Since the Industrial Revolution, most Western societies have come to consider childhood as a time of innocence rooted in biological processes that gradually progress from infancy, childhood, and adolescence into adulthood. In this concept, all youth are defined as minors who are dependent upon adult guidance and supervision; accordingly, youth are denied legal rights and responsibilities until they reach the age that legally defines adulthood. Progressive social scientists view childhood as a concept dependent upon social, economic, religious, and political environments. Rather than see childhood as a time of nonparticipation and dependence, social constructionists see childhood as an expression of society and its values, roles, and institutions. In this sense, childhood is conceptualized as an active state of participation in the reproduction of culture. Indeed, constructionist views of childhood state that childhood is not a universal condition of life, as is biological immaturity, but rather a pattern of meaning that is dependent on specific sets of social norms unique to specific cultural settings.

Childhood can be characterized as the interplay and conflict of and between institutions, individuation, and individualization. Childhood is positioned within this triangulation, revealing how institutions such as day care and kindergarten are rooted in women’s labor issues, creating a pull between the pedagogical needs of children versus the economic needs of adults. Individuation is the process by which individuals become differentiated from one another in society. This process identifies childhood as the target for the attention of the state and produces institutions and care providers who delimit the individuality of children. Therefore, a basic tension exists between individual development and collective needs, between the real needs of children and the economic and political needs of adults. Hence, childhood is kept within specific boundaries defined by institutions administered by adults. Therefore, children can be seen to be at the beginning of the process of individualization, long ago achieved by men and only recently achieved by women.

It has been suggested that childhood constitutes a social class, in that children are exploited in relation to adults, who determine and define the needs of childhood according to adult terms. This forces us to place the analysis of childhood in a political-economic frame and shows how children are actually buried in the ongoing division of labor within the adult world.

Childhood Reflects Structures of Power and Domination

The Industrial Revolution in 19th-century Europe resulted in major transformations in economic and social relations. These transformations resulted in the concentration and penetration of capital, which generated two distinct classes: bourgeoisie and proletariat. With this transformation, we see the separation of childhood as distinct from adulthood. Children were differentially affected by industrialization according to class and family relations. Innocence, purity, protection, and guidance define the children of the bourgeois class, while children of the proletariat were considered to be miniature adults who constituted a reserve pool of labor power in early and middle industrial capitalism. Children of the upper classes received private education that trained them for positions of leadership and power, while children of the working class were often put to work alongside adults in factories and sweatshops in industrial Europe.

The Industrial Revolution in 19th-century Europe resulted in major transformations in economic and social relations. These transformations resulted in the concentration and penetration of capital, which generated two distinct classes: bourgeoisie and proletariat. With this transformation, we see the separation of childhood as distinct from adulthood. Children were differentially affected by industrialization according to class and family relations. Innocence, purity, protection, and guidance define the children of the bourgeois class, while children of the proletariat were considered to be miniature adults who constituted a reserve pool of labor power in early and middle industrial capitalism. Children of the upper classes received private education that trained them for positions of leadership and power, while children of the working class were often put to work alongside adults in factories and sweatshops in industrial Europe.

Economics

A key step in redefining childhood beginning in the mid-1800s was the removal of children from the public sphere. The state, religious, and civil societies each had particular interests in redefining childhood and in removing children from their exposure to the adult world. Growing industrialism demanded an unimpeded free labor market, where child labor was plentiful and cheap. However, toward the end of the 1800s, new reformist attitudes about the detrimental effects of child labor were forming. Protestant Christians and social reformers’ concerns about the physical and emotional hazards of child labor helped to initiate the welfare movement and led to debates about the desirability and feasibility of controlling the child labor market.

Childhood Changes Culturally

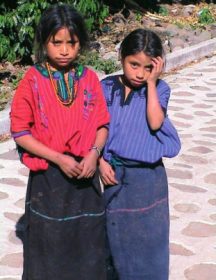

Conceptualizing childhood in diverging cultural settings requires an anthropological perspective that sees children and childhood as windows into societies. Unfortunately, anthropologists have not taken childhood and children seriously enough, focusing instead on adult society as the locus of interest and change.

Currently, there is a growing movement in social science to view children as active agents who construct meanings and symbolic forms that contribute to the ever-changing nature of their cultures. Not only are children contributing to the complex nature of cultural reproduction, they are accurately reflecting the unique nature of their specific culture.

Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa (1928) explored the theoretical premise that childhoods are defined by cultural norms rather than by universal notions of childhood as a separate and distinct phase of life. The term youth culture was introduced in the 1920s by Talcott Parsons, who defined the life worlds of children as structured by age and sex roles. Such a definition marginalized and deindividualized children. The work of Whiting and Edwards, during the 1950s to late 1970s, in diverse cultural settings, developed methodologies to explore what they exemplified as cross-societal similarities and differences in children. Their attempts at producing a comprehensive theory about childhood development, cognition, and social learning processes were informative and groundbreaking. Their work linked childhood developmental theories to cultural differences, demonstrating that children’s capacities are influenced as much by culture as by biology. By the 1980s, social research had moved into predominately urban studies, where youth groups and gangs were conceptualized and defined by American sociologists as deviants rebelling against social norms. Current authors such as Qvortrup, Vered Amit-Talai, Wulff, and Sharon Stephens are recasting global research on childhood by defining children as viable, cogent, and articulate actors in their own right. Such research has spawned strident debates concerning the legal rights of children versus the legal rights of parents.

Managing the Social Space of Childhood

Reform of child labor laws required that the needs of poor families, reformers, and capitalists be balanced. In this equation, public education became a means by which children could be removed from the public sphere and handed over to the administrative processes of the state. Statistics from the late-19th-century censuses reveal the effectiveness of the reformers: In England, by 1911, only 18% of boys and 10% of girls between the ages of 10 and 14 were in the labor market, compared with 37% and 20%, respectively, in 1851. Economically, children moved from being an asset for capitalist production to constituting a huge consumer market and a substantial object of adults’ labor in the form of education, child care, welfare, and juvenile court systems. Although reformers and bureaucrats could claim a successful moral victory in the removal of child labor from the work force, in reality, children had been made superfluous by machinery and the requirement that industrial work be preserved for adult male and female laborers. In this respect, culture is not only perpetuated by children, but changed by it. The late-modern constructions of childhood acknowledge that children are placed and positioned by society. The places that are appropriate for children to inhabit have widened, and children are now seen as targets of media and marketing campaigns, though children as individuals and as a class have few legal rights.

The definitions of childhood as a state of innocence and purity follow long historical cycles of economic change that correspond to the development of capitalism as it spread within the world system. Immanuel Wallerstein’s world systems theory describes historical economic relations in terms of exchanges between the core, semiperiphery, and periphery states. The evaluation the role of children in the world system has led to an agreement by many social scientists that childhood is historically and culturally relative. Recent anthropological political economy theory demonstrates how relations between nation-states and the development of capitalism affect growing child poverty. In addition, these relations determine the role of children economically, socially, and educationally throughout the world, affecting policy development at both the state and federal levels, particularly in the areas of child poverty and child development. Social scientists should turn their attention to a generational system of domination analogous to the gendered oppression that has captured the attention of feminist scholars for the last several decades. If successful, this agenda will advance the legal status of childhood globally, freeing future generations to participate as viable actors within political, economic, and legal realms within their unique cultures.

Recent research on street children around the world demonstrates that childhood is a social construction dependent on geographical, economic, ethnic, and cultural patterns. Patricia Marquez, in The Street Is My Home (1999), explored how street youth in Caracas, Venezuela, are brought together because of economic scarcity and social violence, by describing the ways in which these youth are able to gain financial resources and material wealth through the creation of meaningful experiences and relationships in their lives. Tobais Hecht, in At Home in the Street (1998), portrayed street children in Recife as socially significant themselves, acting as both a part of and a reflection of the concerns of adults. He found that Recife’s street children took pride in working and earning an income.

Social reality may be seen as a process of constructing one’s social world through the skillful actions of everyday life. Alongside the development of the constructionist view of race, gender, and ethnicity, childhood is simultaneously viewed as dependent on location. Historically, theoretical views of childhood have profoundly affected how children are positioned socially, politically, economically, medically, and legally. Due to the recognition of the ways in which both popular and academic views of childhood have impacted children, recent social science research now seeks to redefine childhood as a time of agency and self-directed learning and participation in society, while developing new theoretical paradigms that view children as subjects worthy in their own right, not just in their social status as defined by adults.

References:

- Amit-Talai, V., & Wulff, H. (Eds.). (1995). Youth cultures: A cross-cultural perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Blanc, S. C. (1994). Urban children in distress: Global predicaments and innovative strategies. Grey, Switzerland: Gordon & Breach.

- James, A., & Prout, A. (1997). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. London: Falmer Press.

- Mickelson, A. R. (2000). Children on the streets of the Americas. New York: Routledge.

- Qvortrup, J., Bardy, M., Sgritta, G., & Wintersberger, H. (Eds.). (1994). Childhood matters: Social theory, practice, and politics. Brookfield, VT: Avebury.

- Rogers, R., Rogers, S., & Wendy, S. (1992). Stories of childhood: Shifting agendas of child concern. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Scheper-Hughes, N., & Carolyn S. (Eds.). (1998). Small wars: The cultural politics of childhood. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stephens, S. (1995). Children and the politics of culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.