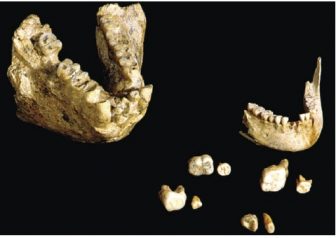

Gigantopithecus is the name given to an extinct ape discovered by G. H. R. von Koenigswald, in 1935. The two species, Gigantopithecus blacki (named after Koenigswald’s late friend and colleague Davidson Black) and G. giganteus (formerly bilaspurensis), are known primarily by teeth and jaws. The first tooth (as well as many of the more than 1,000 found after the original discovery) was discovered in a Hong Kong apothecary, where traditional Chinese pharmacists use fossils, referred to as “dragon bones,” in medicinal recipes.

As the name implies, these fossil apes were enormous. Based on the teeth and jaws, Gigantopithecus is estimated to have been 9 to 10 feet tall (3 m) and 600 to 1,200 lbs (270-550 kg). They were the largest primates known, more than twice the size of a mountain gorilla.

The great size of Gigantopithecus would have required it to spend most, if not all, of its time on the ground. Most scientists believe that Gigantopithecus was quadrupedal, walking on four legs. They may have walked on their knuckles, like a modern gorilla, or on their fists, like a modern orangutan. There are also some scientists who believe Gigantopithecus was bipedal, walking more like humans. Unfortunately, postcranial elements (such as pelvis or leg bones) have not been found. This makes accurately reconstructing its posture and locomotion difficult.

Because of its massive teeth and jaws, scientists originally believed that the diet of Gigantopithecus consisted of hard objects such as nuts and seeds. Later, analyses of residue left on the teeth led scientists to conclude that their diet probably consisted primarily of fibrous leaves. The fact that many of the Gigantopithecus fossils are found together with remains of ancient pandas suggests that they inhabited and exploited bamboo forests. Their predominantly leaf diet was most likely supplemented by fruit, based on the high rate (10%) of dental cavities found in G. blacki.

Fossils of G. giganteus are known from deposits in the Siwalik Hills of India. They have been dated to the Miocene approximately 6 to 7 million years ago. Fossils of G. blacki have been found in China and Vietnam and are much younger. Here, it appears that the species may have lived up to 500,000 years before becoming extinct.

Fossils of G. giganteus are known from deposits in the Siwalik Hills of India. They have been dated to the Miocene approximately 6 to 7 million years ago. Fossils of G. blacki have been found in China and Vietnam and are much younger. Here, it appears that the species may have lived up to 500,000 years before becoming extinct.

It is possible that the species became extinct when climatic changes caused large die-offs of the bamboo forests they inhabited. It is also possible that competition with giant pandas or early hominins, such as Homo erectus, may have caused their extinction. Since their discovery, Gigantopithecus has been interpreted variously as a human ancestor, as an overspecialized side branch of human evolution, or as an unusual fossil ape that had nothing to do with human evolution. Most scientists now recognize Gigantopithecus as an extinct ape that was more closely related to orangutans than to African apes or humans.

Some people have suggested that Bigfoot and/or Yeti (abominable snowman) are modern-day descendants of Gigantopithecus. However, there is no indisputable physical evidence to support this hypothesis. Scientists generally feel that if these modern-day creatures existed in numbers large enough to be a breeding population, they would leave physical remains and would have an observable effect on the environment.

References:

- Ciochon, R. L., Olsen J., & James, J. (1990). Other origins: The search for the giant ape in human prehistory. New York: Bantam Books.

- Ciochon, R. L., Piperno, D. R., & Thompson, R. G. (1990). Opal phytoliths found on the teeth of the extinct ape Gigantopithecus blacki: Implications for paleodietary studies. Proceedings ofthe National Academy of Sciences, 87, 8120-8124.

- Pettifor, E. (2000). From the teeth of the dragon: Gigantopithecus blacki. In M. Scully (Ed.), Selected readings in physical anthropology (pp. 143-149). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.