitarian, socially dynamic, differentiated society where social structures and functions transform to meet needs is an organismic model of interrelated and interdependent structures and functions (from the inorganic to the superorganic) as social systems where consequences occur as “the survival of the fittest.” His functionalist theory of evolution became known as Social Darwinism.

Spencer’s social systems theory of evolution (statics and dynamics) gained popular appeal in the late 1800s, and it contributed to the intellectual revolution of the 19th century, influencing the development of anthropology, biology, political science, psychology, and most important, sociology. His theory was formulated on the construction of a paradigm of ethnographic and historical data classified in a system of headings and subheadings. Spencer was the founder of systematic, inductive, comparative sociology which he called Descriptive and Comparative Sociology.

Spencer’s contributions to anthropology and sociology are profound and beyond measure. He was among the first to claim that human society can be studied scientifically, and he ranks with Edward B. Tylor and Lewis Henry Morgan as one of the three prominent sociocultural evolutionists of the 19th century. His rejection of special creation and acceptance of organic evolution with increased integration stirred the public and inflamed the religious. Spencer’s theory of sociocultural evolution together with Darwin’s theory of evolution through “natural selection” revolutionized intellectual thought and social mentality. To Spencer, human social behavior is based on a normative order that conforms to natural or ultimate law, which defines the principles of human social organizational forms including marriage and the family, property, and equal freedom.

The influence of Spencer’s works on modern social thought is omnipresent. Charles Horton Cooley, William Graham Sumner, William James, Emile Durkheim, Radcliffe-Brown, Thorstein Veblen, Simon Nelson Patten, and Edward L. Youmans were influenced by his works. His advocacy of individualism and laissez-faire based on the inheritance of acquired characteristics as imperatives of adaptation influenced 20th century capitalism, while his evolutionism brought strong reaction and rejection until the works of Leslie A. White, Julian H. Steward, and V. Gordon Childe helped anthropologists accept sociocultural evolution as a process of increasing structural differentiation and functional specialization.

References:

- Peel, J. D. Y. (1972). Herbert Spencer on social evolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Spencer, H. (1929). The principles of sociology (3 vols.). New York: Appleton.

- Spencer, H. (1966). The study of sociology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.