The word class comes to us from the Latin classis, which referred to the division of Romans according to property. It takes on its modern sense in English from the late 18th century, when the profound sociopolitical upheavals associated with the French and Industrial Revolutions redrew the social map of Europe. Prior to this time “rank,” “estate,” and “order” were more commonly used to speak of the exploitative self-differentiation of society into functionally interrelated and hierarchically organized sociocultural groupings. Subsequently, most of these meanings were subsumed within “class,” though precisely with the difference that the term no longer automatically connoted a natural or divinely ordained social layering.

Given this volatile history, it is no surprise that there has been little consensus on the definition or even existence of classes. Indeed, it has been argued that class is so hard to define because the meaning of the concept is itself a stake in class struggles. Naturally, many would disagree (perhaps thereby proving the original point).

These conceptual tensions are in play in the anthropology of class and class societies, along with an additional problem. The word, together with its contested meanings, carries the birthmarks of the European sociocultural realm from which it sprang. How then are anthropologists to treat the question of class?

Three basic options may be mentioned. Class can be quietly set aside as insignificant for anthropology on the grounds that the comparatively economically undifferentiated societies traditionally studied by ethnographers are not class societies. Alternatively, class can be employed, but within a restricted compass. Finally, the concept can be wrestled into a new form in the attempt to make it adequate for various kinds of non-Western societies.

The principal social scientific approaches to class have come out of political economy, sociology, and above all, Marxism. For Karl Marx (1818-1883), to speak of classes was to speak of distinct groups of people defined by their ownership and control over productive property or by their lack of it. Class division was the defining aspect of any complex social order and the ruling ideas the ideas of the ruling class.

Neither this, nor any other conception of class, has been central to the main current of anthropological thought. Where appeal has been required to kindred phenomena, categories like stratification, status group, and hierarchy coming out of the Weberian tradition have often been found more serviceable. It is a moot point, however, whether this has been a matter of choosing concepts most appropriate to non-Western societies, as thinkers like Louis Dumont (1911-1998) have argued, or of ignoring class, as Talal Asad has charged.

The point proved especially moot from the mid-1960s on, as increasing political militancy both at home and in the newly postcolonial countries radicalized many anthropologists. Their discipline, some came to think, had historically made class politics disappear behind dubious assumptions about order and consent in traditional non-Western societies.

The evolutionary model of 19th-century anthropology, and the work of Lewis Henry Morgan (1818-1881) in particular, had an ambiguous effect in this regard. To the one side, it furnished arguments accounting for the historical emergence of property-owning classes. To the other, it suggested that the most primordial societies would be classless. The latter was a logical if not an empirical requirement of the model, since class is a social differentiation, and by definition the undifferentiated ultimately predates that which is differentiated. With this supposition in hand, “survivals” of classlessness could be freely discerned in existing “primitive” societies.

Certain major anthropological thinkers in the first half of the 20th century could also be seen to have reinforced a similar result, if from different starting points. Franz Boas (1858-1942) emphasized the study of particular cultures as integrated wholes arising from discrete histories. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) viewed each society as a composite of parts geared to meeting the biological needs of the individual. A. R. Radcliffe-Brown (1881-1955) conceived of societies as functional units regulated by general laws oriented to ongoing social reproduction. From angles like these, it would be argued, class relations had little chance of getting the attention they deserved.

Certain major anthropological thinkers in the first half of the 20th century could also be seen to have reinforced a similar result, if from different starting points. Franz Boas (1858-1942) emphasized the study of particular cultures as integrated wholes arising from discrete histories. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) viewed each society as a composite of parts geared to meeting the biological needs of the individual. A. R. Radcliffe-Brown (1881-1955) conceived of societies as functional units regulated by general laws oriented to ongoing social reproduction. From angles like these, it would be argued, class relations had little chance of getting the attention they deserved.

A shared desire to champion the interests of exploited classes, however, has been no guarantee of unanimity on the question of the presence or absence of classes in non-Western societies. Ambiguity on this issue was a feature even of the Marxist classics. Friedrich Engels (1820-1895) would famously come to modify the Communist Manifesto s (1848) declaration that the history of all hitherto existing society was the history of class struggles. In footnotes to later editions, the claim was qualified to cover only the period of written history. Prior to that time, there was little reason to credit the existence of property-owning classes. Moreover, Marx and Engels were alert to the continuing significance of common ownership in societies that had not yet come fully under the domination of the bourgeoisie.

In their wake, as Yuri Slezkine has detailed, early 20th-century Soviet anthropologists and ethnologists confronted the same dilemma in quite concrete circumstances. They could go hunting for evidence of survivals of primeval common ownership among the “small peoples” of the Soviet Union, or they could seek out disguised forms of class oppression on behalf of indigenous proletariats. In the West, Eleanor Burke Leacock (1922-1987) argued the case for a long era of «primitive communism” prior to the emergence of class societies, while Emmanuel Terray claimed that age and sex could function as classes in precapitalist social formations.

The positions argued by Leacock and Terray, respectively, though both drawing on Marxism, represent two opposed views of the remit of class. Leacock’s approach has Marxist tradition on its side. Heavily influenced by Morgan’s Ancient Society (1877), this tradition underlines the egalitarian nature of early kinship societies and typically conceives of the production of goods as determined by requirements of use. With increases in the productivity of labor, surpluses become available for differential appropriation. This in turn makes possible the emergence of ruling classes utilizing elements of a nascent state to put others to work for them.

One possible problem with this approach, as Maurice Bloch has emphasized, is that Marxism, having made class the linchpin of its theory of society, winds up having little distinctively Marxist to say about apparently classless societies. Instead, it merely reproduces the untenable arguments of 19th-century anthropology about “primitive” society.

An alternative is to dispense entirely with the evolutionary framework and the requirement it imposes to work out which of the canonical “stages” of the organization of the mode of production any given society falls within. This is the option pursued by structuralist Marxists like Bloch, Maurice Godelier, and Terray himself. The difficulty faced by this disparate group was that Marx’s categories of thought were generated to explain European capitalist society. Their task, therefore, entailed identifying and extracting those elements of Marxist theory that might promise to be of universal applicability. For some, like Terray, class was one of those elements and could now be extended to understand unequal and exploitative relations in all societies. Others, notably Godelier, have been less than happy with discovering classes among peoples who have, and can have, no intimation of such a thing.

The general question raised by such concerns is a classic one: May we speak of “class society” if and only if people self-consciously define themselves as belonging to a class? Or can class exist as a deep structure, the “hidden secret” of the social order?

In general, it has been easier to argue the reality of class as an objective or “etic” social relation within existing non-Western kinship societies than as an intraculturally recognized or “emic” one. Or at least it has been plausible to make such etic claims within the spatiotemporal catchment area of European world expansion. Tangled in a planetary net of someone else’s making, tribal, band, and rural peoples end up producing primary commodities for international markets; being answerable to local and national military-governmental structures; living off royalties from mining or forestry on their shrinking lands; and consolidating internal elites owing much of their status to monopolistic control over external sources of wealth. But it is another matter altogether that these subjugated peoples should come to see themselves as members of a class. And it is yet a further step that they should define their corporate interests as hostile to that of another class.

Such dilemmas become exacerbated when radical ethnographers attempt to put themselves at the service of nonexistent class struggles. The Africanist Wim van Binsbergen, for example, confronted this situation with the Nkoya of Western Zambia. Van Binsbergen hoped that his analyses of the economic and political condition of the Nkoya might encourage some of them to become militant and class conscious. The Nkoya, however, stubbornly regarded his ethnography as an opportunity to codify their history as a distinct people and bring credit to the splendor of their chieftainship.

Sobering experiences such as van Binsbergen’s are no doubt only one among many of the reasons for the current receding tide of confident Marxist writings on class within anthropology. More recent work, such as that by Brackette Williams or Donna Goldstein, tends rather to tackle class while in the pursuit of other themes, commonly race, ethnicity, sexuality, and gender.

References:

- Asad, T. (1972). Market model, class structure and consent: A reconsideration of swat political organization. Man, New Series, 7(1), 74-94.

- Bloch, M. (1983). Marxism and anthropology: The history of a relationship. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dumont, L. (1970). Homo Hierarchicus. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Godelier, M. (1978). Infrastructures, societies, and history.

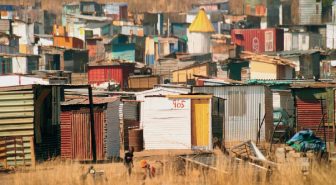

- Goldstein, D. M. (2003). Laughter out of place: Race, class, violence and sexuality in a Rio shantytown. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Leacock, E. (1954). The Montagnais “hunting territory” and the fur trade. American Anthropologist, 56(5) Part 2, Memoir 78.

- Morgan, L. H. (1963). Ancient society: Researches in the lines of human progress from savagery through barbarism to civilization. New York: Meridian Books. (Original work published 1877)

- Slezkine, Y. (1991). The fall of Soviet ethnography, 1928-38. Current Anthropology 32(4), 476-484.

- Terray, E. (1975). Class and class consciousness in an Abron kingdom of Gyaman. In M. Bloch (Ed.), Marxist analyses and social anthropology (pp. 85-135). London: Malaby Press.

- Van Binsbergen, W. M. J. (1984-2002). Can anthropology become the theory of peripheral class struggle? Reflections on the work of Pierre-Philippe Rey.

- Williams, B. F. (1989). A class act: Anthropology and the race to nation across ethnic terrain. Annual Review of Anthropology, 18,401-444.