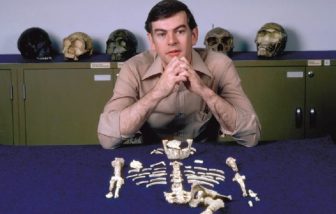

American paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson is most notable for his discovery and interpretation of the fossil hominid Australopithecus afarensis.

Originally born in Chicago, Illinois, of Swedish immigrants, Johnson faced adversity early in life. After the death of his father when Johanson was 2, his mother moved him to Hartford, Connecticut. Johanson’s interest in anthropology was stimulated early in life by Paul Leser, a neighbor who taught anthropology at the Hartford Seminary Foundation. Through exposure to various cultures, Johanson’s interest in our species’ past developed quickly. Although Johanson decided to become an anthropologist in high school, Leser discouraged his anthropological interest in favor of his aptitude in chemistry. Encouraged to pursue science, Johanson attended Illinois State University for chemistry; however, his interest in anthropology grew stronger, eventually leading him to switch majors from chemistry to anthropology, whereby he participated as an archaeologist in the Midwest. Not completely satisfied with the course-work at Illinois, Johanson eventually transferred to the University of Chicago, where he received all of his degrees (BA, MA, and PhD).

In addition to his scholastic endeavors, Johanson was named curator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in 1974 and subsequently developed its affiliated Laboratory of Physical Anthropology. Johanson later relocated to Berkeley, California where he founded the Institute of Human Origins. At this publication date, both Johanson and the Institute of Human Origin are at Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona.

Contributions and Perspectives

Johanson’s most significant contribution was the discovery and interpretation of the fossil hominid, which he named Australopithecus afarensis. Although his first discovery was dubbed “Lucy” during the excavation, the Hadar collection AL 288-1 would prove to be a single specimen that challenges the traditional taxonomical sequence of the human evolutionary line.

Johanson’s most significant contribution was the discovery and interpretation of the fossil hominid, which he named Australopithecus afarensis. Although his first discovery was dubbed “Lucy” during the excavation, the Hadar collection AL 288-1 would prove to be a single specimen that challenges the traditional taxonomical sequence of the human evolutionary line.

Discovered during what could be considered the latter half of the great hominid discoveries, in the early 1970s, Johanson set out to search for fossil hominids in Hadar, Africa. The area of Hadar was perfect for recovering fossils. Hadar was once an ancient lake bed that is now rock, sand, and gravel. Due to the soil’s inability to absorb rainfall, runoff tends to erode the soil, uncovering fossils that lie underneath. Johanson’s first field season at Hadar yielded a proximal tibia, a condyle, and a distal femur. Johanson quickly realized the relationship among the three specimens; discounting human or monkey remains, the knee joint specimen had to be a fossil hominid. Confirmed by Mary and Richard Leakey, this knee joint was the first to be analyzed by anthropologists. An early estimated age of 3 to 4 million years gave Johanson proof of the oldest bipedal specifmen to date, causing debates and a reanalysis of hominid phylogeny.

Although the initial description of this small bipedal creature (for the analysis was far from complete) had yet to gain acceptance by the scientific community represented at the WennerGren conference, the prospect of new hominid began to stir interest. During Johanson’s second expedition to Hadar, he found Lucy at Locality 162. Lucy was described as a three-and-a-half-foot-tall, bipedal hominid with a small brain. Unlike larger jaws found at the site, Lucy’s jaw was V-shaped with one cusp premolar. This fact led Johanson to believe that Lucy was an early representative of australopithecines. This find would only be outdone by the discoveries that followed during the next season.

The third season would prove to be most successful. On a slope known as Site 333, Johanson and his team found bones of what appeared to be a band of hominids who met their demise, only to be uncovered by the eroding rains of Hadar. Although the site lacked animal remains, it yields enough evidence to suggest that these hominids were not related to Lucy, the hominid discovered the previous season. These hominids were considered primitive Homo and dubbed “the First Family.” The fourth season at Hadar was used to recover the remaining fossils for interpretation. Besides the recovery of other fragments including an exquisite jaw, the recovery of stone tools was an additional triumph. Although tools of Oldowan and Acheulean were well known and dated, the tools at Hadar would prove to be nearly impossible to date, leaving much to interpretation in the following months.

Interpretation of Johanson’s evidence created taxonomical issues for the various hominids discovered up to Johanson’s find. Opinions on the placement of this hominid spans the spectrum, creating havoc with the established descent of our own species. The traditional family tree before Johanson’s discovery was A. africanus leading to H. habilis, then H. erectus, ending with our own species H. sapiens. The A. robustus was seen as an extinct branch splitting around 1.5 million years ago; however, Johanson’s discovery of A. afarensis changed that view. With the dating of A. afarensis going back 3.5 million years, the Johanson specimen would be considered the oldest hominid to date. According to Johanson and White, A. afarensis is ancestral to all known hominids. Leading to our species, A. afarensis led to the H. habilis, H. erectus, and H. sapiens (all Homo species having association with tools). On the Australopithecus side, the extinct line leads from A. afarensis to A. africanus, to A. robustus. When considering the age, bipedality, and location, the logical placement of A. afarensis seems to support Johanson’s conclusion. Although there have been more discoveries and phylogenic analysis in recent years, Johanson’s discovery remains an important part of human evolution.

References:

- Edey, M. A., & Johanson, D. C. (1992). Blueprints: Solving the mystery of evolution. New York: Little Brown.

- Johanson, D. C., & Edey, M. A. (1981). Lucy: The beginning of humankind. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Johanson, D. C., & Edgar, B. (1996). From Lucy to language. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Johanson, D. C., & Shreeve, J. (2000). Lucy’s child: The discovery of a human ancestor. New York: Avon.

- McHenry, H. H. (1982). The pattern of human evolution: Studies on bipedalism, mastication, and encephalization. Annual Review of Anthropology, 11, 151-173.

- Skelton, R. R., Mc Henry, H. M., & Drawhorn, G. M. (1986). Phylogenetic analysis of early hominids. Current Anthropology, 27(1), 21-43.