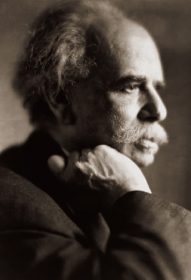

Franz Boas, considered the “father of American anthropology” and the architect of its contemporary structure, helped revolutionize the consciousness and conscience of humanity by fighting against 19th-century colonial Anglo-American ethnocentrism and racism and championing 20th-century cultural relativism, tolerance, and multicultural awareness.

Boas stands among the last of the great Renaissance minds. Born in Minden, Westphalia, Germany on July 9, 1858, the son of Meier Boas (a merchant) and Sophie Meyer (a kindergarten founder), he was raised in idealistic German Judaism with liberal and secular values, internalizing democratic and pluralistic beliefs and a strong disdain for anti-Semitism. Challenged by poor health as a child, he embraced books and nature while developing a strong antagonism toward authority. Following education at school and the Gymnasium in Minden, he studied natural history (physics, mathematics, and geography) at the Universities of Heidelberg and Bonn, before studying physics with Gustav Karsten at the University of Kiel, where he received his doctorate (1882). Having developed an interest in Kantian thought during his studies at Heidelberg and Bonn, he pursued study in psychophysics before steeping in geography to explore the relationship between subjective experience and the objective world. This focus of inquiry excited Boas, and in 1883, he began geographical research on the impact of environmental factors on the Baffin Island Inuit migrations. Following the successful defense of his habilitation thesis, Baffin Land, he was named privatdozent in geography at Kiel.

The universality and passionate interest of Boas’s study increased. He continued to study non-Western cultures and published The Central Eskimo (1888), and he worked with Rudolf Virchow and Adolf Bastian in physical anthropology and ethnology at the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin, which directed him toward anthropology. Becoming especially interested in Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest, he traveled to British Columbia in 1886 to study the Kwakiutl Indians. He secured an appointment as docent in anthropology at Clark University (1888), followed by an appointment as chief assistant in anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago (1892). He then received an appointment at the American Museum of Natural History (1895-1905) and began teaching anthropology at Columbia University (1896). In 1899, he was appointed the first professor of anthropology in America, a position he held for 37 years.

The universality and passionate interest of Boas’s study increased. He continued to study non-Western cultures and published The Central Eskimo (1888), and he worked with Rudolf Virchow and Adolf Bastian in physical anthropology and ethnology at the Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin, which directed him toward anthropology. Becoming especially interested in Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest, he traveled to British Columbia in 1886 to study the Kwakiutl Indians. He secured an appointment as docent in anthropology at Clark University (1888), followed by an appointment as chief assistant in anthropology at the Field Museum in Chicago (1892). He then received an appointment at the American Museum of Natural History (1895-1905) and began teaching anthropology at Columbia University (1896). In 1899, he was appointed the first professor of anthropology in America, a position he held for 37 years.

Boas’s contributions to and influence on anthropology and anthropologists are profound. The prevailing sentiment among biologists and anthropologists at the time of Boas’s early work was that a principle of evolution explained why non-Western cultures, especially those inhabitants of microsocieties, were “savage,” “primitive,” and “uncivilized” and composed of “inferior races” compared to Western civilized culture, with superior races. By employing an historical model of reality operationalized by empiricism, Boas developed a scientific anthropology (Boasian anthropology) that rejected theories of sociocultural evolution developed by Edward Burnett Tylor, Lewis Henry Morgan, and Herbert Spencer (“orthogenesis”). He accepted the principle of Darwinian evolution (cultural relativism), which holds that all autonomous human cultures satisfy human needs (and are relatively autonomous), and vehemently argued against the theory of sociocultural evolution that human society evolved in a timeline of stages. Thus, Boas established the historicity of cultural developments and the primary and basic role of culture in human history as well as the relative autonomy of cultural phenomena: Cultures, not culture, are fundamental to the study of man (cultural diversity).

Having realized his life’s goal to study cultural history and learn about peoples, Boas developed and promoted academic and professional anthropology. He was instrumental in modernizing the American Anthropologist and in founding the American Anthropological Association (1902). He reorganized the American Ethnological Society (1900), organized and directed the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, founded and edited the major publications in anthropological linguistics, founded the American Folklore Society and its journal (1888), led the development of anthropology in Mexico, and was active in the development of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists and its journal.

With a vigorous commitment to empiricism, scientific methodologies, and historicity, Boas developed the science of anthropology and transformed the field by basing it on the fundamental conception of cultures as environments of human biological and behavioral life. He reorganized anthropology to include relative autonomy among physical anthropology, archaeology, linguistics, and cultural anthropology (ethnology). The importance of Boas’s work cannot be overestimated: It is of immeasurable historical significance. In physical anthropology, linguistics, and cultural anthropology his theories and findings in field research changed anthropology: Boas’s work became the hallmark of anthropology. He strongly believed in and championed truth.

As a professor of anthropology, Boas had profound influence by mentoring A. F. Chamberlain, A. L. Kroeber, Edward Sapir, A. A. Goldenweiser, R. H. Lowie, Frank G. Speck, Fay-Cooper Cole, H. K. Haeberlin, Paul Radin, Leslie Spier, Erna Gunther, J. A. Mason, Elsie C. Parsons, G. A. Reichard, M. J. Herskovits, Franz Olbrechts, A. I. Hallowell, R. L. Bunzel, M. J. Andrade, George Herzog, Frederica de Laguna, M. Jacobs, Ruth M. Underhill, Gunter Wagner, Jules Henry, Rhoda Metraux, Marcus S. Goldstein, Alexander Lesser, G. Weltfish, M. F. Ashley Montagu, E. A. Hoebel, May M. Edel, Irving Goldman, and the 20th-century anthropological role models, Ruth Fulton Benedict and Margaret Mead. He influenced thousands of students.

Boas’s scholarly publications are quintessential anthropology. His books include The Mind of Primitive Man (1911), Primitive Art (1927), General Anthropology (1938), Race, Language, and Culture (1940), Anthropology and Modern Life (1928, 1962), and The Central Eskimo (1964 paperback). He also published more than 700 monographs and articles, lectured extensively, and accumulated a wealth of field research findings.

As formidable as Boas’s contributions and influences on anthropology and anthropologists were, they were formative to his iconic status. He changed our conception of man by rejecting biological and geographical determinism, specifically racial determinism, and speaking out boldly on cultural relativism and the findings of anthropology to challenge ignorance, prejudice, racism, nationalism, fascism, and war. Boas advanced an internationalism based on the “common interests of humanity” (1928) and combated race prejudice with pioneering antiracist theories. In 1906, W. E. B. DuBois, founder of the Niagara Movement and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), invited Boas to give the commencement address at Atlanta University, where he argued against Anglo-European myths of racial purity and racial superiority, using findings of his research to confront racism.

By studying 18,000 American children of European immigrants, Boas obtained results that showed that biological adaptation (height, weight, head shapes) is a function of environmental factors (diet, lifestyle). These data together with his field research data of the Inuit and Kwakiutl peoples enabled him to champion antiracism long before it was fashionable. To Boas, cultural plurality was fundamental (multiculturalism, cultural diversity). He became a role model for the citizen-scientist, a dedicated humorist with understanding, sympathy, and consideration, who maintained that anthropologists have an obligation to speak out on social issues.

References:

- Goldschmidt, W. R. (Ed.). (1959). The anthropology of Franz Boas: Essays on the centennial of his birth. Menasha, WI: American Anthropological Association Memoirs.

- Herskovits, M. J. (1953). Franz Boas: The science of man in the making. New York: Scribners.

- Hyatt, M. (1990). Franz Boas: Social activist. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Kardiner, A., & Preble, E. (1961). They studied man. Cleveland OH: World Publishing.