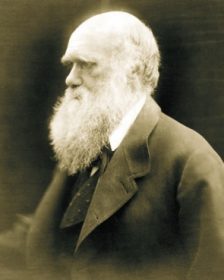

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882) is one of the greatest naturalists in the history of science. His theory of organic evolution delivered a blow to traditional thought by offering a new worldview with disquieting ramifications for understanding and appreciating the human species within natural history. The geobiologist had presented his conceptual revolution in terms of science and reason (i.e., his evolutionary framework is based upon convincing empirical evidence and rational arguments). As a result of Darwinian evolution grounded in mechanism and materialism, philosophy and theology would never again be the same; just as the human species is now placed within primate history in particular and within the organic evolution of all life forms on this planet in general, religious beliefs and practices are now seen to be products of the sociocultural development of human thought and behavior.

The implications and consequences of biological evolution for the human species were both far-reaching and unsettling. It is no surprise that the brute fact of organic evolution disturbed Darwin himself, because he had been trained in theology at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he had become interested in William Paley’s Natural Theology (1802). A strictly mechanistic and materialistic view of the emergence of humankind in terms of evolution challenged the most entrenched religious beliefs, for example, the existence of a personal God, human free will, the personal immortality of the soul, and a divine destiny for moral persons: If evolution were a fact, then the human animal would be an evolved ape, not a fallen angel.

Naturalists were becoming aware of the unfathomable age of this planet. Incomplete as they were (although ongoing scientific research is closing the gaps), the geological column and its fossil record argued for the heretical idea that species are, in fact, mutable throughout organic history.

Naturalists were becoming aware of the unfathomable age of this planet. Incomplete as they were (although ongoing scientific research is closing the gaps), the geological column and its fossil record argued for the heretical idea that species are, in fact, mutable throughout organic history.

For the theist, this universe was created by, is sustained by, and will be completed by a personal God, a perfect being that loves our species as the cosmic center of His divine creation. It is impossible, however, to reconcile materialistic evolution with traditional theology; science and reason have challenged the belief that earth history and the process of evolution are the result of a preestablished plan within the alleged order and design of this dynamic universe. Consequently, it is not surprising that some biblical fundamentalists and religious creationists reject the scientific theory of organic evolution and desire to discredit it and prevent both evolutionary research and the teaching of evolution. For others, it takes an extraordinary leap of faith and speculation to believe that a personal God could be both the beginning and the end of cosmic evolution. Biological evolution is a process that is long and complex, with pain and suffering as well as death and species extinction (five recorded mass extinctions on a global scale) pervading organic history, not to mention the endless appearance of deleterious mutations involving physical characteristics and behavior patterns. Surely, philosophy and theology now have a difficult time in maintaining teleology and essentialism as built-in aspects of cosmic evolution in general and the emergence of life forms (including the human animal) in particular.

Darwin was the pivotal thinker in establishing the fact of evolution. His heretical theory shifted an interpretation of this world from natural theology to natural science, a direct result of giving priority to empirical evidence and rational argumentation rather than to faith and belief. It was Darwin’s naturalistic orientation that led him to explain evolving life forms in terms of science and reason, an interpretation independent of theology and metaphysics.

Discovering Evolution

The young Darwin was interested in geology and entomology; he enjoyed studying rocks, collecting beetles, and taking field trips with accomplished naturalists. But over the years, his primary interest would shift from geology to biology, and he came to doubt both the fixity of species and the biblical account of creation. There was no early indication of his genius for descriptive and theoretical science. Yet a convergence of ironic and fortuitous events over a period of 7 years would result in his theorizing that all species are mutable in nature and slowly evolve (or become extinct) due to natural causes over vast eons of time.

How was Darwin able to deliver this blow to traditional thought in terms of evolution? For one thing, the young naturalist had a free, open, curious, and intelligent mind that had not been indoctrinated into any religious creed or philosophical framework. That is to say, he was able to reinterpret the living world in terms of his own experiences (unique events that were critically examined in terms of science and reason). Darwin also had an exceptional ability to analyze natural objects (orchids, barnacles, and earthworms), as well as to synthesize vast amounts of empirical evidence into a comprehensive and intelligible view of organic history. Furthermore, he had an active but restrained imagination that allowed him to envision the process of biological evolution gradually taking place over vast periods of time as a result of natural forces.

Besides his unique psychological makeup, Darwin was greatly influenced by the writings of Charles Lyell, whose three-volume work, Principles of Geology (1830-1833), placed historical geology on a scientific foundation. While reading the entire work during his trip as naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle, Darwin slowly accepted Lyell’s sweeping geological framework of time and change within a naturalistic viewpoint of earth history. One may even argue that Lyell was the single most important influence on Darwin because without this vast temporal perspective, the geobiologist might never have questioned the eternal fixity of species or, subsequently, thought about life forms in terms of their mutability throughout organic history. Simply put, the dynamic framework of Lyellian geology, with its changing environments, implied a process view of plants and animals. Having become convinced that Lyell was right, Darwin then began both to doubt a strict and literal interpretation of Genesis and to question more and more the alleged immutability of flora and fauna types on this planet. Briefly, Lyell’s dynamic interpretation of rock strata throughout geological history clearly argued for an evolutionary interpretation of life forms throughout biological history.

Another major influence on Darwin’s worldview was, of course, his voyage of discovery on the HMS Beagle. During this 5-year circumnavigation of the globe (1831-1836), the young naturalist experienced the extraordinary diversity of plant and animal species in the Southern Hemisphere (particularly the insects of a Brazilian rain forest) as well as the provocative discovery of giant fossils in the geological column of Argentina. Slowly, he began to imagine the tree or coral of life throughout organic history. Of special importance was Darwin’s comparing and contrasting life forms on oceanic islands with their counterparts on the mainland of South America. He was struck not only by their differences but also even more so by their similarities. These similarities suggested that groups of species share a common ancestor. Thus, throughout space and time, Darwin envisioned the historical continuity and essential unity of all life on this planet. Certainly, in retrospect, it was his 5-week visit to the Galapagos Islands (September 15 to October 20, 1835) that caused this naturalist to acknowledge the crucial relationship between the physical characteristics and behavior patterns of an organism and its specific habitat.

No doubt, Darwin was puzzled by the belief that a personal God had created so many different species of a specific animal form for the same archipelago: Why would there be different species of finches, mockingbirds, tortoises, and iguanas throughout the Galapagos Islands? For Darwin, the obvious answer, supported by the empirical evidence, is that there was neither a single divine creation only 6,000 years ago nor a sequence of special creations over this same period of time. Instead, science and reason argued for a natural (not supernatural) explanation for the origin, history, diversity, and extinction of life forms on the changing earth.

Darwin was willing to doubt the myth of Genesis, while taking seriously both the new facts and the new concepts in several earth sciences (geology, paleontology, biogeography and comparative morphology). At the end of the voyage, he was convinced that species are mutable and began to keep notebooks on his theory of “descent with modification”—an evolutionary interpretation of organic history. Unfortunately, he did not as yet have an explanatory mechanism to account for biological evolution in terms of a naturalistic framework. Nevertheless, he steadfastly committed himself to the mutability of species as an incontrovertible fact of the living world.

In 1838, by chance, Darwin read Thomas Malthus’s scientific monograph, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798, 1803), which described life as a struggle for existence. According to Malthus, this ongoing struggle for survival in nature results from the discrepancy between the arithmetic increase of plants and the geometric increase of animals (especially the human species). Malthus’s book gave the naturalist his major explanatory mechanism of natural selection or the “survival of the fittest” (as the philosopher Herbert Spencer had referred to it). Now, Darwin had both a theory and a mechanism to account for the history of life on earth: The scientific theory is organic evolution, while the explanatory mechanism is natural selection. This was a strictly mechanistic and materialistic interpretation of the biological world.

Admittedly, Darwin himself was concerned neither with the beginning of this universe and the origin of life nor the future of our species and the end of the world. He left it to other thinkers to grapple with those philosophical questions and theological issues that surround the scientific fact of organic evolution.

Darwin’s Thoughts

In the first and second editions of On the Origin of Species (1859), Darwin did not refer to God as the creator of the world. But encouraged to do so by the geologist Lyell, the last four editions of the Origin volume contained only one simple reference to God:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.

Nonetheless, Darwin’s Autobiography makes it perfectly clear that he was publicly an agnostic (if not privately an atheist). Briefly, Darwin’s own cosmology is agnostic, while his theory of evolution is atheistic.

Realizing how disturbing his epoch-making Origin book would be, Darwin did not wish to add to the growing controversy surrounding biological evolution by writing about the emergence of our own species. Interestingly enough, then, Darwin does not discuss human evolution in his major work on the theory of evolution. In fact, one may argue that it was the devastating ramifications of organic evolution for the human animal that actually caused the uproar over Darwinian evolution.

Grappling with the implications of evolution, Thomas Huxley in England coined the word “agnostic” to express his own noncommittal position concerning the existence of God, while Ernst Haeckel in Germany advocated pantheism to express his dynamic world-view free from religion and theology. In doing so, both naturalists had acknowledged that the scientific fact of organic evolution has wide-ranging conclusions for those entrenched values of Western civilization that are grounded in traditional philosophy, religion, and theology. At Harvard University, the botanist Asa Grey supported theistic evolution.

For over a decade, even Darwin himself had been reluctant to extend his theory of evolution to account for the origin and history of the human species. After 12 years, he published his other major work, The Descent of Man (1871). It is in this book that the naturalist writes about human evolution, although both Huxley as comparative morphologist and Haeckel as comparative embryologist had already lectured on and written about the evolution of our species within the history of the primates.

Darwin wrote that the human animal is closest to the African pongids, the chimpanzee and the gorilla (the existence of the bonobo was unknown to the naturalists of that time). He held that our species and these two great apes share a common ancestor, which would be found in the fossil record of that so-called Dark Continent, which has, since the middle of the 20th century, shed so much light on the history of humankind. Moreover, Darwin claimed that the human species differs merely in degree, rather than in kind, from the pongids, there being no structure or function in the human animal that does not already exist to some degree in the three great apes known to him (orangutan, gorilla, and chimpanzee). That is to say, even intelligence and emotions exist to some degree in all the pongids, which now include the bonobo.

For Darwin, it was the moral aspect in the human being that elevates it above—but does not separate it from—the apes. Even so, this moral aspect has also evolved throughout primate history from even lower beginnings, in earlier animals. Philosophers and theologians cannot ignore the reality that human beings themselves have created ethics, morals, and values within a natural environment and sociocultural milieu; one may speak of a human being as the evaluating animal, thereby distinguishing the human species from all the apes and monkeys.

Likewise, Darwin claimed that the naturalistic basis of human morality had had its origin in those social instincts and altruistic feelings that have enhanced the adaptation and reproduction of evolving fossil apes, and later protohominids, followed by bipedal hominids. These instincts and feelings are visible in the behavior patterns of living primates, particularly in the great apes.

The Evolutionary Worldview

Clearly, scientific evolution both challenged and super-seded the ideas and frameworks of Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes, Kant, and Hegel (among many others). The certainty of previous values grounded in God-given laws or divine revelations could no longer be upheld by rigorous naturalists. As a result, the Darwinian conceptual revolution in science resulted in the emergence of both evolutionary ethics and pragmatic values in modern natural philosophy, as well as an evolutionary interpretation of the origin and history of human societies and their cultures (including languages and beliefs).

For the rigorous scientist, evolution requires at least reinterpreting or rejecting the old beliefs in God, free will, immortality, and a divine destiny for our species. For decades, ongoing evolutionary research in the areas of paleoanthropology and primate ethology has clearly supported the fact of human evolution, as well as a naturalistic explanation for the so-called brain/mind problem in philosophy.

It is not surprising that Darwin was an agnostic, but he did not deal directly with the religious implications and theological consequences of the fact of evolution. No doubt, he himself was disturbed by the ramifications of evolution for Christianity. The power of science and reason had demolished the traditional beliefs concerning this universe, life on earth, and the place the human species occupies within dynamic nature. Neither this small planet nor the human animal on it could still be held to be absolutely unique within cosmic reality.

In summary, Darwin developed his theory of evolution as a result of the convergence of three important events: accepting Lyell’s geological perspective, reflecting on his exceptional experiences during the global voyage of HMS Beagle, and benefiting from Malthus’s insightful theory of population growth. It is to Darwin’s great credit that his analytic abilities were supplemented by a rational imagination. Through abduction, the creative interrelationship of facts and concepts, he was able to elevate his own methodology above a strictly empiricist approach to investigating the natural world in terms of the earth sciences. This open orientation of synthesis allowed him to bring about a conceptual revolution in terms of the biological evolution of all life on this planet.

There is a crucial distinction between evolution and interpretations of this process. Darwin was able to replace myopic opinions and naive superstitions with science and reason. For him, vitalism and theism were no longer needed to explain human existence in terms of organic evolution. As such, the theory of evolution has provoked philosophers and theologians alike to accept a dynamic interpretation of this universe and a new conception of the creation and destruction of life throughout organic history.

Darwin’s scientific writings make no appeal to a personal God to account for organic evolution or the emergence of our own species. Darwin was an agnostic in a cosmological context but an atheist within the evolutionary framework. We might wonder what his thoughts on religion and theology were when, as an aged naturalist, Darwin took those daily strolls down the Sandwalk behind his residence, Down House, in Kent, England. His reflections on scientific evidence must have caused him to doubt every aspect of theism, and perhaps in his later years, he was a silent atheist who kept his disbelief to himself, just as his own free-thinking father, Robert Waring Darwin, had kept his atheism from influencing the other members of the Darwin family.

It may be argued that Darwin himself demonstrated a failure of nerve in his own unwillingness to clearly state an atheistic position. Nevertheless, as an iconoclastic scientist and transitional naturalist, he paved the way for the pervasive materialism of modern times.

Consequences of Evolution

Although a shy and gentle apostate in science, Darwin had opened the door onto a universe in evolution. Of the countless millions of species that have inhabited this planet, most of them now extinct, only one life form has been able to philosophize on both its own existence and the natural environment: We may speak of Homo sapiens sapiens as this evolving universe conscious of itself. More and more, through science and technology, the human species is capable of directing its ongoing evolution as well as determining the future destiny of plant and animal forms on the earth and elsewhere. Today, we witness emerging teleology as a result of human intervention. This incredible power of control over life dictates that human beings make value judgments that could affect their adaptation, survival, enrichment, and fulfillment. What we may learn from evolution is that, as a species-conscious and evolution-aware form of life, humankind needs other plants, animals, and a suitable environment for its ongoing existence. And the inevitability of extinction is a brute fact for all life.

Clearly, Darwin had both intellectual and personal integrity; he was willing to change his scientific interpretation of nature as the integration of empirical evidence and rational concepts dictated. He exemplifies an open-minded and courageous naturalist whose commitment to organic evolution challenged both the engrained Aristotelian philosophy of fixed species and the Thomistic theology of divine causality.

In his autobiography, Darwin writes about his extraordinary global voyage on the HMS Beagle and subsequent productive life at Down House, despite chronic illness. Five chapters focus on the preparation, publication, and critical reviews of On the Origin of Species (1859), the naturalist’s major contribution to evolutionary thought. Interestingly, his wife Emma Wedgwood Darwin had deleted the references to God and Christianity from the posthumously published Autobiography. Not until 1958 did an unexpurgated version of this significant work appear in print.

In Chapter 3, Darwin presented his final thoughts on religion and theology. It is clear that this evolutionist and materialist was reticent to express his own beliefs. Even so, his personal thoughts neither verify nor falsify the evolved claims of religionists and theologians. It suffices that Darwin’s theory of evolution is strictly naturalistic, both in principle and intent.

References:

- Dennett, D. C. (1995). Darwin’s dangerous idea: Evolution and the meanings of life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Mayr, E. (1991). One long argument: Charles Darwin and the genesis of modern evolutionary thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moorhead, A. (1969). Darwin and the Beagle. New York: Harper & Row.

- Ridley, M.(Ed.). (1996). The Darwin reader (2nd ed.). New York: Norton.

- Weiner, J. (1995). The beak of the finch: A story of evolution in our time. New York: Vintage.