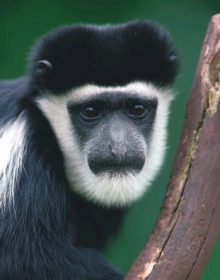

Colobine primates make up one of the two major groups of Old World monkeys. All Old World monkeys are members of a single family, Cercopithecidae, consisting of two subfamilies, Cercopithecinae (the cercopithecines) and Colobinae (the colobines). About 54 species of colobines are currently recognized. Like cercopithecines, colobines are widespread both in Africa and across southern Asia and various islands of the southwest Pacific. They range in size from the West African olive colobus (average adult males 4.7 kg) to Himalayan grey langurs (19.8 kg) and proboscis monkeys (21.2 kg). Most colobines are long-tailed, long-legged, primarily arboreal inhabitants of moist, lowland tropical forests. Most species seldom come to the ground, except to cross openings in the forest. A few species are partly terrestrial; grey langurs of the Indian subcontinent spend up to 80% of the day on the ground and obtain much of their food there.

Food and Digestion

Colobine monkeys differ from cercopithecines in having large, multi-chambered stomachs, an anatomical feature closely related to their behavior and ecology. Anterior sacculations of the fore-stomach are fermentation chambers. They contain bacteria capable of digesting the celluloses and hemicelluloses of dietary fiber. In the forest habitat that most colobines favor, leaves are the most obvious and abundant high-fiber food, and the colobines are sometimes referred to collectively as the “leaf-eating monkeys.” However, the digestive system of colobines does not confine them to a completely folivorous (leaf-eating) diet. Less than a tenth of studied species have diets with more than 30% leaves, and when feeding on leaves, they tend to select the youngest ones. Fruits and seeds/nuts are other major constituents of their diets, making up more than a third of the annual diets of several species. Seed storage tissues, whether carbohydrate or lipid, are richer sources of energy than are young leaves. However, seed storage tissues are also substantially tougher than young leaves. Colobines have molar teeth whose shapes and sizes appear to be well adapted to chewing both leaves and tough seeds.

A second possible function of colobines’ fermentation chambers is that they may lower the gut’s concentrations of various toxic compounds that are produced by plants as a defense against destructive plant eaters. For example, detoxification may account for the ability of purple-faced langurs to eat the toxic fruits of Strychnos trees, which contain toxic alkaloids such as strychnine. Conversely, Strychnos fruits are avoided by toque macaques, which are cercopithecine monkeys that also have access to these fruits but do not have highly developed fermentation chambers in their guts.

The fermentation chambers of colobines enable them to process relatively indigestible forest foliage when other foods are scarce, thus enabling them to attain unusually high biomass. In many forest communities, the biomass of colobine monkeys is greater than that of all other primates combined.

Social Groups

Colobine monkeys of many species live in relatively small social groups, consisting of a single adult male, several adult females, and their offspring. In other colobines, social groups range from small, monogamous associations to groups of over 200 with many adult males. Compared with cercopithecine primates, aggressive and other interactions occur infrequently among females in forest-dwelling colobines. This difference in behavior has been attributed to leaves as a key food resource for many colobines. The abundance and dispersion of leaves within large tree crowns allows several animals to feed together without competition. In contrast, foods of cercopithecine monkeys tend to be more clumped: to occur in smaller, more dispersed patches. In cercopithecines, cheek pouches, which colobines do not have, may be an adaptation to the relatively clumped distribution of fruits and other foods that they commonly eat, enabling them to take quantities of foods into their mouths faster than they can chew and swallow them, thereby reducing competition.

The infrequency of aggressive behavior in colobines may be related to another feature of many species: conspicuous fur color in infants, a common trait in those species in which infants are frequently held and handled by females other than the mother, so-called allomothering. If, when that occurs, mothers can quickly locate and monitor their infants visually, they may be less likely to try to retrieve them.

The infrequency of aggressive behavior in colobines may be related to another feature of many species: conspicuous fur color in infants, a common trait in those species in which infants are frequently held and handled by females other than the mother, so-called allomothering. If, when that occurs, mothers can quickly locate and monitor their infants visually, they may be less likely to try to retrieve them.

Infanticide

After taking over a one-male group, some colobine males kill the infants present in the group at the time. Infanticide in primates was first described among Hanuman langurs by Yukimura Sugiyama in 1965. It has since been reported in a wide variety of other primates and various other mammals. In langurs, it has been regarded by some as a social pathology, an accidental by-product of heightened aggression resulting from higher population densities in populations provisioned by humans. Others consider it a sexually selected adaptation, a male reproductive strategy, in that without a nursing infant, females come into estrus sooner. This would thereby increase the new male’s breeding opportunities, particularly if the new male, in turn, might otherwise be deposed before any females have come into estrus. However, this would not be the case in seasonal breeders, in which the male would, in either case, have to wait until the next breeding season. Thus, any reproductive advantage to the males of being infanticidal would depend on the distribution of males’ takeover times relative to breeding seasons, the distribution of males’ tenure in groups, and a propensity to kill the infants of other males but not their own. In 1999, Carola Borries and her colleagues, using DNA analysis to determine langur paternity, presented the first evidence that male attackers were not related to their infant victims, and in all cases, they were the likely fathers of the subsequent infants. This study strongly supports the interpretation of infanticide as an adaptive male reproductive tactic.

Of course, for infants and their deposed fathers, infanticide is clearly disadvantageous. For mothers, it may not be from the standpoint of their biological fitness—not, for example, if the greater toughness and aggressiveness of the deposing male is inherited by the sons that he sires. If, as adults, these new sons breed more successfully, then more of their mothers’ genes may be passed on to future generations than if their sons by the deposed male had survived.

References:

- Davies, A. G., & Oates, J. F. (Eds.). (1994). Colobine monkeys: Their ecology, behaviour, and evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lambert, J. E. (1998). Primate digestion: Interactions among anatomy, physiology, and feeding ecology. Evolutionary Anthropology, 7, 8-20.

- Van Schaik, C. P., & Janson, C. H. (Eds.). (2000). Infanticide by males and its implications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.