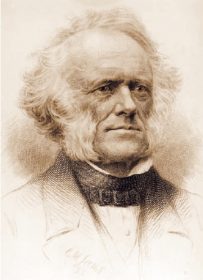

Charles Lyell was born in Kinnordy, Forfarshire, Scotland, on November 14, 1797, the eldest of 10 children. His father guided his early studies of nature, but Lyell’s formal education was received at Exeter College of Oxford University. While there, Lyell was influenced by the works of William Buckland, a geologist and paleontologist. After graduating in 1816, Lyell studied law, but by 1827 he had abandoned the profession to start a long, full-time career in geology. His writings would enhance the ideas proposed by James Hutton, a Scottish geologist considered by many to be the father of modern geology and noted for formulating the concepts of uniformitarianism, in his Theory of the Earth (1795) as well as the Plutonists’ school of thought. Hutton’s new theory was based on his observations that layers of sedimentary rocks, thrust up against other layers at various angles, pointed to the fact that layers had been deposited, transformed into rock, and then tilted only to have further deposition on top. He also proposed that the interior of the earth was hot and that the movement in this “heat engine” resulted in the formation of new rock. The presumption was that these tremendous displacements of rock happened gradually, requiring a vast amount of time to slowly produce the various topographies. A corollary to his argument was that the same geological processes at work today were in operation in the past, whereas the prevalent notion at the time was catastrophism, which stated that all rocks had precipitated out of an enormous flood in a very short time span. Hutton’s view of the geology of the earth had “no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.”

Lyell was also committed to this steady-state, nondirectional, and nonprogressive view of unifor-mitarianism. Changes were gradual and continuous, but with no direction. He rejected Hutton’s thesis that the earth had been molten when it was first formed and that it was in the process of cooling. This denial posed a serious impediment by ignoring the relevance of astronomy and physics to historical geology.

Lyell was also committed to this steady-state, nondirectional, and nonprogressive view of unifor-mitarianism. Changes were gradual and continuous, but with no direction. He rejected Hutton’s thesis that the earth had been molten when it was first formed and that it was in the process of cooling. This denial posed a serious impediment by ignoring the relevance of astronomy and physics to historical geology.

From 1830 to 1833, Lyell published his three-volume Principles of Geology. The work’s subtitle was An Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface by Reference to Causes Now in Operation. However, it restricted all geological explanations to causes that can be observed in the present, ruling out any catastrophies because they are non-observable in the present, and therefore rejecting them as past events to explain the present formations.

Lyell believed in the uniformity of the laws of nature, as did the catastrophists. His position may be summarized by pointing out not only that geology was to restrict its hypotheses to the same kind of causes as those currently acting but also that the intensity of those causes is to be in the same range that currently exerts itself. This view of uniformitarianism rules out the possibility of a developmental theory of the earth.

Lyell’s Principles of Geology, and its many revisions, was the most influential geological work of its day and did much to lay the groundwork for the fledgling science of historical geology.

Another important area of geological endeavor was in the field of stratigraphy, a branch of geology concerned with the relationship between sedimentary rocks and their depositional environment. As a result of his fieldwork in Italy and France, Lyell was able to categorize recent strata by kind and proportion of fossil marine organisms, resulting in his proposed division of the Tertiary Period into three segments that he named the Pliocene, Miocene, and Eocene. The second edition of his Principles of Geology explained new ideas concerning metamorphic rocks. It delineated the rock changes due to high temperatures in sedimentary rocks adjacent to igneous rocks.

The impact of Lyell’s geological uniformitarianism on Charles Darwin was significant and had staggering results. Darwin read the Principles of Geology during his 5-year voyage on the HMS Beagle. It provided Darwin with the background to contemplate those formations that could result in geology by small and slow processes operating over immense periods of time. Darwin’s early papers were, in fact, attempts to explain geological and biological features (i.e., his coral reef work) in a uniformitarianistic manner. His later On the Origin of Species (1859) relied on these same premises.

Although Lyell inspired Darwin and became his lifelong friend and mentor, his approach in applying the principles of uniformitarianism in a steady-state, nondirectional, nonprogressive world to the history of living organisms put him in initial disagreement with Darwin the evolutionist. Lyell maintained that the fossil record had no development from simple organisms to more complex ones because the earth always has sustained the full range of living organisms, even predicting that the fossils of mammals could be found in the oldest sedimentary rocks. He believed in the fixity of species, although he acknowledged that many new species had become extinct and that all ecological niches were always occupied with many new species coming into existence, but not something observable in the present. He refused to specify how or what he meant, leaving the interpretation open to discussion.

Later in his life, Lyell acknowledged the accumulation of evidence regarding the evolution of organisms over time and became one of the first prominent scientists to endorse On the Origin of Species, although he never fully accepted natural selection as a driving mechanism behind evolution in his public writings. In 1858, Lyell was in fact instrumental in arranging the copublication of the theory of natural selection by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Darwin had withheld publication of his accumulated evidence regarding natural selection for more than two decades. He was forced into publication due to the independent discovery of a similar theory by Wallace, who sent Darwin his paper titled “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Originality from the Original Type.” In 1863, Lyell published his Geological Evidences as to the Antiquity of Man, discussing Darwin’s theory at length.

For his contributions to the science of geology, Lyell was knighted in 1848 and was made a baronet in 1864. He died on February 22,1875, and is entombed in Westminster Abbey, as is Charles Darwin.

References:

- Lyell, C. (1873). Principles of geology (Vol. 1). New York: D. Appleton.

- Ruse, M. (1976). Charles Lyell and the philosophies of science. British Journal for the History of Science, 9, 121-131.

- Wilson, L. G. (1972). Charles Lyell: The years to 1841—The revolution in geology. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.